Picture-Proof of Thomas North's Authorship of a Shakespeare Play: A Response to David W Richardson

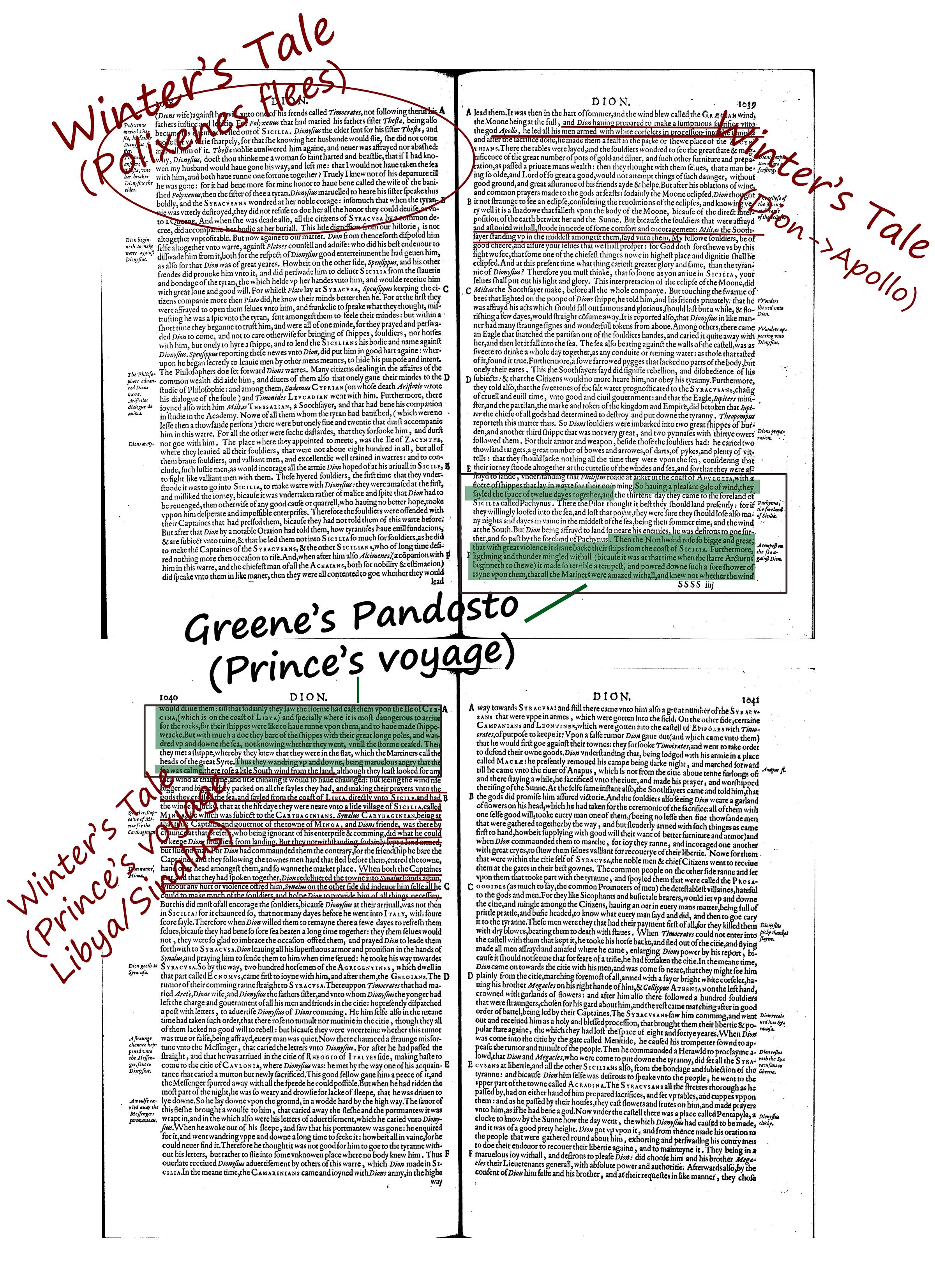

The augmented picture below of pages 1038-1041 of Thomas North’s Plutarch’s Lives is one of

’s favorite proofs of North’s original authorship of one of Shakespeare’s plays. It takes a few minutes to fully understand, but it proves beyond a reasonable doubt that Shakespeare could not, as is commonly supposed, have borrowed the story of The Winter’s Tale (1609) from Robert Greene’s romance, Pandosto (1585). Instead, the picture confirms that both Greene and Shakespeare had to be basing their tales on an earlier text—almost certainly a play by North. I will explain exactly what the picture means below.

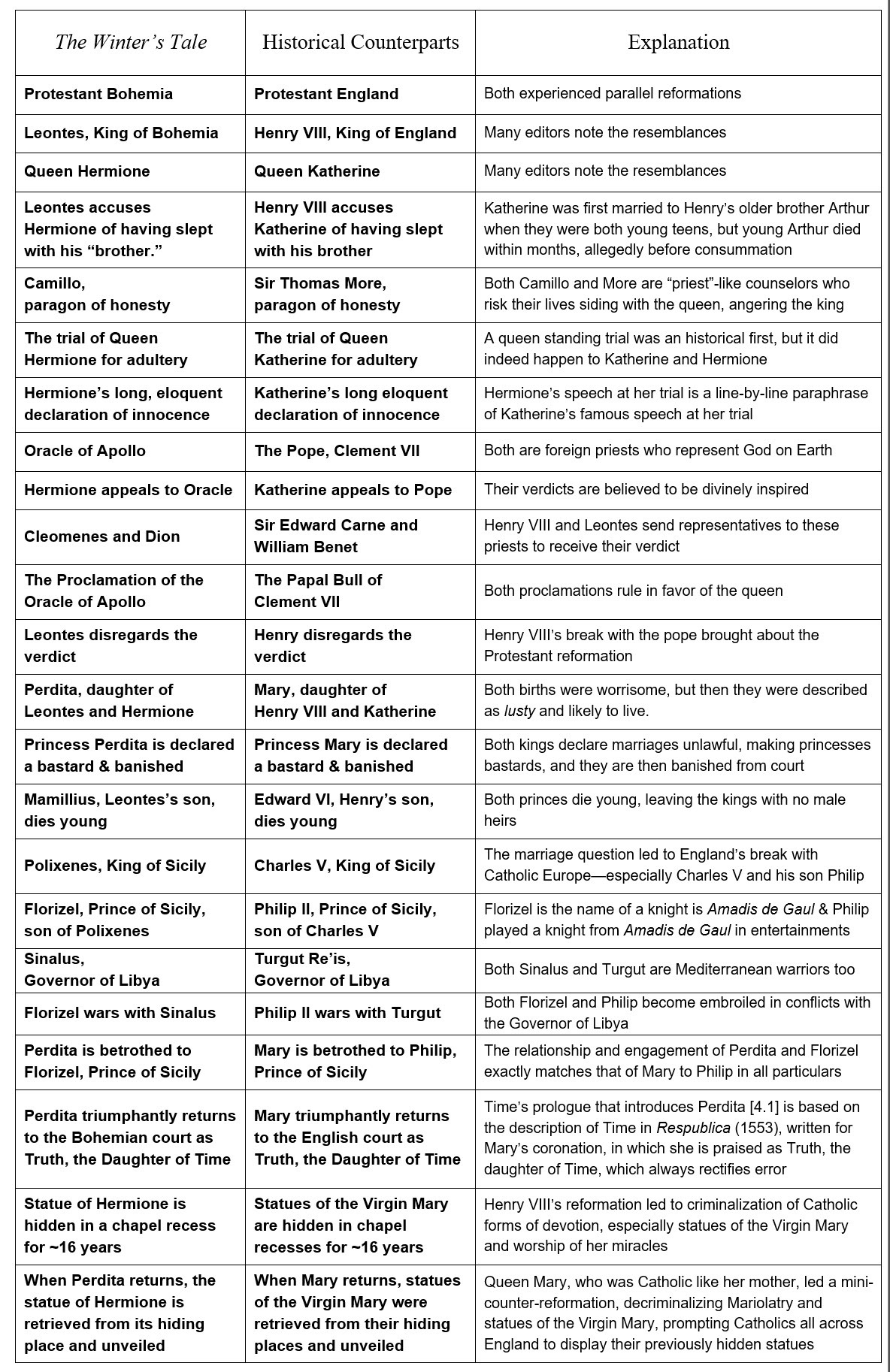

The picture above and the explanation that follows is in response to David W Richardson’s1 challenge to my recent post on Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, in which I show that the play is an allegory on the life of Queen Mary (Perdita in the play), beginning with the divorce of her mother Katherine (Hermione) by Henry VIII (Leontes). In fact, the nine major characters of the play correspond in a very conspicuous way to their nine historical counterparts involving Henry VIII’s marriage matter—and everything they do and every one of their peculiar characteristics help confirm their historical identity.

Richardson writes, “Presented in isolation, as McCarthy does, these parallels seem convincing; however his argument falls apart when the acknowledged sources of the play are considered.” Importantly, June Schlueter and I have written a peer-reviewed, academic book—“Thomas North’s 1555 Travel Journal: From Italy to Shakespeare”—focusing on the fact that Thomas North used the experiences documented in the journal to write early versions of Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale. And in that book, we do address Richardson’s point about the sources for The Winter’s Tale. In fact, as I will show here, a close examination of the sources also proves North’s authorship.

Again, Richardson writes that the parallels I listed linking The Winter’s Tale to the life of Queen Mary seem convincing when presented in isolation. But, of course, the following list of correspondences is either reasonably attributable to coincidence or it is not—and other facts of the play cannot change that fact. And as we shall see, those other facts also confirm North crafted the play as an allegory for the life of Queen Mary.

In the relevant post, I also put forth a table listing the correspondences between George Orwell’s Animal Farm and the Russian Revolution, followed by the table above. The comparison confirms that The Winter’s Tale allegory relies on far more peculiarizing details and is more conspicuously tethered to its historical model than Animal Farm. And no one denies the reality of the Animal Farm allegory.

Just consider the fact the divorce trial of Katherine was certainly the most famous divorce trial in English history, and the extensive legal maneuvers surrounding it, including Katherine’s famous appeal to the pope, ended up resulting in England’s break with Catholicism. All educated 16th-century citizens, whether they were Protestants or closet Catholics, were well aware of the trial and outcome. Moreover, Hermione’s speech at her divorce trial is a line-by-line paraphrase of Queen Katherine’s speech at her divorce trial—and scholars know this. In other words, they do not deny the connection between Hermione and Queen Katherine. As Schlueter and I write:

While few scholars have detected the full extent of the parallels between The Winter’s Tale and the life of Queen Mary, many have discussed the most blatant ones. Gordon McMullan, in the Arden edition of Henry VIII, compares the corresponding passages, noting that “Katherine’s defence of her marriage in the Blackfriars courtroom has strong resemblances to Hermione’s resistance to Leontes’ irrational jealousy.”2 Table 6.2 includes the parallels pointed out by McMullan and adds a few more.

Other scholars have also noted some of these resemblances. As Michael Dobson observes: “The difference between the two cases is that whereas Hermione is on trial for adultery, Katharine is accused of incest, but the way in which the latter trial seems deliberately to recall the former invites us to parallel or conflate them …”3 Dobson refers to Katherine’s crime as “incest” because of the accusation that she had sex with both Henry VIII and his brother. As we have shown, the situation with Hermione is actually not that different, as both Leontes and Polixenes repeatedly refer to each other as “brother.” More significantly, he is also correct that the playwright has deliberately modeled the speeches of the one on the other. But as North had written Henry VIII prior to The Winter’s Tale, it is Hermione’s that is following Katherine’s. And we know this had to be the case anyway as Katherine’s trial is factual and the playwright borrowed the trial scene of Henry VIII, including Katherine’s speeches, nearly verbatim, from Cavendish. This includes taking those elements (e.g., being a true and humble wife who has given him children, loving the king’s friends for his sake, being the daughter of a king) that also appear in Hermione’s speeches in The Winter’s Tale (see Table 6.3).

McMullan makes the same point in his gloss of Katherine’s speech in Henry VIII (2.4.11-55), noting that the queen seems to be following two different sources. Katherine’s speech, he states, “is effectively versified Holinshed” (i.e., Holinshed’s quoting Cavendish), adding that “Katherine’s speech here (and her situation in general) bears close comparison with that of Hermione at WT 3.2, especially 21-53 …”4 Yet how could Shakespeare, when writing The Winter’s Tale in c. 1610, invent out of whole cloth a speech for Hermione that miraculously anticipates Katherine’s verbatim reproduction of an historical speech in Henry VIII (1613)? Certainly, there is no doubt that the one scene seems “deliberately to recall” the other—but it is Hermione’s trial and speech that recall the actual trial and speech of Katherine. Cavendish’s quotations of Katherine obviously have precedence. And the playwright of The Winter’s Tale had to have studied these quotations of the historical Katherine prior to the crafting of the speeches of Hermione in the trial scene and then deliberately borrowed from them. The only reason the playwright would do this is if Hermione were meant to represent Katherine. The late date of Shakespeare’s adaptation of Henry VIII has obscured this obvious point.

Moreover, at times Hermione more closely follows the historical quotations of the real-life Katherine than does her counterpart in the history play …

The table below shows a few of the more conspicuous parallels between the queens’ declarations of innocence at their respective trials. The quotes of Katherine in Henry VIII (in left column below), closely follow the quotes of the historical Katherine.5

As no one denies, Queen Hermione and Queen Katherine share obvious similarities, and the trial of the former is undoubtedly based on the historical trial of the latter (a trial that is also recreated in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII.) On top of this, the pointed parallels continue:

Each queen appeals to a foreign priest for her judge (Katherine appeals to the pope; Hermione appeals to the Oracle of Apollo). In each case, this priest represents God on Earth, and his verdicts are believed to be divinely inspired.

Messengers are sent to this foreign priest (as Carne and Benet journey to the pope, Cleomenes and Dion travel to the Oracle of Apollo).

The foreign priest sides with the queen.

The king disregards the verdict of the foreign priest, breaks with him, and declares her guilty anyway.

As a result of the outcome of the queen’s trial, the daughter’s title of princess is rescinded. She is declared a bastard and banished from the court.

The queen prays for blessings to be poured from the heavens upon her daughter’s head (Henry VIII 4.2.132-33, Winter’s Tale 5.3.122-24).

There is a pastoral feast with beautiful women and royalty disguised as shepherds (Henry VIII 1.4, Winter’s Tale 4.4).

The queen dies soon after being deposed, appearing in a ghostly vision in white robes; the vision then vanishes into the air (Henry VIII 4.2.82.s.d., Winter’s Tale 3.3.16-36).

Surprisingly, the king’s young prince dies (the young Edward VI in 1553, Mamillius in Winter’s Tale), leaving the king with no remaining legal heirs, a fate thought by some to be divine punishment for his false accusation and abandonment of his queen.

The banished daughter, who has now grown up, regains her royal status and is betrothed to the Prince of Sicily (Perdita marries Florizel, Queen Mary marries Philip II).

This Prince of Sicily is a Mediterranean warrior involved in a conflict with the Governor of Libya (Sinalus, Turgut Re’is [a/k/a Dragut Rais]).

The Prince of Sicily emulates the heroic knights of the Spanish romance Amadis of Gaul (i.e., Florizel is a knight from Amadis de Gaul, and Philip II would appear as an Amadis de Gaul knight in entertainments).

During the heralding of the daughter’s triumphant return, the princess is described as Truth, the daughter of Time, which always rectifies error. (Time’s Prologue that introduces Perdita [4.1] is based on the description of Time in Respublica (1553), written for Mary’s coronation.)

The repeated celebration of Catholicism throughout The Winter’s Tale—including Catholic festivals, Mariolatry, supplication to a statue of a woman in a recess in a chapel, and a miraculous resurrection—speaks to Mary’s decriminalization of idolatry, festivals, and miracle stories in England.

Certainly, it is irrelevant what the other sources of The Winter’s Tale are, the play is indisputably an allegory of the life of Queen Mary (Perdita), starting with the divorce trial of her mother Katherine (Hermione). And the few alleged inconsistencies that Richardson believes challenge this interpretation are the result of his own errors—none more flagrant than the following:

“Most of the parallels between Katherine and Hermione which McCarthy cites as proof positive that the story must be a thinly veiled roman-a-clef of Henry’s first marriage and divorce are also present in Chaucer’s tale of the patient Griselda, including the husband obtaining a Papal annulment.”

While Richardson’s other points are understandable and fair, this one is not. This is not within a galaxy of being true. Yes, Chaucer’s Griselda is likely another source for The Winter’s Tale (most plays have at least half a dozen sources). Yes, both Griselda and Hermione are tortured symbols of wifely patience. But essentially nothing from Griselda’s brief story can explain any of the parallels between Hermione and Queen Katherine (let alone Leontes and Henry VIII; Perdita and Queen Mary; Florizel and Philip; Mamillius and Edward VI; the Oracle of Apollo and the Pope; Carne and Benet and Cleomenes and Dion; Camillo and Thomas More; Turgut Re’is and Sinalus, etc.) The only true plot similarity is that servants come to take Griselda’s children away from her, and they are reunited more than a decade later. Richardson also mentions “the husband obtaining a Papal annulment”—evidently forgetting that there is no pope in The Winter’s Tale. Schlueter and I introduced the fact that the Oracle of Apollo represents the pope in our book on North’s journal, and, accepting that, again identifies Hermione as Katherine and establishes the pro-Catholic slant of the play. What’s more, in The Winter’s Tale, the pope-like figure does not side with the husband and grant the annulment—but sides with the queen and rejects the grounds for divorce (just as the pope did with Katherine.)

Finally, in a more recent note, Richardson writes, “I would point out that an equally detailed argument was made for Anne Boleyn as Hermione in Ives 1986.” Again, of course, the argument for Anne Boleyn is not as “equally detailed” as the one Schlueter and I have put forth for Katherine. Richardson’s statement is not a serious comment. In fact, essentially all the similarities shared by Hermione and Anne Boleyn derive from the important fact that, as scholars have recognized, correctly: 1) the play is an historical allegory; 2) Leontes is Henry VIII; 3) Hermione is one of his rejected wives, and 4) Perdita is the daughter who returns to become Queen. Scholars are 100% right about all that. But as is unsurprising, scholars accepting Shakespeare’s origination of the play assume that daughter would have to be Elizabeth—and so Hermione must be Anne Boleyn. But as shown above, the fact that Katherine is that queen (and Mary is that daughter) is really not disputable. Again, consider all the pointed correspondences connecting Hermione’s and Katherine’s trial—and the fact that Mary really did marry the Prince of Sicily, who really was at war with the Governor of Libya, and who really did play knights in Amadis de Gaul, etc. In contrast, Elizabeth never married, Anne Boleyn never appealed to the pope, etc.

Importantly and again, the fact that some conventional scholars have indeed recognized that The Winter’s Tale is an historical allegory and that Leontes is Henry VIII—far from militating against my view—is actually a giant and welcome step toward the correct interpretation of the play.

Was Shakespeare Working from Greene’s Pandosto or from North’s Winter’s Tale?

Richardson is on firmer ground when he writes that, in the conventional view, “the story for the play is taken from and closely follows a prose romance by Robert Greene, Pandosto, published in 1588” (yes, and Greene had likely written it by 1585). Richardson continues:

If in fact the play is substantially as North wrote it more than 50 years earlier, we would have to credit him with anticipating and inspiring the work of Greene and Sidney as well as the (debated) author of Musidorus

Great point. And in Thomas North’s 1555 Travel Journal: From Italy to Shakespeare, Schlueter and I provide evidence confirming behind a reasonable doubt that this was indeed the case. Shakespeare could not have been following Greene—rather Greene and Shakespeare were both following North. As we write:

We know from his writings that North was an inveterate reviser. … [examples deleted] Revisions were not unusual for the time. Ben Jonson is known to have revised his work repeatedly. For the only collection of his works (1616), he changed the names of the major characters in Every Man In His Humor (1598). Shakespeare also revised, not always with great care. One of his more famous revisions was the change of Sir John Oldcastle’s name to Sir John Falstaff. In the late 1570s or early 1580s, North likewise reworked his Winter’s Tale, changing the original names of several characters. We are not sure why he returned to this decades-old play at that particular time, but it is possible that the original names were random, with no suggestive meaning—or perhaps he had originally adopted the early Tudor practice of using allegorical names like Jealousy, Truth, Patience, etc., which would have become old-fashioned by the 1570s. Whatever his reason, he replaced the names of six of the characters with an historically suitable set of names that he found in his most recent translation: Plutarch’s Lives (1579/80). Specifically, he took Polixenes, Dion, and Sinalus from the chapter on “The Life of Dion”—all from pages 1038-40—and borrowed Leonidas (Leontes), Archidamus, and Cleomenes from “The Life of Agis and Cleomenes,” especially focusing on page 857.

Leonidas, “Son of the Lion,” offered an appropriate name for Leontes, King of Bohemia, whose symbol was the lion. In Plutarch’s Lives, King Leonidas had married a foreigner and ordered the murder of a rival king and that king’s brother, Archidamus. The latter discovered the plot and managed to flee to Sicily. Similarly, in The Winter’s Tale, King Leontes had married a foreigner and ordered the murder of King Polixenes and presumably his lord, Archidamus. The plot is discovered, and they manage to escape back to Sicily. In Plutarch’s Lives, Cleomenes is the son of Leonidas, and his name appears in the title of the chapter. He is also discussed in the relevant passage on Leonides and Archidamus. In The Winter’s Tale, Cleomenes is the name for Leontes’ trusted messenger.

The name of the other messenger, Dion, also derives from the title character of a later chapter. According to North’s “Life of Dion,” before the Greek king traveled across the Mediterranean to liberate Syracuse in Sicily, Dion took advice from the Soothsayer Miltas and made a sacrifice in the Temple of Apollo (1038-39). Thus, in The Winter’s Tale, Dion becomes the name of the Mediterranean messenger who, along with Cleomenes, visits the Oracle at the Temple of Apollo in Greece.

In the same Plutarchan chapter—indeed, on the very same pages—North also recounts a story of the Sicilian prince Polyxenus, the son of Dionysius, who had married his father’s sister, infuriating the king and causing Polyxenus to flee in secret. This story would have reminded North of his own Sicilian (not Bohemian) monarch in The Winter’s Tale, who also fled in secret in order to escape a king whom he had enraged for an alleged, quasi-incestuous dalliance. Thus, in Plutarch’s Lives, both Polyxenus and Archidamus are connected to Sicily, and both must flee for their lives after angering a king—like their namesakes in the play.

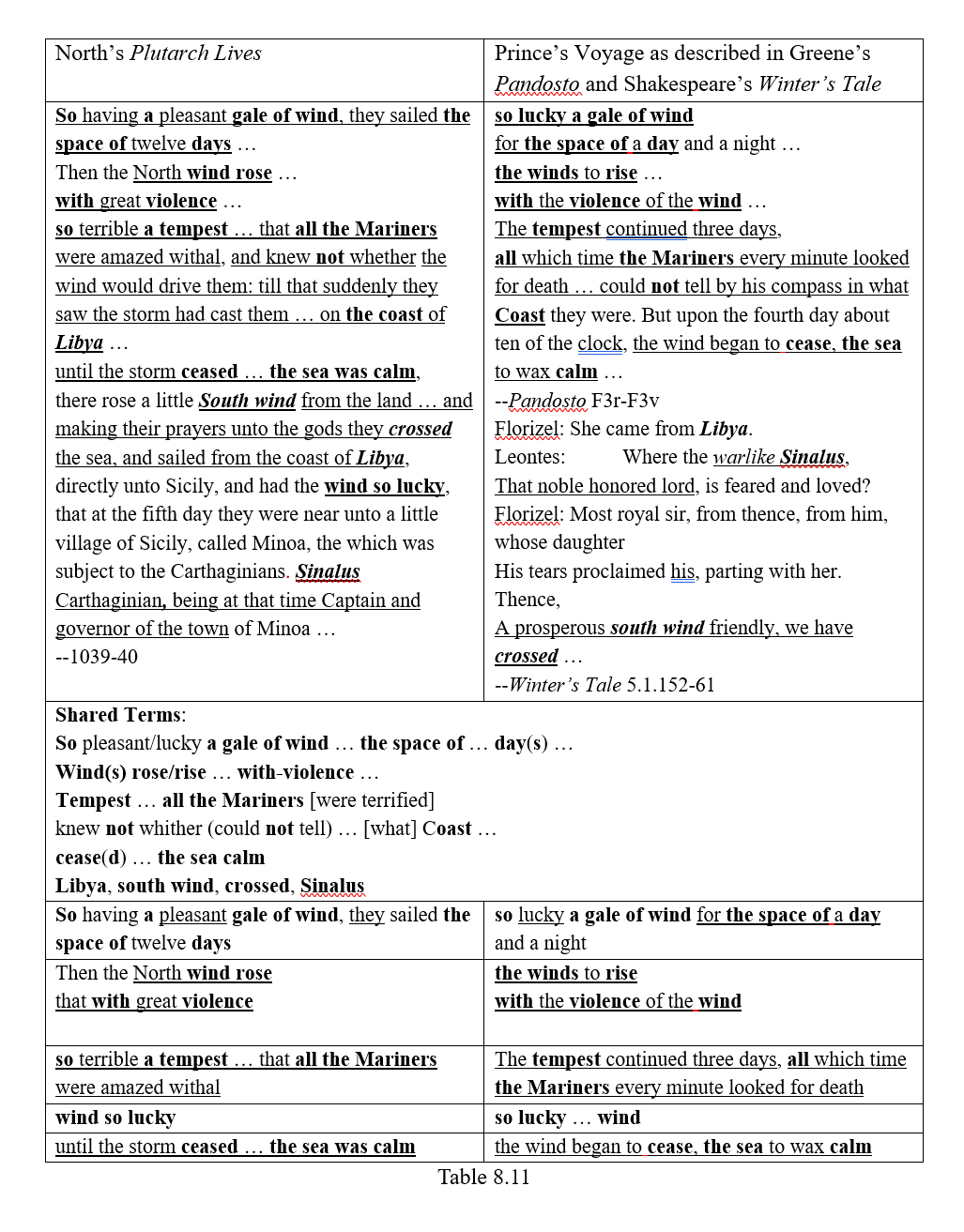

We also find that during this revision of The Winter’s Tale, North adds a brief story about Florizel (or perhaps augments an earlier one) that further connects the play to this particular section of the chapter. Specifically, on these same pages—1039-40—North describes how a storm blew Dion’s ships across the Mediterranean to Libya, then “there rose a little South wind” and “making their prayers unto the gods they crossed the sea, and sailed from the coast of Libya” (1040) to Minoa, a Sicilian port-city then controlled by a noble North African captain and governor, Sinalus Carthaginian. Fortunately for the Greek Dion, Sinalus was an old friend.

Here we find the origin of the name of the North African warrior-lord from Libya in The Winter’s Tale. Desiring to give Perdita nobility, Florizel falsely claims to Leontes that she is the daughter of Sinalus, ruler of Libya, where, for some unknown reason, Florizel had stopped before he traveled to the kingdom of Leontes. As noted, the fact that Florizel is in conflict with a Governor of Libya reflects the historical circumstances of his counterpart, Philip II, prince (then king) of Sicily, who in the 1550s was at war with the Governor of Libya, Turgut Re’is. As with Sinalus, Turgut had indeed taken over and controlled parts of Sicily—and, as mentioned, North had recorded the 1555 attack of Turgut on Calabria in his journal (while discussing Ferdinand, King of Bohemia) (3 July).

The false identity that Florizel gives Perdita, making her the daughter of an enemy, also corresponds to their current situation. And Florizel’s alleged reconciliation of Sicily and Libya through engagement to the Libyan princess foreshadows the ending of the tragicomedy in which marriage to the Bohemian princess would signal the reconciliation of Bohemia and Sicily (and England’s uniting with Sicily and Catholic Europe).

Florizel seems to bring up Perdita’s invented background apropos of nothing, responding specifically to Leontes’ concern about the dangers of the sea:

Leontes: … And hath he too

Exposed this paragon to th’ fearful usage—

At least ungentle—of the dreadful Neptune,

To greet a man not worth her pains, much less

Th’adventure of her person?

Florizel: Good my lord,

She came from Libya.

Leontes: Where the warlike Sinalus,

That noble honored lord, is feared and loved?

Florizel: Most royal sir, from thence, from him, whose daughter

His tears proclaimed his, parting with her. Thence,

A prosperous south wind friendly, we have crossed (5.1.152-61)

An EEBO search for south wind NEAR.100 Libya NEAR.100 cross yields only The Winter’s Tale and the relevant passage in North’s chapter on Dion—and both passages are referring to the feared North African ruler, Sinalus. This borrowing is well known, and the conventional claim that this page in North’s Plutarch’s Lives was the source for this description is indisputable.

But why does Florizel’s story include no explanation for why he was in Libya? Because Shakespeare took it out. Notice that Leontes’ expression of concern for the perils of sea voyage—with the threat “of the dreadful Neptune”—would seem to set up Florizel to relate a harrowing tale of a sea storm. Yet Florizel does not mention one even though at this precise moment in the supposed source tale, Pandosto, Greene does describe in detail a sea storm experienced by Florizel’s counterpart, Dorastus. And, remarkably, Greene’s description also derives from Plutarch’s Lives. In fact, it derives from the beginning of this very same passage on pages 1039-40.

As shown in Table 8.11, Dorastus’s storm in Greene’s Pandosto is based on the description of the very same tempest that blew Dion from Sicily to the coast of Libya just before he encountered Sinalus.

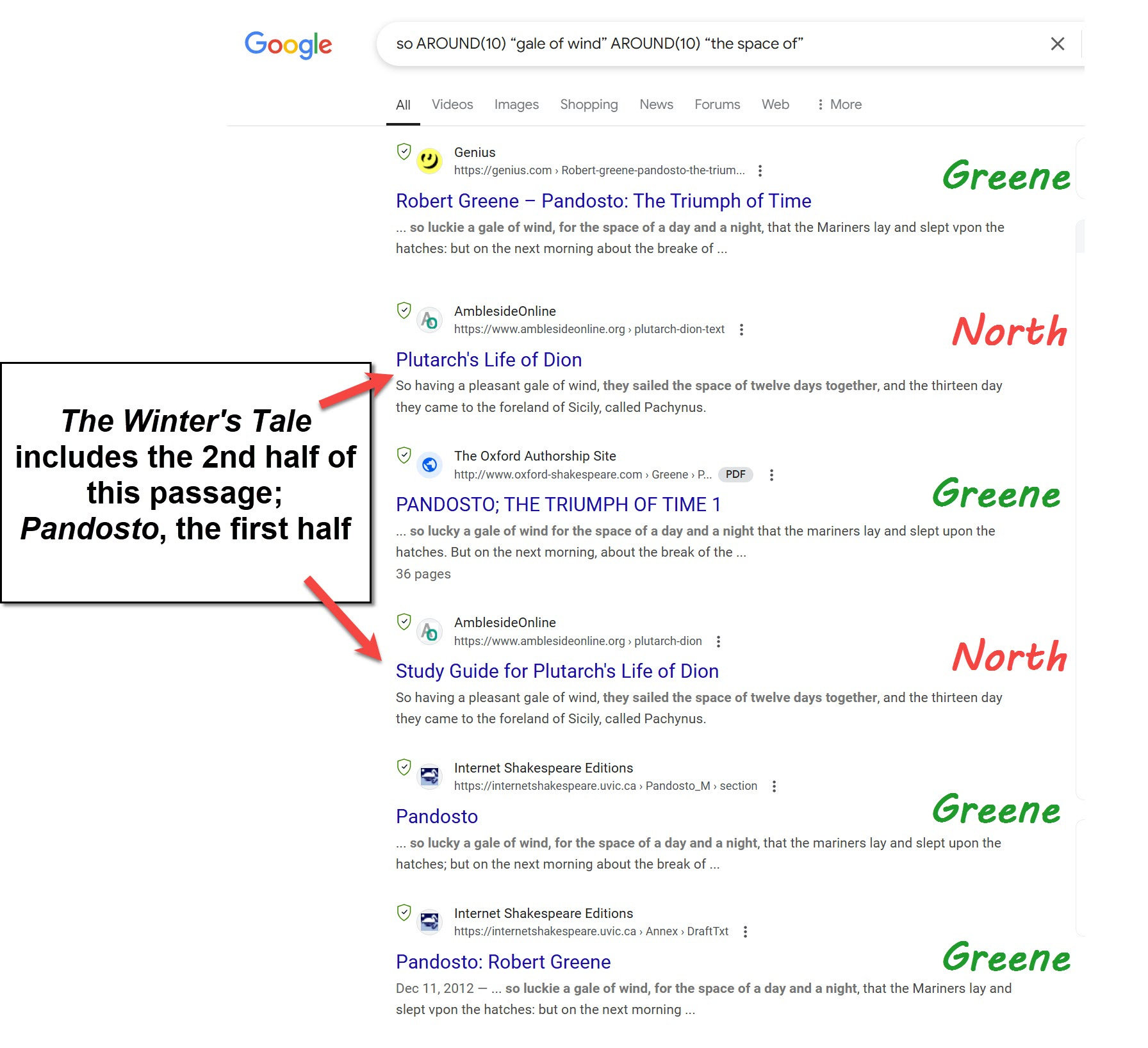

This connection is secure. Many of the lines that Greene borrowed from North are unique, and the descriptions even follow the same order. First, both ships start out with fortunate weather, that is, with so pleasant (lucky) a gale of wind for the space of a day (or days). We need go no further. An EEBO search for just the first correspondence—so FBY gale of wind FBY the space of—yields only this exact storm pushing Dion’s ship from Sicily to Libya in North’s Plutarch’s Lives and Dorastus’s storm in Greene’s Pandosto. Again, a search of both Google and Google Books for so AROUND(10) “gale of wind” AROUND(10) “the space of” yields only these same two passages of North and Greene (see image below).

This unique connection is then followed in both works by a series of peculiar events, all of them similarly worded 1) wind-rose/rise … with-violence, 2) tempest … all … the Mariners (astonished), 3) the Mariners knew not whither (could not tell) what coast they were blown to, 4) the storm then cease(d)—the sea, calm. In Plutarch’s Lives, this is then followed by the Libya, Sinalus, south wind, crossed passage, which is indisputably the source of the corresponding passage in The Winter’s Tale.

Importantly, Greene’s Pandosto has none of the other Plutarchan names and no other Plutarchan elements. As Greene apparently takes nothing else from the tome, there is no reason for him to decide to flip through the pages of Plutarch’s Lives to find a description of a sea storm. And even if he had, the text refers to dozens of other squalls—and includes the term storm or tempest 89 times. So why would he turn to this particular passage, running from the bottom of 1039 and extending to 1040, to borrow the wording of a description of a storm that he could have easily written himself? And even if we choose to believe that Greene did act in such a manner and did randomly choose that page, how would it have been possible that, 25 years later, when Shakespeare adapted Greene’s Pandosto, he would at the very start of the play, again like Greene, turn to these same pages of Plutarch’s Lives, 1038-40, and start assigning characters’ names from these pages—Polixenes, Dion, and Sinalus? Then, at the point in the story where Greene borrows the description of a storm, Shakespeare has Florizel start talking about a voyage from Libya that begins on page 1040 right where Greene’s source passage ends. And why is there no explanation for how Florizel was blown from Sicily to Libya? This is all the more inexplicable given that this Plutarchan passage describes a storm that blows ships from Sicily to Libya!

None of this could have occurred by chance. No, Greene and Shakespeare did not—at precisely the same moment in their shared storyline—borrow different halves of the same long passage in Plutarch’s Lives. Rather, both Greene and Shakespeare were following the same source play, and it is this work that had all the Plutarchan elements and Northern language from these pages, some of which ended up in Greene’s tale, some in Shakespeare’s play. Thus, this earlier Northern version included this same storm from Plutarch’s Lives that blew ships from the coast of Sicily to Sinalus’s Libya. In other words, in North’s version, when Leontes asks about the dangers of sea travel and “the dreadful Neptune,” Florizel does not just oddly change the subject with “She came from Libya.” He first describes the storm that carried him from Sicily to Libya, then he discusses his interaction with Sinalus and the meeting of Perdita, his “daughter.” Then North’s Florizel—as with Shakespeare’s Florizel—discusses the “prosperous south wind friendly” with which they crossed the sea. Shakespeare cut out the first half of this description, perhaps because there was another description of a sea storm earlier in the play (3.3), but Greene kept the storm. The result is the ostensibly fantastic circumstance of two authors, writing 25 years apart and both working independently on the same storyline, both seemingly opening up a third text and borrowing two different parts of the same passage when relating the same event.

All this evidence supplied by Greene’s Pandosto is probative. Though writing at least 25 years apart, Greene and Shakespeare both appear to have borrowed independently from 1) Herberay’s Amadis de Grecia, 2) North’s Dial, and 3) North’s Plutarch’s Lives. North’s Dial is the origin of the Isle of Delphos error in both Green’s prose work and Shakespeare’s play, and each work includes different elements and language from North’s Oracle-related stories. From North’s Plutarch’s Lives, both works incorporate different halves of the same passage to describe the same voyage. Again and again, we find facts that admit only one explanation: North, shortly after his trip to Rome, wrote two plays on Henry VIII’s divorce of Katherine—one a straightforward history, the other an allegory based on his continental journey. Half a century later, Shakespeare reworked these plays as Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale.

Finally, Richardson notes that the style of the play is consistent with Shakespeare’s late plays: “the tangled speech, the packed sentences, speeches which begin and end in the middle of a line, and the high percentage of light and weak endings are all marks of Shakespeare's writing at the end of his career.” Yes, there is no doubt Shakespeare adapted the play in 1609, and most of these stylistic quirks are the result of Shakespeare’s modifications. His hand is much heavier in the late plays—Pericles, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, Henry VIII, The Tempest—leading to an increase in “light and weak endings,” etc.

Summary: The Winter’s Tale, Henry VIII, and North’s Life (From Thomas North’s 1555 Travel Journal: From Italy to Shakespeare)

The original purpose of both Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale has now taken form: as an ambitious young writer, Thomas North would naturally feel drawn to celebrating the wondrous history of his new queen, who was the dedicatee of his Dial and had just sent him on his life-changing mission to Rome. His study of George Cavendish’s unpublished manuscript and Edward Hall’s history of the life of Henry VIII—both of which he had consulted for his journal—encouraged him to write a history play on the dequeening of Mary’s mother, and then an allegory on the same subject.

While this tragic story of Katherine provides the basic plot outline for both plays, North’s visits to Mantua and Rome explain many of the plays’ striking images and exotica. In The Winter’s Tale, this includes North’s eye-opening experiences with the lavish palaces in the realms of Ferdinand and Charles V (i.e., the Kings of Bohemia and Sicily); the lifelike painted statues in a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary and decorated by Giulio Romano; striking scenes of faith in miracles, especially a poignant prayer for a resurrection in the blizzards of a barren mountain; con artists displaying fake popish relics, including a horn-ring in lawn; his interaction with a very honest Camillo at a wedding celebration; a banquet at the Sala di Psyche at Palazzo Te in Mantua, with Giulio Romano’s frescoes of a pastoral feast of the petty gods, with Flora, dressed as spring, distributing flowers, fire-robed Apollo dressed as a humble swain, porters carrying sacks of goods from the spice trade, multiple satyrs, Jupiter changing into a beast to seduce a mortal woman, Proserpine and Dis, Juno, and Cythera. All of these seemingly impossible and fantastic elements—all of the striking visions that make The Winter’s Tale seem so otherworldly—all this we find in North’s trip to Rome.

And these are not commonplace experiences. For many years, various scholars have assumed Shakespeare got his information about Giulio Romano from some traveler to Mantua. But though many have searched, no one has been able to place a Shakespeare-era Englishman in Santa Maria delle Grazie—let alone one expressing astonishment at its lifelike wax figures. According to Rita Severi and our own research, North is the only known traveler prior to 1610 to provide a description of the chapel’s interior. He then follows this with a visit to Giulio’s most extraordinary achievement: the Palazzo Te. Similarly, some scholars find the notion of the realization of a resurrection in a chapel so outlandish that they contend Hermione never died. Yet North witnessed just such a prayer for a miraculous resurrection of a dead body—and did so among the perpetual storms of barren mountains, just as described by Paulina. After visiting Mantua, North enjoyed the grand international banquets of the Duchess of Pesaro followed by a stay in Rome, where he describes a fabulous procession of cardinals and the pope sitting in his consistory. These served as the basis for similar scenes in Henry VIII.

To those familiar with both Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale, the relevance of various descriptions in North’s journal is quite conspicuous. Still, we have also enlisted the aid of forensic linguistics and its associated research tools to unearth additional evidence that Thomas North originally wrote these plays that, decades later, Shakespeare adapted. Through the use of digital search engines and plagiarism software, we have uncovered the ways in which texts by William Thomas, George Cavendish, and Edward Hall served as sources for North’s journal. And many of these same source passages that North used for his journal, he then used in Henry VIII, even connecting the same widely separated source passages that North had juxtaposed in his journal. At the same time, the playwright frequently veered from the historical source text to incorporate North’s language and experiences—including the conflation of the descriptions of the consistory and cardinal parade and adding the costumed women of carnival to Anne’s procession. Finally, we have shown that North’s Dial of Princes, also written between 1555 and 1557, was the origin of many elements and passages in both Winter’s Tale and Henry VIII.

Though this is not germane to the veracity of his arguments, it is still apposite to note that David W Richardson is not a disinterested observer but an anti-Stratfordian who contends Mary Sidney was William Shakespeare. In other words, if I am correct about The Winter’s Tale, Richardson would have to shelve his own view on the creation of the play. Also, I am unclear about his view of Shakespeare, but anti-Stratfordians typically believe that Shakespeare was just an illiterate stooge—a front-man for the real author of the canon who wanted to hide their identity for some reason. I am not an anti-Stratfordian, but do appreciate many of their arguments about the disconnect between Shakespeare and the plays. For example, the plays contain a considerable amount of inside information about Italy—even though there is no evidence that Shakespeare ever left England. Still, I agree with conventional scholars and all the documented evidence confirms Shakespeare’s existence and his work as a playwright. I just accept, like all scholars accept, that Shakespeare frequently adapted old plays. I am just showing that it was the well-travelled, hyperpolyglot Thomas North who wrote those old plays—and it is his readings and life experiences that shaped the canon.

Gordon McMullan, Introduction to King Henry VIII (All Is True), ed. Gordon McMullan (London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2000), 125.

Michael Dobson, as quoted in Gordon McMullan, Introduction to King Henry VIII (All Is True), 129. See Michael Dobson and Nicola J. Watson, England’s Elizabeth: An Afterlife in Fame and Fantasy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Gordon McMullan, ed., King Henry VIII (All Is True), 301.

Stunningly, the quotes of Katherine at her trial come from George Cavendish’s Life of Wolsey (~1554), a text North was reading and sometimes quoting when crafting his journal about his 1555 embassy to Rome. So, to be clear, not only is North’s journal an important source for Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale, so too is the text that North was studying when writing the journal.

Dennis, you wrote:

"I am not an anti-Stratfordian, but do appreciate many of their arguments about the disconnect between Shakespeare and the plays. For example, the plays contain a considerable amount of inside information about Italy—even though there is no evidence that Shakespeare ever left England. Still, I agree with conventional scholars and all the documented evidence confirms Shakespeare’s existence and his work as a playwright."

For over a decade now, I've been using the term "post-Stratfordian" (a friend coined it, and I embraced it two nanoseconds later) to describe my own particular POV on the role of Shakespeare of Stratford. By using this term, I'm trying to communicate my desire to peer BEYOND the standard mythmaking and the "miracle of genius" storylines woven around Shakespeare of Stratford by the last few generations of academics and pop biographers, alike.

To my mind, Shakespeare of Stratford, the fellow of Burbage, et al, is OF COURSE the man who was publicly being credited in 1590s and 1600s London, with creating a host of plays performed by the LC's & King's Men...and eventually printed and sold during his lifetime. He was just as surely considered as a playwright by various theater contemporaries, and, as a sharer in the company, intimately concerned with getting all LC's Men / King's Men productions from "page to stage". Period evidence makes this role plain to the vast majority of rational people, IMO.

The central question for a post-Stratfordian is this: "In light of the towering content found in the plays attributed to him, and considering what we know about Shakespeare's socio-economic background, his education and his travels & life journey, exactly HOW did he manage to do it?".

Any anti-Stratfordian theorist who suggests that Shakespeare of Stratford was just a barely literate, bumbling yokel acting as a front man, or worse yet, that he never really existed at all...and that the name "Shakespeare" was just an empty nom de plume or placeholder, must immediately resort to logical contortions worthy of a circus performer.

The real tragedy is that, in doing so, such vehemently anti-Stratfordian theorists not only destroy their own credibility with the average Shakespeare fan, but also the credibility of anyone else daring to ask logical and reasonable questions, including those regarding Shakespeare's typical working methods, his access to source materials and background knowledge, his possible writing associates/collaborators, and many other "how did he do it" type inquiries. That 'loss of credibility by association' is a major problem...

The other major problem with being a post-Stratfordian, is that it can be a fairly lonely road. One winds up being hated by both sides of the debate. Bullying, orthodox, brown-shirts protest your daring to ask 'uncomfortable questions' as they denounce the sin of "focusing too much on gossipy details rather than the works themselves" while hardcore anti-Stratfordians eye you with wariness (at best) or deep suspicion (at worst) for your refusal to denounce Shakespeare as the completely illiterate country bumpkin, which they hold him to be. It's not an easy path to walk.

Luckily, there is a long line of independent-minded scholarly research and writing, dating back to at least the 1800s, which supports the notion that Shakespeare's playwrighting efforts were centered as much around adaption, as they were with creation from a blank-page.

It seems to me, Dennis, that (when it comes to the role of Shakespeare of Stratford) you, and your prime collaborator June, are not only the latest in a very distinguished line of independent-minded scholars, but are likely in the process of going well beyond all of their discoveries combined.

Add this to your own remarkable discoveries involving North's central importance to the entire canon...with regards to vocabulary, storyline details, intellectual content, etc. ("the whole shebang", as the saying goes)...and you can see why I believe that you are literally changing the world of Shakespeare scholarship, as we know it.

-JDL

P.S. I suspect that its going to be a very bumpy ride for you on a personal level (think of Wegener and Semmelweis) but I have seen that you are built to survive on even the roughest parts of the journey. I also know that truth will out in the end...with posterity eventually giving credit where credit was due. For the past few years, I've mostly just been watching you "enjoy the ride"...still am I guess...but in the future, I'm hoping to accompany you on a few side excursions along the way.

Keep writing, Sir. Keep writing...

This is indeed one of my favourite arguments - and I'm still finding myself having to digest it every time I come across it. There's just so much information! Fantastic as always