Explaining the First Folio (and the Final Shakespeare Mystery)

This is the post for which all authorship scholars have been waiting

As we have shown over the last few weeks, the simple solution to the mystery of Shakespeare’s plays is to recognize that, yes, Shakespeare’s name does indeed appear on the plays that he crafted, and no, no one was trying to give him false credit. It is just that the correct title pages are the ones that fronted the inferior staged adaptations that his companies actually performed and that were published during his lifetime. As we have discussed, these were the dramas his audiences and contemporaries believed he had written, these were the plays the title pages clearly indicate he had written, and, given his rather cloistered life devoted to the theater, it is only these plays that Shakespeare could have possibly written.

We can put this another way. The Hamlet, Henry V, Romeo and Juliet, etc., that we celebrate today were Shakespeare’s source-plays. They were written by Thomas North, and are the older, longer literary works that Shakespeare adapted. Shakespeare really wrote the shorter, staged adaptations, or “bad quartos,” of Hamlet, Henry V, and Romeo and Juliet, etc —theatrical revisions that were published while Shakespeare was alive with his name on the title pages. Shakespeare also worked on mediocre plays now deemed apocryphal—and, like the bad quartos, these plays were also attributed to him. So how did we end up getting this backwards?

I mean, if scholars know Shakespeare wrote adaptations of Hamlet, Henry V, and Romeo and Juliet—and know the bad quartos are indeed theatrical adaptations of Hamlet, Henry V, and Romeo and Juliet—and know Shakespeare’s company performed these swifter, less literary adaptations—and know these versions were published while he was alive with his name on their title pages, then how can there be any confusion over what he wrote?

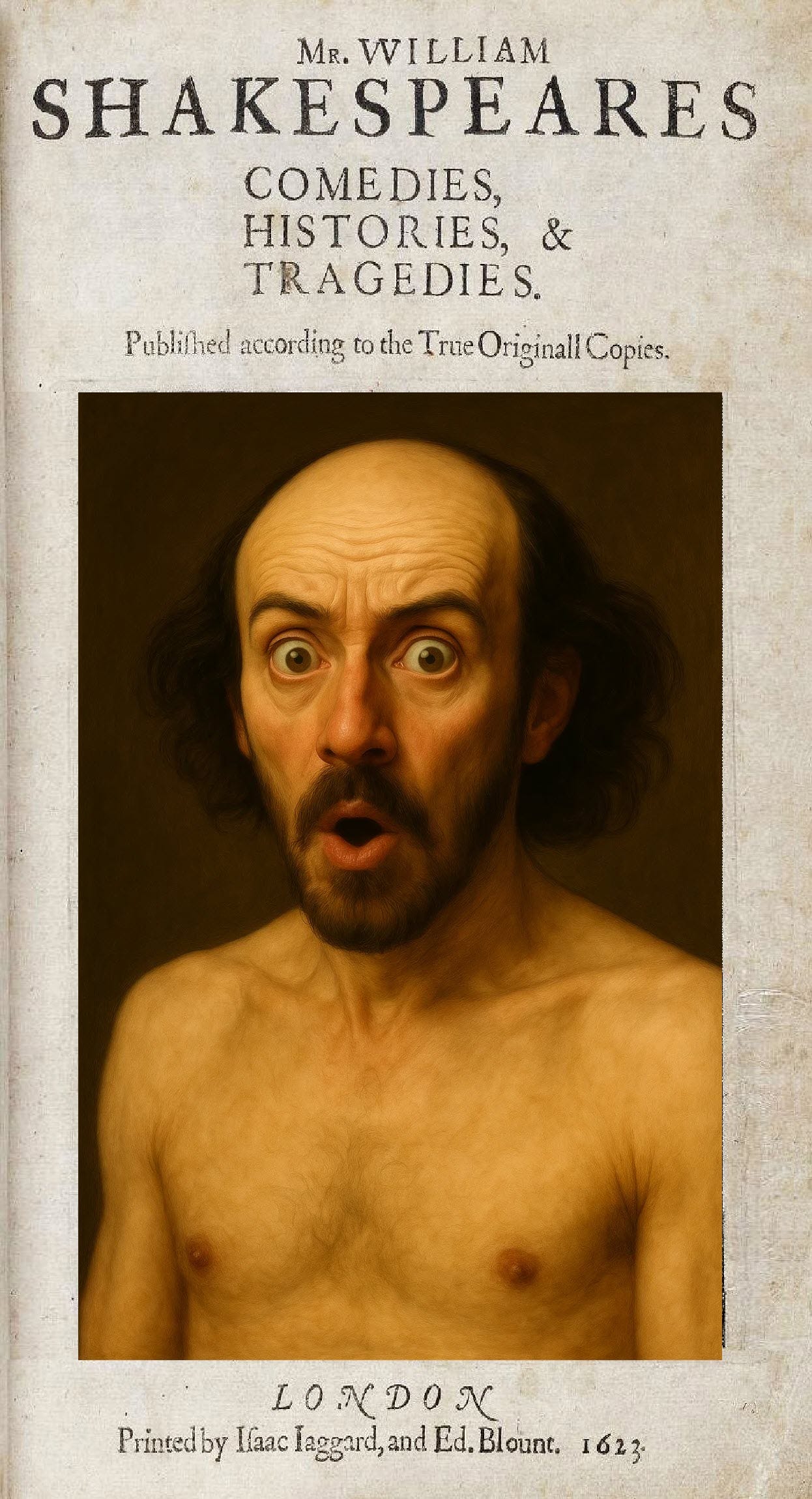

Short answer: Because for centuries scholars had taken for granted that a posthumously printed collection of Shakespearean plays known as the First Folio (1623) was the unimpeachable standard of authenticity—and have ignored essentially all other relevant documentation.

For example, below is a list of six categories of records from the 16th and 17th centuries that explicitly identify Shakespeare’s plays:

Title pages of Shakespeare’s quartos printed during his lifetime

The 1619 collection of Shakespeare’s plays (Pavier-Jaggard Quartos);

The First Folio (1623) and its reprint, the Second Folio (1632);

The Third (1664) and Fourth Folios (1685);

Bookseller’s catalogues;

What Shakespeare’s contemporaries believed he wrote.

As we shall see below, all of this documented evidence is consistent, mutually reinforcing, and perfectly explainable given the normal publishing practices of the era. It’s clear what Shakespeare really wrote. In contrast, Shakespeare scholars, all starting with the prior assumption that he penned the original masterpieces, must find reasons to reject the straightforward facts documented in five of these six categories. Specifically, the following list is what orthodox scholars accept as accurate—with a line crossing out everything that they have hypothesized was the product of deceit, conspiracy, and/or confusion:

Title pages of Shakespeare’s quartos printed during his lifetimeThe 1619 Collection of Shakespeare’s Plays (Pavier-Jaggard Quartos);The First Folio and its Reprint, the Second Folio;

The Third and Fourth Folios;Booksellers’ catalogues;What Shakespeare’s contemporaries believed he wrote.

Scholars have to ignore all other collections of Shakespeare’s works—like the 1619 Pavier-Jaggard collection and the Third and Fourth Folios—because they include the apocrypha. Moreover, they have to ignore what Shakespeare’s companies performed because they performed the inferior renditions known as the bad quartos. And they have to reject what many contemporaries claimed Shakespeare wrote and what booksellers’ catalogues listed. In contrast, the North view requires no schemes or fraud involving Shakespeare’s plays. Indeed, the North-view is the only non-conspiracy theory of Shakespeare authorship—and accepts the straightforward declarations of the title pages.

Still, all this begs the literary question of the millennium. How do we explain the First Folio? If Shakespeare’s first quartos accurately depict what he had written, then why wouldn’t the First Folio include those plays—as opposed to printing so many of North’s original, literary works?

What follows is the true story of exactly what happened in 1623, proved via a deep dive into the lives and records of everyone involved in the publications of the First and Second Folios. And, to be honest, the findings surprised me.

The 1623 Folio:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to All The Mysteries That Remain to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.