Antisemitism and Hamlet

I think October 7th is a fitting day to repost this article on a truly fascinating survivor. Some day I will post more on the scourge of antisemitism—and why this ancient plague still thrives among the crude, the stupid, and the savage.

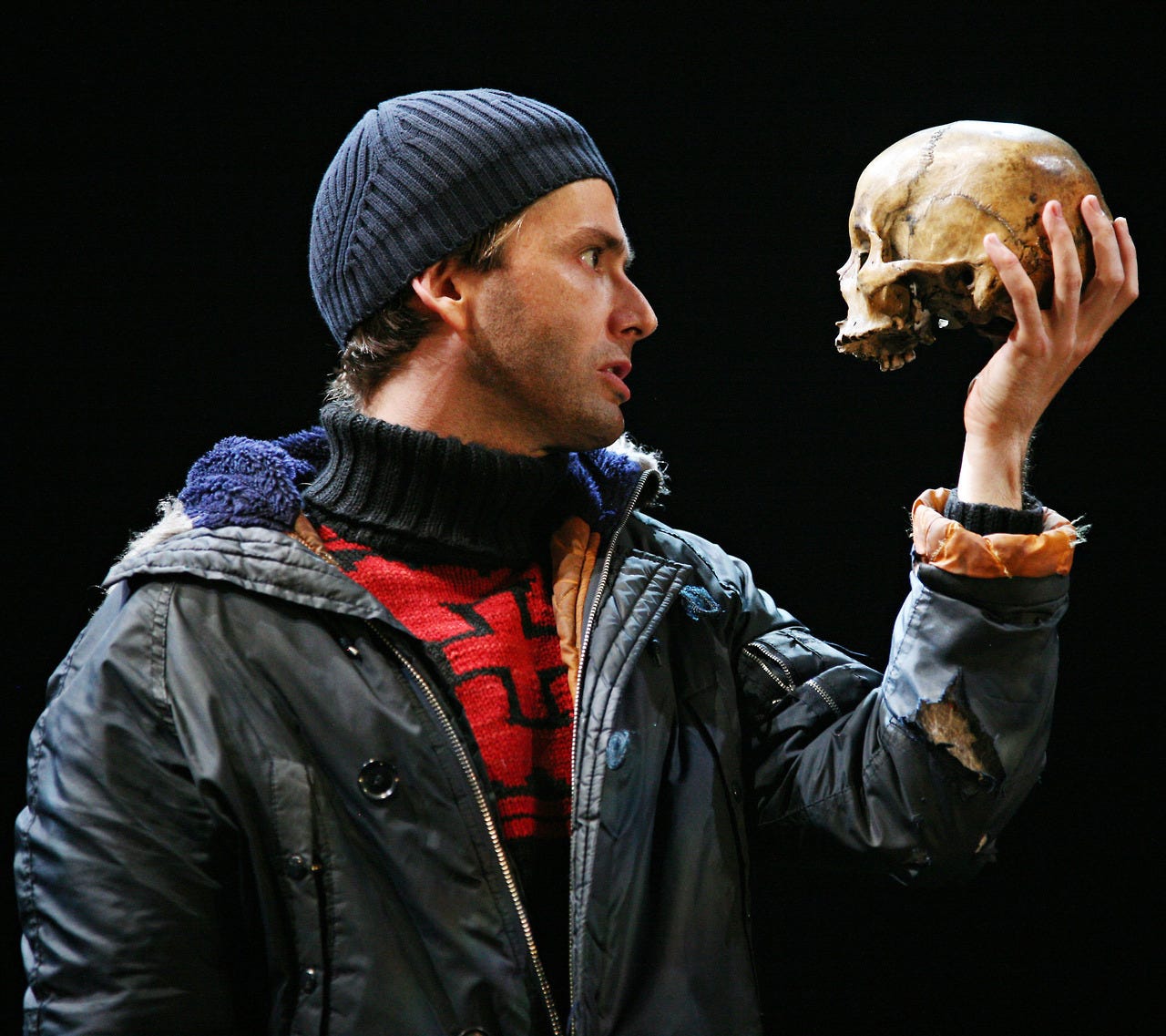

In 2008, the English actor David Tennant, well-known to millions for playing Dr. Who, held up a skull, stared at it for a moment, eye to eye socket, and then said: “Alas, Poor Yorick. I knew him, Horatio.”

Tennant, of course, was playing Hamlet in the iconic graveyard scene for the Royal Shakespeare Company. Yorick had been the King’s jester when Hamlet was a boy, a beloved, full-time live-in clown who entertained the royal family with jokes, word-play, and dances. He was a warm and special part of Hamlet’s childhood and now the Prince was holding Yorick’s head with the flesh, eyes, and brain all rotted away. Hamlet can barely stomach the grotesque significance of it, and he reminisces about him to his friend Horatio:

“A fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy. He hath borne me on his back a thousand times. And now how abhorred in my imagination it is! My gorge rises at it.”

The scene is so prominent that, in many productions, one can sense the audience lean forward as it begins. But in David Tennant’s performance, the graveyard speech drew an especially heightened attentiveness. Rumor had gotten out that Tennant did not hold a plastic prop but a real human skull—a rumor the actor would later confirm was true.

Andre Tchaikowsky, a Polish composer and pianist, had died of colon cancer in 1982 and willed his skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company. He wanted it to be used in this scene, and some twenty-five years later, after getting permission from the “Human Tissue Authority,” Tennant granted Andre this wish.

Tchaikowski was born to a prosperous, educated, musical, and matriarchal family. His maternal grandmother, Celina Sandler, was a wealthy, go-getting, cosmetics entrepreneur, and his mother, Felicia, could speak five languages and was a talented singer and pianist. Andre inherited their abilities. Before he had turned four, he could read in three languages—German, Polish, and Russian—and then he learned to play the piano that following year.

Unfortunately, as we find so frequently throughout history, time and place are everything. So while it may be difficult to imagine a more promising future for young Andre, all of it was tragically offset by the cataclysmic setting of his birth: Andre was born in 1935, his family was Jewish, and they lived in Warsaw.

At that time, a forceful populist was slowly gathering power in the country directly to Poland’s west. He promised a return to former glory and stoked resentments against foreigners and elites—and most especially against the one group of people so often targeted as examples of both. On September 1st, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland, the Jewish population of Warsaw was 335,000. In 1940, the Nazis forced the Jews of the Polish capital into a small neighborhood of apartment buildings, 1.3 square miles in size. Then surrounded it with brick walls, barbed wire, and armed guards.

This was the Warsaw Ghetto. Jews were brought in from nearby towns too, swelling the population of the Ghetto to 400,000, which worked out to an average of more than seven persons per room. In 1942, the freight trains started bringing the Jewish residents of the Ghetto to the Treblinka death camp. Three years later, by the end of the war in 1945, the Jewish population of Warsaw had dropped to 11,500.

Another Jewish pianist and composer also lived in Warsaw at this time. Wladysław Szpilman, 24 years Andre’s senior, managed to survive the German occupation through intelligence, perseverance, and the good fortune to run into the right, sympathetic people at the right time. This includes Wilhelm Hosenfeld, a German captain and member of the Nazi Party since 1935. Hosenfeld was resistant to the dark urgings of his peers and retained his sense of humanity. He helped hide and feed Poles and Jews during his time at Warsaw, including the young composer. The film “The Pianist” recounts Szpilman’s agonizing efforts to outlast the German occupation—and his fortuitous encounter with Hosenfeld.

Young Andre survived through the sheer force of will of his grandmother. Celina had managed to escape the Ghetto by pretending to be a Christian and moving to a house just outside the wall. But through trades and bribes, she was able to visit the Ghetto daily and bring food and supplies to her family. In the summer of 1942, when the deportations to Treblinka began, Celina smuggled her grandson out of the neighborhood-prison. She dyed his hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes blonde, dressed him as a girl, and walked him right out of the Ghetto in front of the police. His mother Felicia believed the two had a better chance without her, and stayed behind with her second husband. Andre’s mother and step-father would be deported and murdered in the chambers of Treblinka before summer was out.

This is when Andre got his name. He was born Robert Andrzej Krauthammer, but Celina knew that was too Jewish for 1942 Warsaw. When she procured false documents for him she had him use his middle name and changed his last name to Czajkowski, after one of her factory workers. It is merely a coincidence that his name ended up so closely resembling that of a famous Russian composer.

Celina then secured hiding places for Andre, sometimes without her, for the next three years by bribing families in and around Warsaw. At one stop-over at the home of an elderly and infirm mother and her daughter, Monica, Andre had to spend most of the time alone in the darkness of Monica’s lice-filled armoire, with nothing but a chamber-pot in one corner. Monica at that time was unmarried and pregnant, and she despised the guest with whom she had to share her bedroom, even if he was almost always kept locked up, out of sight, in her wardrobe. When Celina stopped by to negotiate payment for a longer stay, Monica started loudly ranting that she wanted Andre out of the house. Celina protested that it was daytime, and there was nowhere to take him, but Monica yelled that she did not care, and told her to give Andre over to the Gestapo for a reward. When Celina tried to calm her, Monica got louder and threatened to go to the Gestapo herself. Finally, Andre’s fierce grandmother told her that was fine. The Gestapo was merely two streets away, but to remember that they would certainly have questions for Andre about where he had been staying all this time. She continued:

The penalty for hiding a Jew is the same as for being one. And you know what that is, don't you. You can see them hanging from the lampposts all over town. Sometimes they are hanging upside down. Which takes much longer. You wouldn't look your best that way.1

Celina remained calm throughout the discussion: "Whatever happens to the boy shall happen to you Miss Monica. I will see to it that it does.” He was allowed to stay.

In the dark of the wardrobe, Andre would practice memorizing the Lord’s Prayer and at three different times had to endure crude operations trying to reverse his circumcision. This was how Andre spent his life from ages seven to ten, and its stressful effects would remain with him for all his life. Andre matured into an erratic, witty, and temperamental genius. After the war, he studied to become a concert pianist in Paris and Warsaw, and soon he was composing original works. As he also loved Shakespeare, he based some of his music on his plays and poetry, including The Seven Sonnets of Shakespeare for piano and voice, the song cycle Ariel based on the spirit from The Tempest, and an opera on The Merchant of Venice. Andre worked on the opera for the last 14 years of his life but died before he could see it produced. It is certainly understandable that for Tchaikowski’s most important and time-consuming project, indeed his swan-song, he chose to recraft a play that dealt so directly with antisemitism, with a main character who was a prosperous Jewish merchant who lived in a Jewish ghetto in a wealthy city controlled by Christians. In 2013, the opera finally received its world premiere to positive reviews at the Bergenz Festival in Austria.

Andre also saw a performance of Hamlet by the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), but according to his friend and agent Terry Harrison, he was dissatisfied with the graveyard scene because of the fake prop used for Yorick:

"He hated the way it was done. When he saw it with the RSC, he (Andre) said 'I am going to leave my skull to the RSC, they really should have a proper skull. It doesn't work with the plastic thing they have'. And then we looked at his will, and there it was."

Andre would have been pleased to know that Tennant used it and would have understood the relevance. As the director Greg Doran said, “You can't hold a real human skull in your hand and not be moved by the realisation that your own skull sits just beneath your skin, that you will be reduced to that at some stage.”2 This was the main point of the scene.

Prior to the Yorick speech, Hamlet wondered about the former identities of the other skulls that the gravedigger knocked about with his shovel, the richness and variety of the lives that had all been brought to the same humble place and state: “That skull had a tongue in it, and could sing once,” says Hamlet as he watches the gravedigger carelessly toss it to the ground. Other skulls, observed the Prince, might be that of a politician or a courtier or a lawyer.

And in a 2008 performance in Stratford, one of the skulls was of a concert pianist and composer who had led a truly remarkable life.

From Chapter One, “Saint Monika’s Wardrobe,” From Andrzej Czajkowski’s manuscript “Autobiografia”; https://zapispamieci.pl/en/andrzej-czajkowski/

“David Tennant's Hamlet featured real human skull all along, admits RSC,” The Telegraph, 25 November 2009

Thank you, Dennis, for a truly fascinating article.

Dennis, the North/Greene/Shakespeare relationship is really something to explore. Did North supply material to Greene for Pandosto in 1588, but then Shakespeare came along and paid more to North, Greene lost out and retaliated 4 years later in Groats-Worth of Wit? Why did Greene attack Shakespeare for using North's material without attribution if Greene himself did the same with Pandosto (as you propose)?