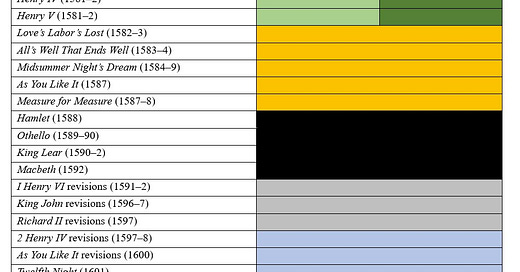

… In contrast, the actual chronology of North’s source plays progresses organically and fits the mold of identifiable authorial periods, all influenced by the events of his life and the works he translated.

My recent post “Explaining the First Folio” was one of my most successful ever:

And I want to welcome and thank all the new subscribers to “All the M…