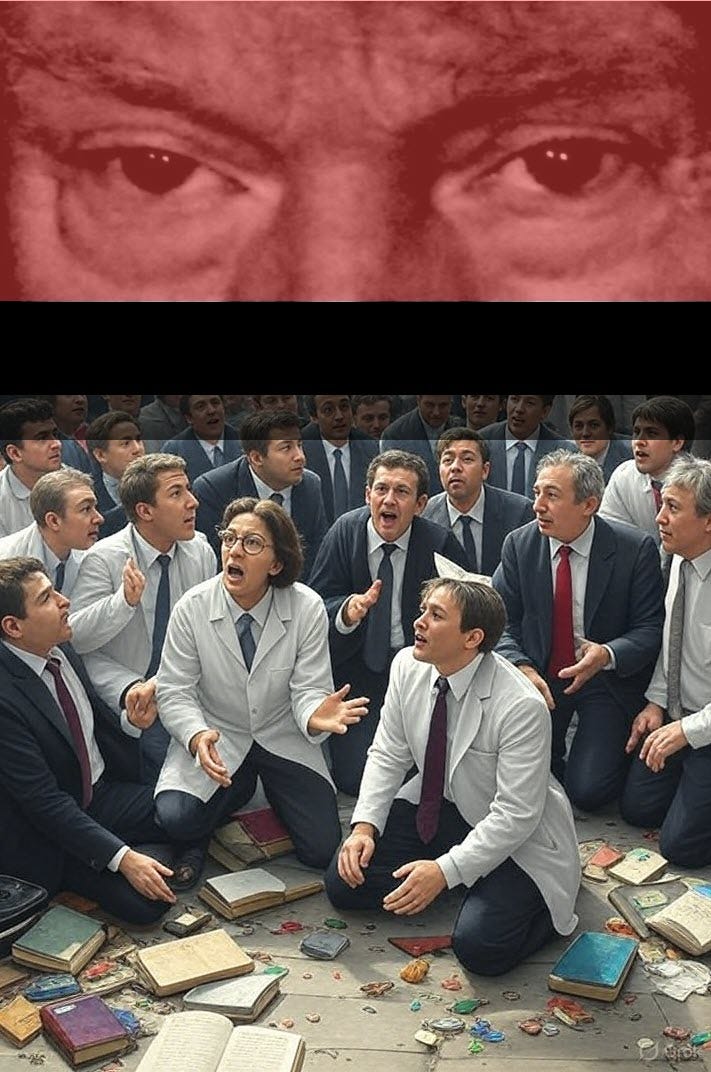

"Kill Everyone with Glasses"

Populist uprisings frequently share the same horiffic tendencies to destroy elites, intellectuals, and institutions

“In brief, the Maoist revolution and above all the ‘cultural revolution’, was the revenge of the ignorant over the educated, the triumph of obscurantism, the meritocracy of our own world turned on its head: the fewer degrees you had, the more power you attained.” — Henri Locard in Pol Pot’s Little Red Book

“They were killing anyone who wore glasses.” —On the Khmer Rouge1

The Trump administration’s know-nothing attacks on science and scientists are so irrational, so palpably self-destructive that it may feel historically unique—an unfortunate consequence of the President’s peculiar hatreds. In my previous post, I wrote about the administration’s shameful effort to deport Harvard scientist and anti-aging researcher, Kseniia Petrova, back to Russia. And today, Richard Hanania noted the administration has canceled various grants at Harvard, including a breast cancer study with 116,000 women dating back to 1989; a cancer study involving 52,000 men extending back to 1986; another 7-year project on the evolution of cancer, studies on reversing aging, ALS, etc. He concluded: “Conservatives are celebrating today—reaching levels of nihilism I didn’t think were possible.”

Still, as the quotes about the Khmer Rouge indicate, our situation is not unique. Pol Pot’s totalitarian regime led to the death of 1.5 to 3 million Cambodians out of a population of 7.7 million, whether through malnutrition, disease, or murder. But Pol Pot’s loyalists were especially savage with the intellectuals. Various reports suggested they managed to seek out and execute 90% of all doctors in the country and other classes of professionals and academics as well. According to Benedict Lin et al.:

The country’s physical and institutional structures were all but decimated … In this period, it has been estimated, that apart from professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and engineers, 90% of the nation’s schoolteachers were murdered, and that, out of 1000 university teachers, only 87 survived.2

Notoriously, Pol Pot’s militaristic enforcers believed only intellectuals wore glasses, hence they especially targeted the bespectacled.

Another notorious slaughter of the elites occurred during the French Reign of Terror (1789-99). After France’s “Comittee of Public Safety” brought the French nobleman and chemist, Antoine Lavoisier, to the guillotine, the mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange famously lamented: "Il ne leur a fallu qu'un moment pour faire tomber cette tête, et cent années peut-être ne suffiront pas pour en reproduire une semblable." ("It took them only an instant to cut off this head, and a hundred years might not suffice to reproduce its like.") Attacks on intellectuals were also the focus of the Stalinist Purges in Russia (1936-38) and Eastern Europe (1940s-50s), China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76); the purges in Iran (1979-present), etc.

Each cleansing of intellectuals discussed above had its own rationalization: The Reign of Terror focused on the overly-Christian and supposedly monarchist sympathizers; Pol Pot’s crew was trying to create an Agrarian paradise; the purges in Iran targeted the insufficiently Islamic. But the real reason that so many of the revolutionary-faithful were willing to engage in such brutalities on the educated is the same: we are savage, territorial primates who resent those higher up in the hierarchy. We also distrust the other too—which explains ethnic violence. Envy (i.e., hierarchy-based resentments) and xenophobia are among the main drivers of organized violence in chimpanzee tribes. And the same is true with human tribes.

As noted in the quote above by French Historian, Henri Locard, the Maoist revolutions of East Asia in the last half of the 20th-century represented “the revenge of the ignorant over the educated … the meritocracy of our own world turned on its head: the fewer degrees you had, the more power you attained.”

And speaking of kakistocracies, consider:

This is your Secretary of Defense right now:

This is your FBI Director:

This is your Deputy Director of the FBI:

This is who’s been placed on the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council:

This is your Education Secretary:

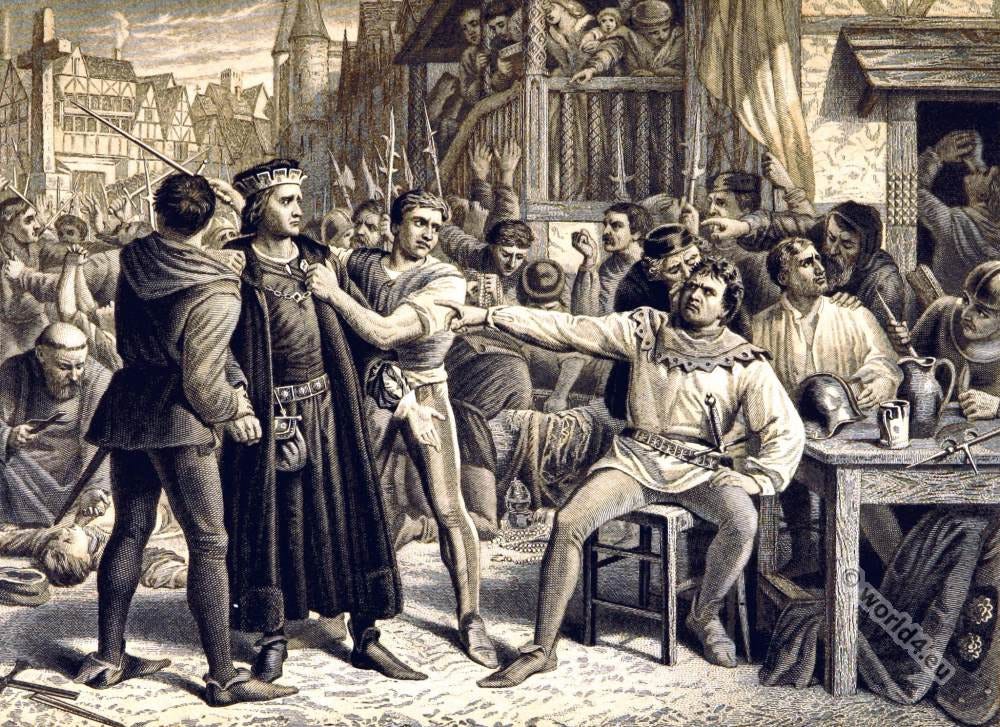

Shakespeare (North) and the Trump-Led Populist Take-Over (2016-2025)

[Adapted from earlier post:] In Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics, Stephen Greenblatt explores the uncanny resemblances between Shakespeare’s most ruthless demagogues and Donald Trump. The book is an analogical masterpiece, underscoring the far-sighted predictiveness of Shakespeare’s histories and demonstrating their continued relevance today. But perhaps Greenblatt’s most remarkable chapter is his exploration of the remarkable parallels between Jack Cade (the populist rabble-rouser of 2 Henry VI) and the most famous political figure in the world right now. Greenblatt also exposes the familiar hatreds of Cade’s followers that we have seen in other populist uprisings.

For example, as Greenblatt observes, Cade is a crude agitator, working the grievances of laborers and always appealing to their darkest impulses. The rebel leader intends to be carried to the throne on the shoulders of tradesmen by reminding them of England’s past glories, making impossible promises to relieve their poverty, and, most especially, denouncing elites and foreigners. Cade says he will drain the swamp, or at least promises to be the broom “that must sweep the court clean …” (2 Henry VI 4.7.29). He will rid the government of “scholars, lawyers, courtiers, gentlemen” and other such “false caterpillars” that his followers blame for the decay of their country (4.4.36-37).

Cade and his followers also set up sham trials for treason so they may execute the elites whom they despise. When the mob catches a clerk, they accuse him of being able to read and write. The clerk admits to literacy, and Cade agrees with the mob’s demand for swift justice: “Away with him, I say! Hang him with his pen and inkhorn about his neck” (4.2.105-6). Even worse, another of their unlucky prisoners, the elderly and palsied Lord Saye, has “traitorously corrupted the youth of the realm in erecting a grammar school” (4.7.30-32). He will be beheaded.

Dictators, wars, rebellions, coups, ideological crazes, reigns of terror—all the political incidents that continue to repeat throughout history—do so for the same reason: the unbreakable chains of human nature eternally anchor us to our ancestors, and so we are often doomed to replay their tragedies. What’s past is prologue.

Cade also excites his rebel supporters with impossible economic promises, swearing to uplift the laborers who surround him, making everyone equal and everything free: “I thank you, good people—there shall be no money. All shall eat and drink on my score; and I will apparel them all in one livery, that they may agree like brothers and worship me their lord” (4.2.70-73). Everyone will be equal—except, of course, for Cade, who will be “their lord.” Cade will also get rid of Parliament—the people’s representatives—for he will decide on all laws: “Away! Burn all the records of the realm. My mouth shall be the Parliament of England” (4.7.12-14). His followers continue to cheer.

Perhaps most relevantly, Jack Cade appeals to the crowd’s sense of nostalgia and their hazy memories of England’s greatness during their childhood. As Greenblatt writes:

Jack Cade longs for the time when, as he puts it, boys played games of toss “for French crowns,” a time before the country was “maimed and fain to go with a staff” (4.2.145-50). Until weaklings led it astray, he suggests, England compelled its enemies to tremble before its power, and that glorious swaggering must now be recovered. He promises to make England great again.3

Cade intertwines this with appeals to his followers’ nativism, denouncing England’s humiliating loss of Normandy to France and stoking their hatred of all things French. Before Saye’s trumped-up-trial for treason, Cade mentions another one of his supposed crimes: “Lord Saye hath gelded the commonwealth and made it an eunuch; and more than that, he can speak French, and therefore he is a traitor” (4.2.160-62).

The parallels to Trump and his followers are so obvious it would be condescending to state them plainly. But importantly, in earlier posts on Trump and the Adoration of the Cruel, I noted that the former President and his most radical followers conform to a malignant dominance hierarchy (also discussed here): where the cruelty of a leader actually excites—rather than abates—the loyalty of his followers, who then eagerly try to help him execute his plans (as with the Jan 6 rioters).

After the trial, Cade has his followers behead both Saye and his son-in-law, Sir James Comer, then has their heads placed on poles, and tells his followers “to make them kiss one another, for they loved well when they were alive. Now part them again, lest they consult about the giving up of some more towns in France.” The rebels enthusiastically follow his demands to have the heads carried through “the streets, and at every corner have them kiss.”

We not only see similar examples of malignant dominance hierarchies throughout history—but also in the intra-tribal maneuverings and violence in chimpanzee groups. The evolutionary forces behind these pecking orders are not hard to determine. In our tribal past, by siding with a vicious leader and helping him attack the outgroup, individuals ensure that they rise within his hierarchy, which in turn, helps foment their own prosperity and that of their descendants.

History as a Predictive Force (North and Shakespeare)

Dictators, wars, rebellions, coups, ideological crazes, reigns of terror—all the political incidents that continue to repeat throughout history—do so for the same reason: the unbreakable chains of human nature eternally anchor us to our ancestors, and so we are often doomed to replay their tragedies. What’s past is prologue.

Before Thomas North began work on translating Plutarch’s Lives, many Tudor historians focused on the role of fortune as the prime shaper of events—on the capriciousness and unpredictability of fate as it hoisted some and destroyed others. Not so with the biographies of North’s Plutarch, which preached that character is destiny. North included this idea in the plays that Shakespeare later adapted, placing this tenet in the mouth of Cassius: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, / But in ourselves” (Julius Caesar 1.2.140-41). Our failures are not, as the earlier chroniclers would have it, the result of some cosmic design but are due to our own defects. And these same defects in people continue to reappear, nation after nation, century after century. While this line appears in Julius Caesar, a play taken from the pages of North’s Plutarch’s Lives, it also explains the theme of the English histories and the tragedies. North also wrote a relevant comment on this subject to introduce his Plutarch’s Lives:

Whereas [hi]stories are fit for every place, reach to all persons, serve for all times, teach the living, revive the dead, so far excelling all other books as it is better to see learning in noble men’s lives than to read it in philosophers’ writings.

That is the secret: study the character of past princes—search for the “learning in noble men’s lives”—to understand worldly events and especially the downfall of civilizations. This is, in fact, the entire purpose of Shakespeare’s histories and tragedies—using historical examples to warn about the tragic flaws of the human race and against similar outcomes arising again. Indeed, the playwright even drew many parallels between the Wars of the Roses/the Jack Cade rebellion and the civil wars/Roman citizen rebellion that accompanied the death of Caesar. The past repeats itself.

In his introduction to Plutarch’s Lives, North wrote that understanding history and the patterns that occur in men’s lives enables you to predict the future::

History is the very treasury of man’s life … It is a certain rule and instruction, which by examples past teacheth us to judge of things present and to foresee things to come

North would also repeat this same idea in 2 Henry IV (later adapted by Shakespeare), even using very similar language:

There is a history in all men’s lives, / Figuring the nature of the times deceased, / The which observed, a man may prophesy, / With a near aim, of the main chance of things / As yet not come to life … (3.1.80-84)

The verbal echoes include history-men’s lives, times, things-come, but it is the identity of thought that elevates the correspondence. This is not just yet another recycling of any of the thousands of North’s quotes in the plays but an expression of the thematic purpose of Shakespeare’s histories and tragedies. It is also a flashing arrow pointing to their Northern origin.

North then sums it all up. Plutarch’s objective, he writes, was to “setteth before our eyes the things worthy of remembrance that have been done in old time by mighty Nations, Noble Kings and Princes, wise Governors, valiant Captains, and persons renowned for some notable qualities …” He wanted to highlight the benefits of virtue and the perils of vice in the lives of the world’s most compelling personages, exposing them “when they were come to the highest, or thrown down to the lowest degree of state.” North also follows this template with the plays. Like Plutarch’s magnum opus, the plays tell history not through incidents but through lives. They focus not on dates and battles but on character, teaching about vice, virtue, and the climactic events of history by exposing the strengths and failings of people. This is the credo as taught by North in both his translations and his plays—as each dramatically documents corresponding histories that, in the words of Cassius, continue to “be acted over / In states unborn and accents yet unknown!” (Julius Caesar 3.1.113-14).

History repeats itself, here and everywhere. And the reason for this is not hard to find: we remain, after all, the same passionate and needy species that North wrote about more than four centuries ago—and that Plutarch had chronicled long before him. And this is the cause of all our tragedies.

We are reminded once more about the current plight of Harvard scientist, Kseniia Petrova. It is moving to read her essay in The New York Times in which she tries to save herself from being sent back to Russia (and likely imprisonment there.) In her essay, she makes sure to include colorful new images of tissue samples produced by her Normalized Raman Imaging microscope—the only such microscope in the world (because it was invented in her lab). She spoke hopefully and enthusiastically about how these images could lead to a better understanding and potential cures for cancer, Alzheimer’s, even aging. She thought this might help her with the administration and Trump’s followers. She probably wouldn’t even be able to fathom that this effort may even diminish the sympathy of her tormentors.

To many of them, working with such microscopes is the modern-day equivalent of wearing glasses.

Congressman Stephen Solarz on the Khmer Rouge, as quoted by Brendan January, Genocide: Modern Crimes Against Humanity (Minneapolis: 21st Century Books, 2007), 66.

Benedict Lin et al., “English-Medium Instruction in Higher Education in Cambodia,” in Kingsley Bolton, Werner Botha, and Benedict Lin, eds., The Routledge Handbook of English-Medium Instruction in Higher Education (New York: Routledge, 2024), 429-449: 432.

Stephen Greenblatt, Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics (New York: W. W. Norton, 2018), 41.

Your Thomas North hypothesis is well thought out and your arguments are very convincing. However, I don't think your Trump Derangement Syndrome postings add to your credibility.

Shakespeare / North is offering lessons for our times. He’s perennial.