Frequently Asked Questions about Thomas North and William Shakespeare (Part 1)

Everyone agrees Shakespeare adapted anonymous old plays, and now we know who wrote them

The following helps answer some of the most common questions regarding William Shakespeare’s adaptation of North’s old plays. This post is adapted from Thomas North: The Original Author of Shakespeare’s Plays.

Q. Why wouldn’t North publish his plays when he first wrote them?

A. Because throughout North’s prime writing years—1550s to early 1590s, almost no one ever published plays. According to David McInnis and Matthew Steggle (in the introduction to their Lost Plays in Shakespeare’s England), only 543 plays currently survive out of approximately 3,000 performed in the commercial theaters between 1567 and 1642.[i] This is a survival rate of a little more than 18%. The lack of interest in publishing plays is the main reason so many of these plays are now lost. Moreover, these numbers include plays from the first half of the 17th-century, when plays became increasingly popular. The percentage of printed plays in the 16th-century is even lower. Philip Henslowe’s records confirm that nearly 90% of the plays that he produced between 1592 and 1603 are now lost.[ii] And the percentage of published plays in the decades during which North mostly wrote was even lower.

Finally, this percentage is for plays of the public theaters. But the first truly successful commercial theater would not be built until 1576. Prior to that, plays were mostly a privileged diversion. Noblemen, like the Earl of Leicester, funded the theater troupes, and they produced their plays before the queen or at private manors, universities, or the Inns of Court. Naturally, if publishers often avoided the plays of the commercial stage, they would have had even less desire to produce scripts of plays about which the general public was largely ignorant. For example, Leicester’s theater troupe performed plays steadily for nearly 30 years (1559–88)—in London, in the suburbs, in tours to country estates and universities, even in Europe. Yet, as Terence Schoone-Jongen writes, “little information about Leicester’s repertory survives.”[iii] Who was writing all the plays that they were performing for those decades? Scholars have ventured a few educated guesses on who may have written a few of them, and, importantly, newly uncovered records now confirm that North was one of the dramatists for Leicester’s Men (see prior Substack: “Thomas North: Playwright,” and June Schlueter’s and my comment on it in The Times Literary Supplement. )

Another confounding factor is that many of the plays printed during the Shakespeare era were published anonymously. Thus, our knowledge of Elizabethan playwrights often derives not from published title-pages but from the work of literary archaeologists who, through historical research and linguistic analyses, have uncovered their identity and reconstructed their oeuvres. Thomas Kyd, author of The Spanish Tragedy (~1588), for example, was mostly unknown to literary scholars for centuries after his death. Prior to that, few had ever come across his name or knew the authorship of his plays. As recounted in the classic 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica:

Kyd remained until the last decade of the 19th century in what appeared likely to be impenetrable obscurity. Even his name was forgotten until Thomas Hawkins about 1773 discovered it in connexion with The Spanish Tragedy in Thomas Heywood’s Apologie for Actors. But by the industry of English and German scholars a great deal of light has since been thrown on his life and writings.[iv]

Thomas Middleton[v] and Anthony Munday[vi] have similar stories. Both are early seventeenth-century playwrights whose dramatic contributions had to be identified by later scholars. North is no different in this regard. He is just the latest playwright to be discovered and saved from obscurity through a posthumous reconstruction of his canon.

Q. Why wouldn’t North want money and credit for these plays?

A. He did get money and credit for them. But his first rewards came years earlier when he was writing plays for the Earl of Leicester’s theater troupe or when they were first produced before Queen Elizabeth or at a nobleman’s house. That is when he first received his payments and heard the applause. But as newspapers and literary magazines did not exist at the time, no one recorded these accolades. Moreover, the scant Revels account transactions only provided limited information about the plays performed for the queen—and almost never mentioned the playwright. Indeed, as noted above, one of the few records we have of a playwright getting paid for a Leicester’s Men’s play was a payment to Thomas North in June 1580, for a play at court. North also almost certainly received payment for his plays from Shakespeare, but, unlike Philip Henslowe, neither Shakespeare nor anyone else with the Lord Chamberlain’s or King’s Men kept theatrical records that have survived.

Importantly, Shakespeare also did not even publish the majority of his plays. And if it were not for the fortuitous publication of a collection of his works seven years after he died—the First Folio—we would have lost Antony and Cleopatra, Macbeth, Twelfth Night, The Winter’s Tale, Julius Caesar, The Tempest, As You Like It and many other plays. Indeed, in most cases, we would have never known these plays had even existed. Does this mean Shakespeare did not want money or credit for these plays? Of course not. He did get money and credit for these plays when he produced them—but evidence for that was never recorded.

Q. Wouldn’t Shakespeare’s contemporaries have mentioned or even complained that he was getting too much credit for old plays?

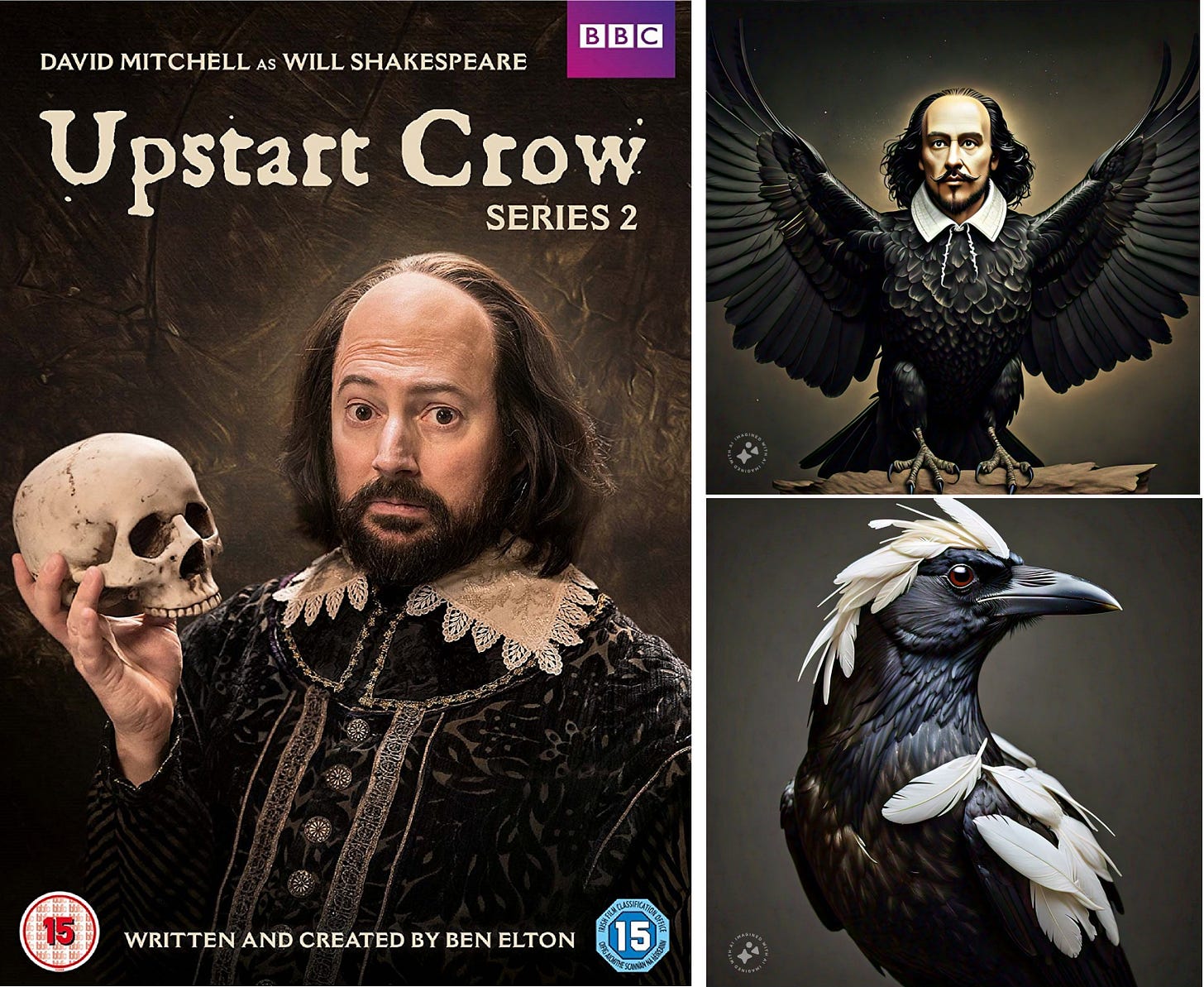

A. They did! As is conventional, others did mention (even complain about) Shakespeare’s frequent use of old plays. An earlier Substack— The Absolutely True, Indisputable, and Definitive History of the Shakespeare-Authorship Controversy—examines four comments from the 16th and 17th centuries, plus four more that appeared in the 18th and early 19th centuries, all referring to Shakespeare as an adapter of earlier plays. This includes the first reference to him as a playwright in Groatsworth of Wit (1592), which derides him as an “upstart crow, beautified” with the feathers of other writers. It also includes two poems about Shakespeare by Ben Jonson: “On Poet Ape” and “Ode to Himself,” both of which describe his penchant of purchasing and reworking old plays.

Even in the decades after Shakespeare had died, writers would still make similar comments. In 1687, Edward Ravenscroft crafted an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, stating in a prefatory note that he had “been told by some anciently conversant with the stage, that it [Titus Andronicus] was not originally [Shakespeare’s] … and he only gave some master-touches to one or two of the principal parts or characters.”[viii] Likewise, in 1728, a Captain Goulding recorded an old rumor that had originally come from an “intimate acquaintance” of Shakespeare’s that he had kept a hired historian in his employ who had written all the plays that he then adapted. Even the first renowned Shakespeare scholars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries continued to refer to him as an adapter of old plays. As literary biographer Scott Astley Dunham wrote in 1837: “that extraordinary man was satisfied with reconstructing the pieces which others had composed; he was not the author, but the adapter of them to the stage.”[ix]

Of course, we do not find similar comments regarding any other renowned author. We do not come across any fellow writers decrying Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Middleton, or Ben Jonson as play-recyclers who got too much credit for works of other authors. Indeed, we do not see any later playwright saying that he or she heard from an old theatrical insider that A Long Day’s Journey into Night was not originally Eugene O’Neill’s or A Doll’s House was not Henrik Ibsen’s. The reason we keep finding this same claim repeated about Shakespeare is that it was true.

Upcoming questions that will be answered in Part 2:

Q. Is it really feasible that Shakespeare would get so much acclaim and full authorial credit for plays that were very close adaptations of North’s writings?

Q. Why didn’t Shakespeare adapt anyone else’s plays and get credit for those? (He did)

Q. Well, aren’t all the source plays lost? And if so, what actually can be said about lost plays?

Q. Why is North’s identity only being discovered now?

[i] David McInnis and Matthew Steggle, “Introduction: Nothing Will Come of Nothing? Or, What Can we Learn from Plays that Don’t Exist?”, Lost Plays in Shakespeare’s England, ed. David McInnis and Matthew Steggle (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 1. See also Dennis McCarthy and June Schlueter, Thomas North’s 1555 Travel Journal: From Italy to Shakespeare (Vancouver: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2021), 167.

[ii] Neil Carson, A Companion to Henslowe’s Diary, 82–4. See also Dennis McCarthy and June Schlueter, Thomas North’s 1555 Travel Journal, 167.

[iii] Terence Schoone-Jongen, Shakespeare’s Companies: William Shakespeare’s Early Career and the Acting Companies, 1577–1594 (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008), 175.

[iv] “Kyd, Thomas (1558–1594),” The Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. (New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company, 1911), 15:958.

[v] In the early twenty-first century, a similar effort was made to reconstruct the canon of Thomas Middleton, who also had remained little studied until the nineteenth-century. Researchers had not been sure about the extent of his writings until the last few years, when stylistic analyses indicated that he had helped Shakespeare adapt both Measure for Measure and Macbeth. As Gary Taylor writes about the once forgotten playwright: “The first attempt to put him back together again was made by the Rev Alexander Dyce in 1840. Dyce’s edition immediately established Middleton as a major playwright, but it also attributed to him some mediocre work by other people, omitted some of his best work, and seriously distorted his biography…” Gary Taylor, “The Orphan Playwright,” The Guardian Online, www.theguardian.com/books/2007/nov/17/classics.theatre

[vi] Anthony Munday was another writer who had to be saved from anonymity by modern researchers. Quoting I. A. Shapiro: “If we may trust the scanty contemporary references to him, Anthony Mundy was one of the most prolific and successful of Elizabethan dramatists; in Francis Meres’s opinion he was also one of the best. Yet very few of his plays are known to be extant, and even those have been identified as his only in modern times.” I. A. Shapiro, “Shakespeare and Mundy,” Shakespeare Survey 14 (1961): 25–33; 25.

[vii] Walter Raleigh, Shakespeare (London: Macmillan, 1907), 70–1.

[viii] Edward Ravenscroft, Titus Andronicus, or, The Rape of Lavinia acted at the Theatre Royall: A Tragedy, alter’d from Mr. Shakespears works (London: J. B. for Joseph Hindmarsh, 1687), sig. A2.

[ix] Samuel Astley Dunham, The Cabinet Cyclopaedia, Conducted by the Rev. Dionysius Lardner, LL.D., etc.: Eminent Literary and Scientific Men of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 2 (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Greene and Longmans; and John Taylor, 1837), 35.

Have you heard of Samuel Crowell's "William Fortyhands"? He argues that there was not a single author of Shakespeare's plays, but instead Shakespeare was a producer who hired people like Robert Greene to write plays, then had them rewritten to appeal more to audiences (like Samuel Pepys', whose favorite parts of Shakespeare's plays are things absent from published versions now). https://www.ninebandedbooks.com/shop/book/william-fortyhands-disintegration-and-reinvention-of-the-shakespeare-canon/

Here’s my issue with the court plays theory. When Marlowe debuted Tamburlaine circa 1587, it was greeted as an innovation. Marlowe himself announced as much in his opening lines: "From jigging veins of rhyming mother wits, And such conceits as clownage keeps in pay, We'll lead you to the stately tent of war." His fluent blank verse avoided the end-stopped lines and singsong accentuations of earlier poetry, his characters were larger than life, and their oratory was (sometimes tediously) grandiose. The play was a sensation and was quickly imitated by inferior playwrights like Robert Greene.

If Shakespeare had been writing court plays for more than a decade earlier, in anything like the form in which we know them, then he also had mastered this freer form of blank verse coupled to large themes and high-flown rhetoric, in which case Marlowe wasn’t doing anything new. At the time, however, Kit and his contemporaries clearly believed that he had ushered in a whole new style. This suggests to me that the court plays were comparatively primitive works like Gorboduc, and not likely to resemble the Shakespearean canon.

It is possible to argue that the court plays were always more sophisticated, and that Marlowe's innovation lay only in bringing this level of quality to the public stage. But we don’t have any examples of plays with Marlowe's style of blank verse that are unambiguously pre-1587, so this supposition is unsupported by evidence. And the contemporary reaction to Tamburlaine, even among other poets and playwrights, suggests that no one had seen anything like it before.