The Two Most Rugged, Heroic, Death-Defying Survival Stories Ever

Both involve penguins

Endurance

On May 20, 1916, Sir Ernest Shackleton and two of his crew staggered into the whaling station at Stromness on South Georgia Island, just north of Antarctica. Their clothes were mere rags, and their faces were weather-beaten and black with frostbite. The Norwegian whalers stared at him and his two exhausted crewmates in astonishment. One man whispered, “Who the hell are you?”

“My name is Shackleton,” he replied. And so ends one of the most legendary survival tales in history.

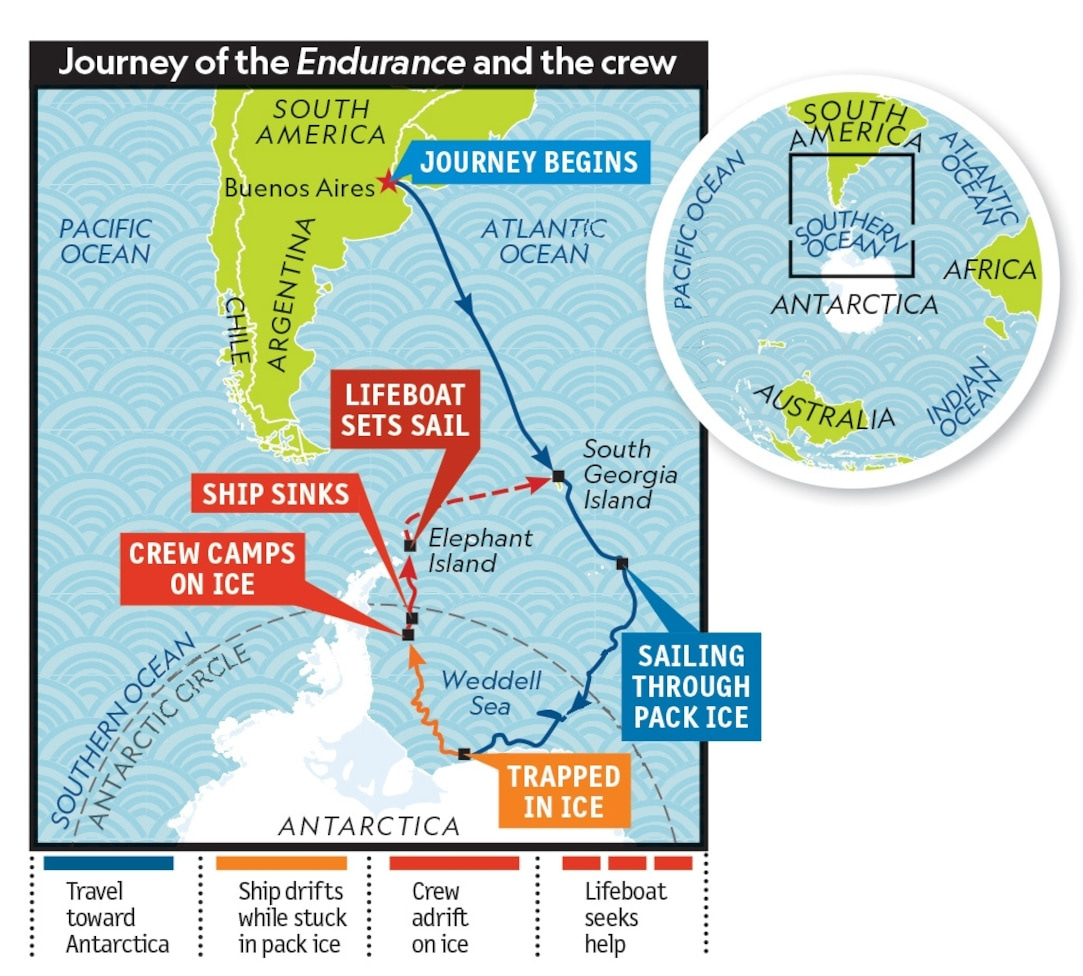

The story began 18 months earlier, in 1914, when the Anglo-Irish explorer Shackleton set out to accomplish what no one had before: the first land crossing of Antarctica. He and his 27-man crew never even got past the coast. Shackleton’s ship, aptly named The Endurance, became ensnared in the pack ice of the Weddell Sea and was eventually crushed, leaving them stranded in the most hostile environment on Earth.

Over the next 18 months, Shackleton then led what may be the greatest survival effort in the history of exploration. With no hope of rescue, the crew camped on drifting ice floes, living off penguins, seals, and their sled dogs. Penguin-steak with a side of seaweed, in particular, became their breakfast, lunch, and dinner. When the ice beneath them began to break up, they launched three lifeboats and spent a brutal week at sea before landing on the uninhabited Elephant Island, just at the tip of Antarctica.

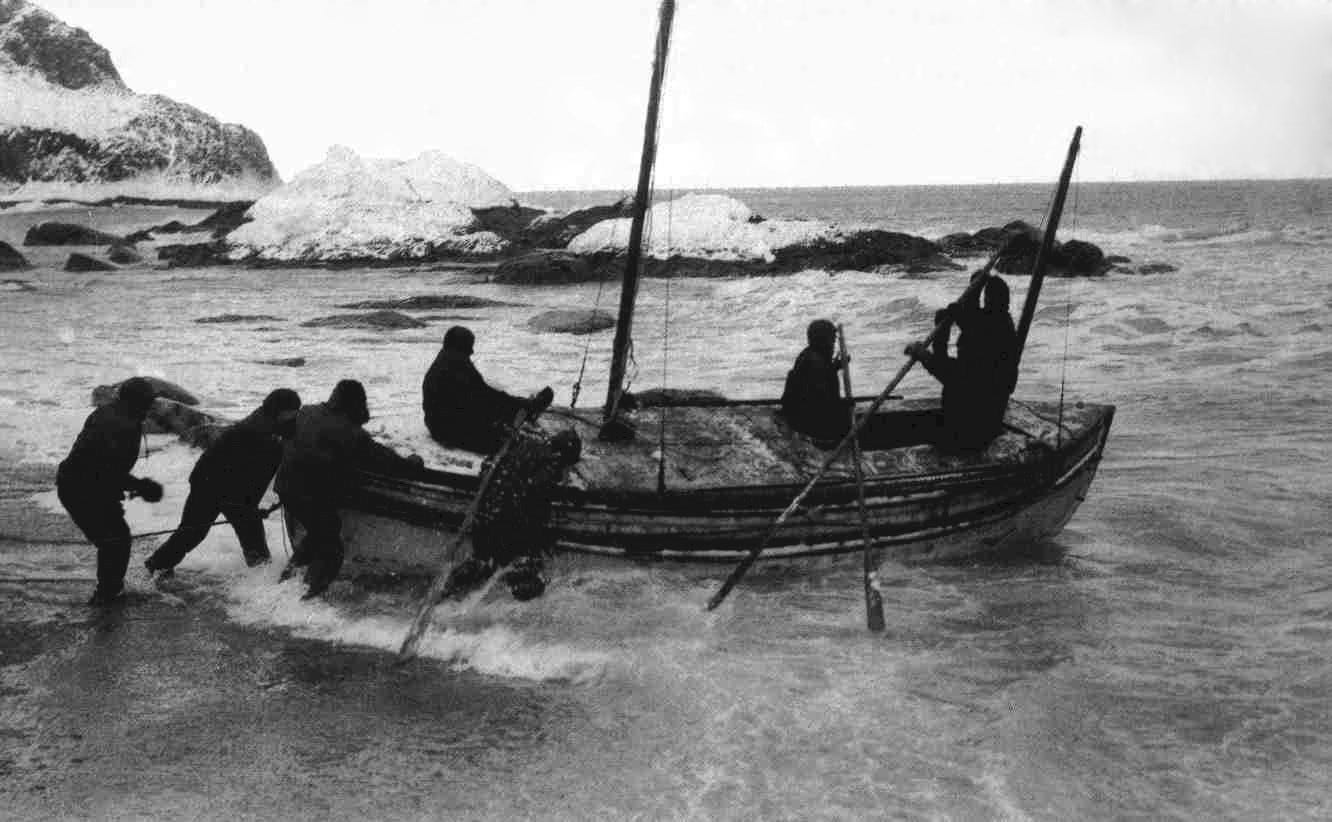

From there, Shackleton and five others set out on a 22-foot wooden lifeboat, the James Caird, and sailed 800 miles through the stormy Southern Ocean to reach the whaling stations of South Georgia. That, in and of itself, was one of the most perilous open-sea voyages ever attempted.

But their problems were not over. Stormy conditions had forced the six sailors to land on the wrong side of the island. So Shackleton, along with two men, then hiked for 36 hours nonstop—without maps or proper gear—over uncharted, mountains to reach the Norwegian whaling station at Stromness.

It then took Shackleton more than four attempts and three months to fight through the sea ice and retrieve the 22 men left behind. But on August 30, 1916, Shackleton returned to Elephant Island—and every man was still alive.

Shackleton’s remarkable high agency and unyielding perseverance under impossible conditions have ensured his expedition's place in history. But in the annals of survival, it can only rank second.

The Greatest Story of Survival Ever

In an earlier post, I wrote about the system of volcanic spreading ridges that formed around Antarctica and broke up Gondwana:

The Volcanoes that Killed a Continent, Shaped Civilizations, and Transformed the World

If I had to point to a single geological feature of the Earth that had the greatest consequence on life in the post-dinosaur world, that is, on our entire global ecosystem as encountered today, I would choose the undersea volcanic spreading ridges that presently encircle Antarctica. This little-known ring of cracks in the ocean bottom has drastically i…

Perhaps, the most obvious biological consequence of the development of the circum-Antarctic ridge is also the most disturbing. As the surrounding ridge systems steadily isolated Antarctica, all of its non-flying and non-marine animals became trapped on a continent that was about to be overtaken by one of the most destructive forces in Earth-history: ice.

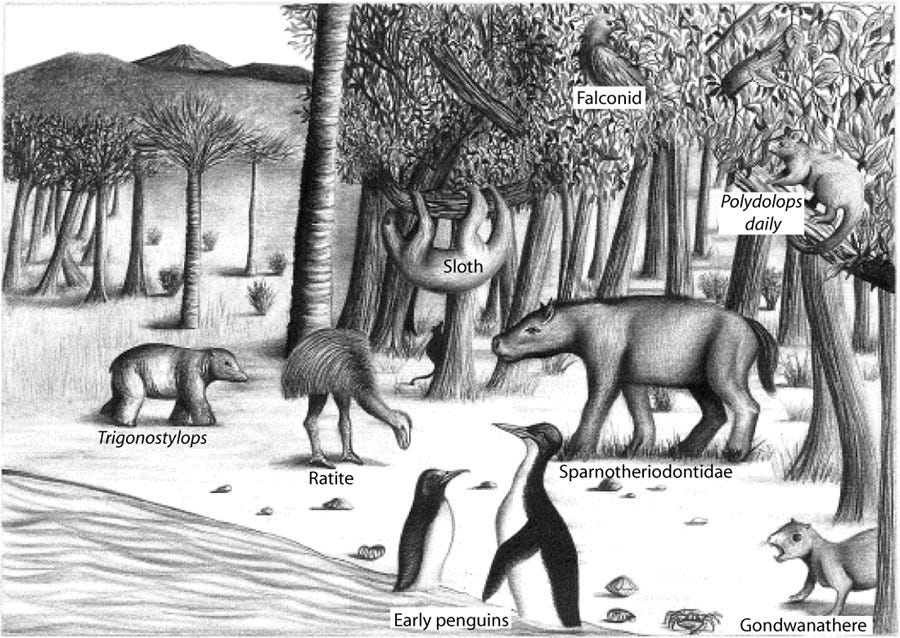

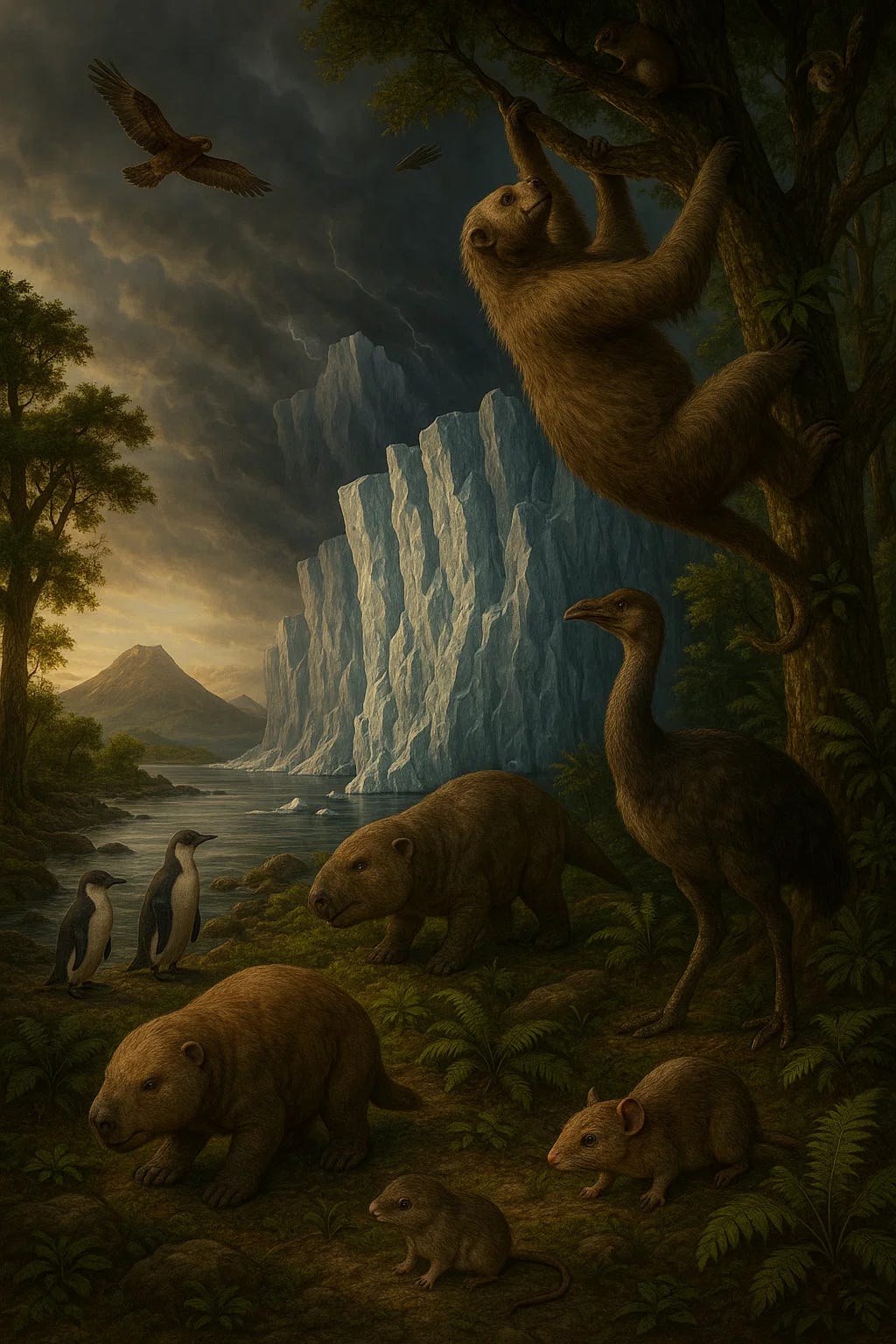

Many people tend to think that the current state of the poles, with Antarctica smothered beneath three kilometers of glaciers, as “natural” —as if the continent has always been so frozen. The truth is that for much of the last 250 million years, the Earth was usually much hotter than it is now—often with little to no year-round ice anywhere. During one of Earth’s warmest points, around 50 million years ago, London had an average temperature of 25°C (77°F), and it had tropical forests—as did Montana. The very high latitudes during this time have been described by the geologist Donald R. Prothero as "the palmy balmy polar regions,”1 and Ellesmere Island in the northern-most section of Canada, deep within the Arctic Circle and adjacent to northern Greenland, was home to turtles, salamanders, and alligators. Ellesmere had a climate similar to what we might find in the middle of the United States today. Antarctica, too, was a thriving, temperate forested ecosystem—even though it was pretty much in the same place where it is now. The fauna of the Antarctic Peninsula of the mid-Eocene (perhaps around 40 million years ago) was very much like that of southern South America at the time, with a great number of birds, including large, flightless ratites, perhaps similar to the rheas of South America today, and penguin-ancestors, which were quite comfortable in the mild weather, having not yet adapted to the brutal cold. A healthy variety of mammals also roamed these Antarctic forests, including large hoofed animals, sloths, and numerous kinds of marsupials.2

Since climate is such a chaotic system consisting of innumerable variables, we do not yet understand why the globe started cooling so significantly at the end of the Middle Eocene (~37 million years ago) and, again, at the “terminal Eocene event” (~ 34 million years ago), when the world abruptly went from greenhouse to icehouse. Many factors have been suggested including declining levels of carbon dioxide. But climatologists believe that one of the most significant factors was the final separation of Australia—and specifically the South Tasman Rise—from Antarctica. It was then and there that the seafloor spreading ridges completed the circle around the Southern continent, allowing the development of the Circum-Antarctic current system and greatly decreasing oceanic transport of warm waters to the southern continent. Surface water temperatures around Antarctica dropped by as much as 8°C (14 - 15°F).

And that was when the glaciers started to come.

As far as we are aware, at a continental level, nothing has been so efficiently destructive, so indiscriminately murderous, as ice.

Figure: Antarctica, ~40 million years ago, not long before the ice (Adapted from Reguero et al., 2002)

The truth is that emperor penguins provide the single most gripping example of rugged survivalism, perhaps in the entire history of back-boned creatures.

In terms of number of species lost, the Earth has faced far more devastating crises—particularly the global extinction events that marked the end of the Permian and Cretaceous eras. But on a continent-wide level, in terms of percentage of species killed and never replaced, perhaps nothing can compare to the Antarctic catastrophe—not meteors, not supervolcanoes, not the evolution of humans. As far as we are aware, at a continental level, nothing has been so efficiently destructive, so indiscriminately murderous, as ice.

After hundreds of millions of years of liveliness and greenery, Antarctica in a very brief period at the end of the Eocene became an icy, barren wasteland. Antarctica is much colder than the Arctic because the latter sits atop an ocean—a massive and dense heating system that never drops below 0°C (32°F.) Antarctica, by contrast, is a frozen block of land, far too cold to support the relatively diverse mammals that inhabit the icy north. Today, the temperatures of Antarctica in the winter are similar to the surface of Mars—and it seems every bit as inhospitable. It is the highest, driest, coldest, and windiest of continents. And what complex life it does support, the few plants and simple insects like springtails and mites, must cling to the ice-free tips on the margins of the continent and some rocky regions in East Antarctica. The continent is roughly the size of the United States and Mexico combined, but less than 1% of it is currently available for plants to take hold. It has no trees or shrubs and only two flowering plants: pearlwort and hair grass. The other plants are typically the ground-hugging ones that are best equipped for extreme environments, like mosses and lichens. There are some ice-free regions in different parts of the Antarctic interior, where the dry conditions and lack of snowfall prevent glaciation. But these so called “dry valleys” harbor almost no terrestrial creatures at all except for the little roundworm nematodes, which feed off bacteria and yeast. The food chain of these barren regions is, as far as we can ascertain, the simplest on the planet, and nowhere else is the soil so poor in ecological diversity.

While Antarctica may often be striking to look at in pictures, when the summer sun brightens the ice, we should not forget that beneath the ice sheets is a continent-wide bone-yard. The notorious end-Cretaceous extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs, though it did occur globally, did not have as devastating an effect on any particular continent as did the slow spread of glaciers on Antarctica. At the end of the era of dinosaurs, roughly 65 - 85% of all species perished, but the suppression of biodiversity did not last long, and the gain in mammal and bird species helped offset the loss of dinosaur species. But this was not true in Antarctica. Its isolation and freezing simply brought to that continent an endless death—taking more than 99% of all its species. One understands the fascination and reverence that geologists and climatologists have for the austerity and blistering ruggedness of Antarctica, but I suspect that not a few biologists sympathize more with the view of Robert Falcon Scott, the British explorer who reached the South Pole in 1912. "Great God, this is an awful place,” he wrote just before he succumbed to cold and starvation, along with the rest of his team.

The truth is that emperor penguins provide the single most gripping example of rugged survivalism, perhaps in the entire history of back-boned creatures.

A more realistic view of the ice caps now smothering Antarctica also helps us to reassess our perception of its most famous denizen—the emperor penguins. It is tempting to look at these swimming birds as little tuxedoed, half-ridiculous waddlers, happily frolicking in a winter wonderland. But their cute awkwardness on land not only gives their homeland a misleadingly benign appearance, it overshadows the penguins’ most significant attribute—their almost inconceivable tenacity. The truth is that emperor penguins provide the single most gripping example of rugged survivalism, perhaps in the entire history of back-boned creatures. They are the only remaining hold-outs of the diverse year-round vertebrate fauna of the Antarctic Eocene. As all the other native creatures continued to fall before the advance of the glaciers, as all of the Antarctic placentals, marsupials, reptiles, birds, and freshwater fish went extinct, the ancestors to the emperor penguins continued to adapt and persist. In contrast to the Disney-like view of the emperor penguins, we should see them for what they really are: the stressed and brutalized victors of the largest and most vicious game of survivor in the last 60 million years. In the dead of winter, on the entire mainland continent of Antarctica, they are now all alone—the only creature left standing.

The keys to their survival included both physical adaptations—like their layer of blubber, dense coat of feathers, and large size, all of which help to retain heat—and an array of complex sociobiological innovations. The old saying that “it takes a village to raise a child” is really true for the penguins, which rely on the entire colony to get their eggs and chicks through the winters. As the cold season approaches, the penguins travel away from the sea and deeper into Antarctica to breed and lay their eggs—sometimes as far away as 200 kilometers. They have to reach ice that will not break apart beneath their chicks during the warmer season before they are ready to swim. In May, after each mother has laid a single egg, they transfer it quickly over to the father, who carries the egg on his feet and protects it from the cold with a fold of skin on his belly. For two mostly dark months, the fathers endure the Antarctic winter incubating the egg, while the mothers, who have invested so much energy in producing the eggs, return to the sea to fatten up on fish, krill, and squid.3

The emperor penguins have developed a close herding instinct—and are the only penguin species that is not territorial. During the brutal winter blizzards, when temperatures can drop to -40° C (which is also -40°F), the father penguins, eggs on feet, will huddle together for warmth, sometimes for days. The penguins steadily shift positions during their huddling, so that no penguin is exposed for too long on the outside of the group. The eggs hatch in mid-July, right about the time the mothers return with food in their crop for the new chick. Counting the original trek and courtship, the male emperors have now lasted for four months without food and have lost half their body weight. They soon head back to the sea, refuel, and return again to help tend the chicks. The mother and father thus take turns, trudging back and forth from the sea to the chick, helping the young penguin grow and build strength. We often look at various behavioral adaptations as merely helpful nudges, as traits that help bestow a selective “advantage” on some individuals and so start to become widespread through the population. But with the emperor penguins, this complicated suite of urges and instincts was indispensable to their survival. Without the development of the intense sacrifice of both parents and the full cooperation of the huddling penguin colonies, they almost certainly would have become extinct—just as everything else around them did.

So while we tend to think of penguins as naturally cold-weather creatures, the truth of the matter is that they were forced to endure the advance of the ice—and the process was merciless.4

Donald R. Prothero (1994) “The Eocene-Oligocene Transition: Paradise Lost,” Columbia University Press, p. 16.

M. A. Reguero, S.A.. Marenssi, and S. N. Santillana (2002) "Antarctic Peninsula and South America (Patagonia) Paleogene terrestrial faunas and environments: biogeographic relationships," Palaeogeography-Palaeoclimatology-Palaeoecology, 179 (3-4), pp. 189–210.

The harsh wintering of emperor penguins can be seen in the stunning French documentary, March of the Penguins (2005), which received a well-deserved Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

This post is adapted from a chapter in "Here Be Dragons"