Debating Philip Womack (Or the Orthodox Conspiracy Theories Used to Prop Up Shakespeare's Reputation)

The challenge is straightforward.

Other than Shakespeare, name any playwright in the Shakespeare-era who had a play deliberately and falsely attributed to him on a title page while he was alive.

And, failing that, how about this:

Name any single work in all of English publishing history that was deliberately, exclusively, and falsely foisted upon another living author by printers, publishers, etc., by placing their name on the title page when they had nothing to do with that work. Name one. Ever.

Now, at first glance, one might suspect that this challenge1 had been put forth by a Shakespeare scholar and demanded of some heretic who was trying to credit some other writer for his masterpieces. After all, aren’t anti-Stratfordians the only ones who claim Shakespeare didn’t write a large number of plays explicitly attributed to him?

Nope.

As we shall see, just like the Shakespeare-doubters they deride, orthodox scholars also contend Shakespeare didn’t write a large group of plays—12 of them—that carried his name on their title pages. Remarkably, these supposedly-fraudulent works compose the majority of plays attributed to Shakespeare via title page during his lifetime and up until 1621. In fact, the challenge quoted above is the one I gave to acclaimed children’s author, knowledgeable classicist, and enthusiastic defender of Shakespeare’s reputation, Philip Womack. Womack, a Shakespeare expert, is aggressively anti-anti-Stratfordian and has posted well-crafted Substack articles attacking the more outlandish ideas of the “Shakespeare-deniers,” as he calls them. He has also previously gotten into debates with

-contributor and distinguished Marlovian literatus.I first came across Philip’s name in the comments section to my post: “Shakespeare Didn't Write the Masterpieces; He Wrote the Plays His Company Performed: the Bad Quartos.” He was challenging a few of my claims, and, naturally, I instantly invited him to discuss those issues on a live Zoom/Podcast.

has graciously offered to host such a debate between me and anyone serious who wants to challenge any aspect of the North theory, but, of course, we have never found anyone willing to step into the ring. Philip, likewise, quickly demurred. I believe that’s a wise decision on his part. As I have shown and will discuss below, all the documents—the title pages, the insider comments, etc.—could not be more clear about what Shakespeare wrote—and what he didn’t. Shakespeare wrote lesser, abridged stage adaptations of an elder genius’s works. And we also have now confirmed the identity of that elder genius—finding numerous documents that prove that earlier playwright was Thomas North:As the Substack-article above details, my co-author, June Schlueter, and I have passed peer review confirming that Thomas North did indeed write the original versions of Titus Andronicus, Henry VIII, and The Winter’s Tale. We have also demonstrated that the original author of the Shakespeare canon borrowed extensively from everything North ever wrote—including unpublished, handwritten manuscripts like his travel-journal. The sheer volume of North’s lines and passages that we have found in the canon makes it clear that no one in history has ever borrowed more from an earlier writer than Shakespeare has from North—and it is not even close. More, investigative journalist and New York Times best-selling author, Michael Blanding has investigated our claims, written a book on the subject and joined us as a research partner. It is Blanding who found North’s handwritten notes in the margins of a family history book, and it turns out they comprise the outline to Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. The post above includes summaries of still other smoking guns. There is just no reasonable way to challenge any of this—which is one of the reasons no one—and especially not Philip—will ever debate me on this live.

Bad Quartos and Apocryphal Plays

The post to which Philip was responding and, part of our debate, was over the authorship of Shakespeare’s “bad quartos” and “apocryphal plays”—plays that were printed while Shakespeare was alive, performed by his theater companies, and were printed with his name or initials on the title pages.

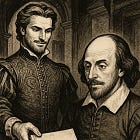

The bad (or first) quartos are inferior, shortened, more action-packed staged adaptations of the longer more literary versions of the plays. The pic below includes the first three lines of this first (or bad) quarto’s rendition of Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” speech—an amateurish and brief paraphrase of the more well-known soliloquy. This is a perfect example of how Shakespeare adapted North’s original plays.

Shakespeare’s apocryphal plays are works like Thomas Lord Cromwell, The London Prodigal, A Yorkshire Tragedy that were attributed to Shakespeare on their title pages while he was alive and that 17th-century editors, playgoers, and readers truly believed he had written. But scholars today find them so differently styled and so lacking in “Shakespearean” qualities that they have now removed them from the official canon.

Now, in my view, the reason Shakespeare’s name was on the title pages of all these plays is that, well, Shakespeare wrote them. Or, at least, he adapted them. In other words, it was Shakespeare who wrote the bad quartos, all of which were the first versions of the plays ever published and the ones that Shakespeare’s theater companies performed, and it was North who wrote the longer masterpieces upon which those inferior adaptations were based. Likewise, the reason the allegedly apocryphal plays lack signature “Shakespearean” features is that they weren’t based on an original North play. So they include none of his plotting, characters, passages, or phrases. Since they lack his extraordinary style, these works are now considered apocryphal — no matter what their title pages state.

But how do conventional scholars and knowledgable Shakespeare enthusiasts like Philip explain the origin of the bad quartos and apocryphal plays? Well, they hypothesize various, behind-the-scenes schemes of fraud that began in 1594, continued to 1619, and fooled the world about what Shakespeare had really written for more than a century.

Explanation for the “bad quartos”: Conventional scholars blame the lesser adaptations on a system of conspiracies, occurring over decades. Supposedly, various groups of unknown anonymous actors working within the Stratford dramatist’s theater companies rewrote these plays, perhaps from memory, and then secretly sold them to corrupt publishers and printers who placed Shakespeare’s name on the title pages and printed them without authority.

Explanation for the “apocryphal plays”: Conventional scholars assume that printers and publishers pirated these plays. Specifically, they suppose the printers and publishers somehow obtained them from one or more of Shakespeare’s fellow actors (as the apocryphal plays were all performed by Shakespeare’s theater companies) and then published them without authority, falsely placing Shakespeare’s name on the title pages to fool prospective readers into thinking Shakespeare wrote them.

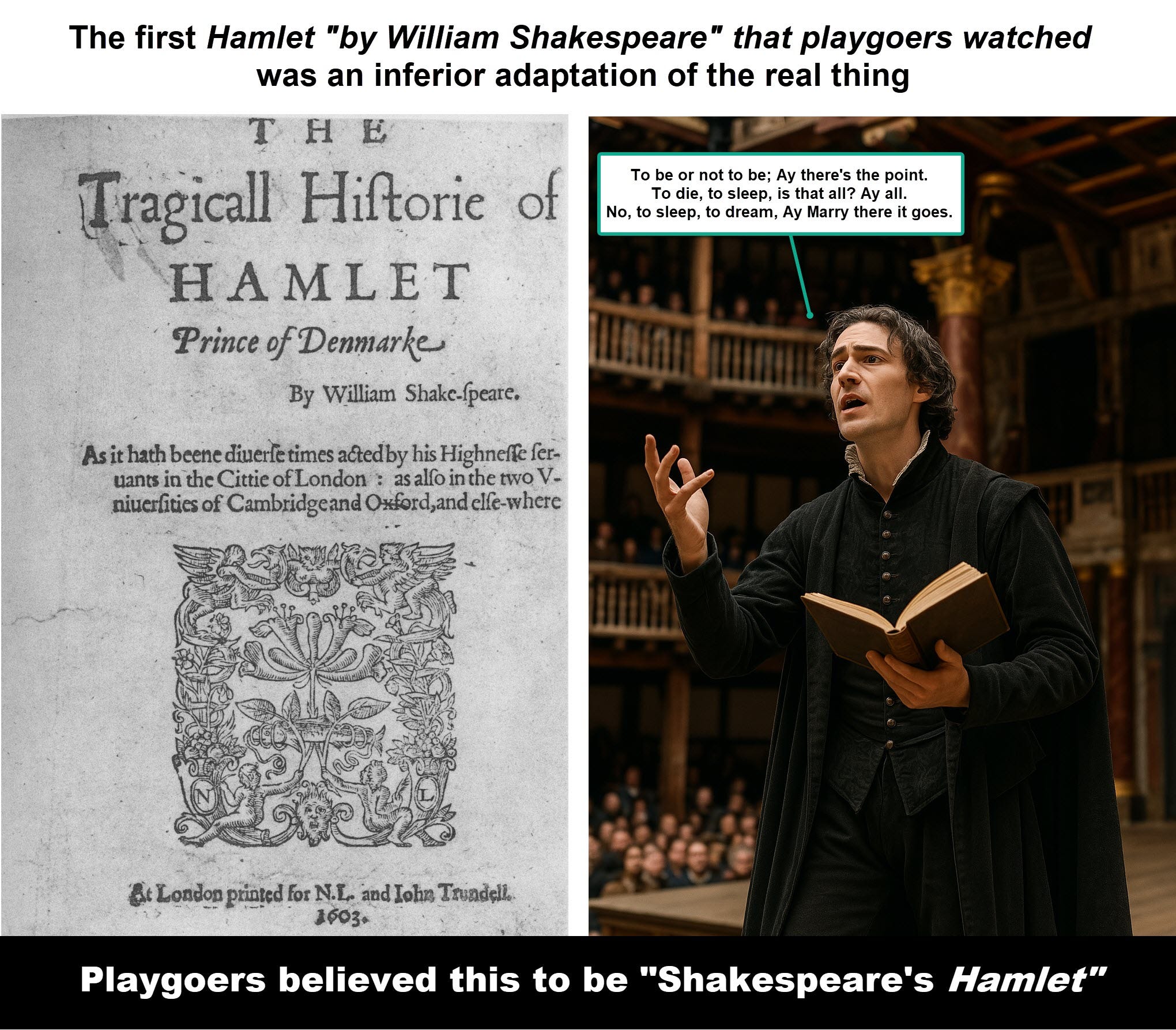

So persistent were these supposed schemes to defraud the public with poor adaptations and misuse of his name, that conventional scholars now believe that by 1621, Shakespeare’s name appeared more frequently on corrupt plays than genuine ones. The figure below lists every “Shakespeare” title page printed by 1621—and the statement in the purple box “These are Shakespeare’s Adaptations” reflects my view on the subject:

How can scholars like Philip Womack deny there’s a Shakespeare authorship question when they, themselves, deny his authorship for a dozen plays "written by William Shakespeare”?

There is simply no intelligible reason to doubt the veracity of all these "Shakespeare" title pages, and it is incredible to suppose that everyone involved in the publication of these plays—the fourteen different people listed in the shaded cells of the printer/publisher column above—was taking such a professional or even criminal risk by pirating plays and publishing claims that were easily proved false. Other than tradition and reverence for authority, what reason is there to believe such a thing?

In our debate, Philip Womack pushed the orthodox view above that apocryphal plays and bad quartos were all the result of some form of piracy. And I responded with something like the following:

Can you not tell how anti-Strafordian you sound here? You think the majority of plays attributed to William Shakespeare while he was alive and up till 1621 are fraudulent and the result of corruption (this is counting all apocryphal plays and bad quartos) despite the fact that:

Shakespeare never complained about his name falsely being used.

Shakespeare and company, who performed all these plays, never complained about their illicit procurement and unauthorized publication.

No one else ever mentioned it at the time or for decades afterward.

The real authors of the apocryphal plays never demanded proper credit.

None of the dozens of printers or publishers were ever punished for it.

These nefarious printers and publishers ended up pulling off a ruse that fooled the world for a century—as scholars, editors, etc. were still referring to "Yorkshire Tragedy" and "London Prodigal" as Shakespeare's into the 18th century.

There’s no rational reason to doubt Shakespeare’s authorship of these plays as no one at the time—or for even a century afterward—ever doubted it either. The truth is there was no wide-ranging plot to give Shakespeare false credit for The Merchant of Venice and Much Ado About Nothing as many anti-Stratfordians would believe, and there was no plot to give him false credit for True Tragedy, A Yorkshire Tragedy, Locrine, London Prodigal, Hamlet Q1, etc, as orthodox scholars and Shakespeare enthusiasts like Philip would believe. These were the works attributed to Shakespeare during his lifetime; these were the works that contemporaries were referring to when they wrote about Shakespeare’s plays; these were the works that Shakespeare’s acting companies performed, and these were the works that William Shakespeare of Stratford directed, abridged, revised, organized, augmented, and hired coauthors to help craft.

More on the Debate

As indicated above, I also stressed to Philip that no other playwright of the Shakespeare era was similarly victimized. In fact, no other living writer in all of English history had a similar misattribution occur to him just once—let alone twelve times! That is, there is no known case in history in which an English printer or publisher has ever purposefully misattributed a single work (like a play, essay, or novel) to a single, living author whom they knew had nothing to do with the work. Why is that? Well, because the printer and publisher would know that the living author whose name was being used would complain—and so too would the wronged author whose work was stolen and credited to someone else. In fact, as I showed in the debate, there may not be an indisputable example of such a misattribution occurring to a dead author either.2

Trying to meet the challenge, Philip gave the example of the early 20th-century, French writer, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette, whose first four novels were published under her cruel and domineering husband’s name. But as I responded, this fails the request in three ways: 1) It was the husband who took credit for the works, so the authorship wasn't foisted upon him by corrupt printers/publishers. 2) The husband, an editor and writer, was involved to some degree in the crafting of the works (though there's dispute about how much). 3) This non-example is from France. What is more, the example of Colette provides a much closer approximation of the anti-Stratfordian view—as it verges on the use of an allonym, with both writer and credit-stealer agreeing to the deal.

In any case, the reason Philip could not find such an example is that it has never occurred. And it didn’t miraculously occur a dozen times to Shakespeare either.

To conclude, we now know that Shakespeare penned lesser, collaborative works and inferior stage-renditions of literary masterpieces because that is what all documentation—all relevant title pages printed while he was alive and within a few years of his death—explicitly declared. Moreover, that is what all his fellow writers knew to be the case, with Robert Greene and Ben Jonson even deriding Shakespeare’s method of close adaptation as plagiarism. Thus, one of the main goals of this Substack is to prove that all the Shakespeare-era documentation is correct; that there were no devious, behind-the-scenes plots; that all the recorded observations and comments about the Stratford dramatist were factual; that large groups of playwrights, printers, and publishers were not concocting wide-ranging, multi-decade schemes meant to fool future generations of researchers. Incredibly, and despite the significant amount of controversy this view ignites, we are merely urging readers, again and again, to accept all the documentation at face value, to just believe their eyes.

The challenge refers to single works—and so excludes collections, especially of poems. Frequently, printers and publishers would pad collections of an author’s work with extraneous material so that not everything in a collection was necessarily by the writer on the title page. This is, of course, a very different thing than X writing “The London Prodigal”—but printers and publishers deliberately attributing it to Y.

One likely example of a work being falsely attributed to a dead author is Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit (1592), attributed to the recently deceased Robert Greene. Conventional scholars have put forth strong arguments that Thomas Nashe and Henry Chettle wrote most of the pamphlet—combining it with an unfinished work of Greene and then giving him full credit because of its controversial nature. But in this case it wasn’t a corrupt publisher, but the authors of the work themselves who assigned it to Greene. Moreover, there were immediate, contemporaneous accusations that Chettle and Nashe were indeed the authors of the pamphlet. [Also, a careful study of Lukas Erne’s examples in the 17th century of some older works being falsely attributed to dead authors are likely all errors.]

To be fair, the official explanation of the bad quartos is that someone among the staff or audience wrote the staged plays down and had them published, attributed correctly to Shakespeare. The official explanation of apocryphal plays varies, from Shakespeare publishing plays by other authors under his name (perhaps similar to the sonnets and poems) to others using Shakespeare's name if Shakespeare was a pseudonym who couldn't complain. All of these are more or less plausible explanations within their respective theoretical frameworks, but I agree that your explanation is the most plausible one.

More importantly, we don't know if Shakespeare "penned" any plays himself because no handwritten manuscript or fragment survived, apparently. We only really know that "his" name appears on title pages of plays not originally written by him.

Though not an exact answer to your challenge, there are works that were falsely attributed to persons who never wrote them, with the connivance (in some cases) of the people who put up the money to bring the works to the public. I’m thinking of the various TV and movie scripts that were credited to front men during the McCarthy era, when the actual scriptwriters were blacklisted. Some of the producers were duped by the front men, but others seem to have known who really wrote the script — or at least that the real writer, whoever he was, was a seasoned pro who (for reasons best left unexplored) no longer used his real name.

Many anti-Stratfordians rely on this analogy to suggest how an aristocrat might have been protected from "the stigma of print" through employment of a front man. Presumably the front (Mr. Shaksper) would have offered his services to other writers who also needed to preserve their anonymity — hence the inclusion of London Prodigal etc. in his listed works.

I’m not saying this is true. Your analysis is probably the right one. But the McCarthy parallel does show that some publishers/producers could conspire to conceal the true writer's identity.

Of course there are also many examples of uncredited ghostwriters who do all the real writing, while another individual takes the credit. This can include works attributed to celebrities, deceased writers whose "lost manuscripts" keep turning up, and living authors who don’t want to be bothered doing the work anymore.