Why "Probability Zero" is Wrong About Evolution

How a best-selling anti-evolution book misuses mathematics and spreads misinformation

I believe this is one of my more important posts—not only because it explains evolution in simple, intuitive terms, making clear why it must be true, but because it directly refutes the core claims of Vox Day’s best-selling book Probability Zero: The Mathematical Possibility of Evolution by Natural Selection. Day’s adherents are now aggressively pushing its claims across the internet, declaring evolution falsified. As far as I am aware, this post is the only thorough and effective rebuttal to its mathematical analyses currently available.

This topic is also firmly in my wheelhouse. I have published multiple peer-reviewed papers on evolution and biogeography, and the subject was the focus of my first book: Here Be Dragons: How the Study of animal and plant distributions revolutionized our views of life and Earth (Oxford University Press, 2009). While reviews of that book were generous—The Huffington Post wrote: “At the end of the book you will be someone different;” and Science Magazine declared “we will never look at the world in the same way again”—it never achieved the extraordinary sales or global advocacy of Population Zero.

That disparity points to a larger problem. We live in a world where myths and falsehoods often drown out sober, evidence-based truths. And we know why: purveyors of misinformation are often far more energized, more confrontational, and more relentless than those committed to accuracy and reflection. If you want to push back against that imbalance—if you want to resist the spread of loud and confident error—please like, restack, or share this post.

Currently, the number one best-selling book on evolution is a book that claims to have falsified it: Probability Zero. It was written by the uber-controversial Vox Day, whose author page describes him thusly:

Six-time Hugo Award finalist Vox Day writes epic fantasy as well as non-fiction about religion, political philosophy, and economics. He is a multi-platinum-selling game designer who speaks four languages and a three-time Billboard Top 40 Club Play recording artist.

Public denunciations of Vox Day’s political views or ideological associations are easy to find, but they are irrelevant to the present analysis. He is clearly intelligent, and Probability Zero, though wrong, contains nothing remotely disturbing or objectionable. The book deserves to be addressed on its own terms. So—here we go.

First, to be clear: evolution is, at bottom, remarkably simple. It rests on a few basic premises that virtually everyone—including creationists—already accepts. Everything else inexorably follows:

Premise 1: Variation:

Members of the same species differ in countless ways—size, strength, coloration, speed, physiology, behavior, disease resistance, morphology, etc.

Premise 2. Heredity:

All organisms pass on their traits to their offspring—but their offspring are not duplicates. Indeed, even clones will occasionally have mutations.

Premise 3: Differential Survival and Reproduction.

Some traits help certain individuals to survive and reproduce more frequently than others. Resources are finite and danger, ever-present. Predators, disease, climate, accidents, and competition ensure that some individuals leave more descendants than others.

Given these premises, evolution is certain.

That’s it. That’s all you need. If individuals differ, and if those differences affect survival and reproduction, then the traits carried by the more successful individuals will become more common over time. No additional assumptions are required. No philosophical commitments. No speculative leaps. Evolution has to happen.

Also, Darwin’s theory doesn’t necessarily require speciation. Evolution is simply the transformation of organisms by the accumulation of changes over generations. Or, as a corollary to that, we could describe evolution as the process by which genes steadily become more frequent or infrequent throughout the gene pool over generations.

Ironically, Probability Zero includes many excellent descriptions of evolution in action. For example, in the following, Day explains how a single mutation promoting persistent lactose tolerance in North Europeans spread to 80%-90% of its population:

The lactase persistence mutation provides an even more instructive example because it offers a much longer timeline. Lactase is the enzyme that digests lactose, the sugar found in milk. In most mammals, including most humans throughout history, the gene that produces lactase is downregulated after weaning, making adults lactose intolerant. However, in certain human populations—particularly those with a history of pastoralism and dairying—a mutation arose that allows continued lactase production into adulthood.

The primary European lactase persistence allele (LCT-13910*T) is estimated to have arisen approximately 7,500–10,000 years ago, coinciding with the advent of dairying in Neolithic Europe. This mutation confers a significant nutritional advantage in cultures that practice animal husbandry, as it allows adults to digest milk—a rich source of calories, protein, fat, and calcium that would otherwise cause gastrointestinal distress.

Well done. But this startling increase in gene frequency of a mutation that confers a survival advantage is indeed an example of evolution—and is described as “the evolution of lactose tolerance.” As clear, many who argue against evolution fixate on its most dramatic outcomes—such as speciation—while overlooking the fact that they already accept countless mundane examples of evolution. They readily acknowledge that small changes occur within populations, yet fiercely resist the obvious implication: that the sustained accumulation of those small changes, generation after generation, inevitably produces increasing divergence and diversity.

To give a quick idea of what is possible through selection (and I know this is not an example of natural selection—but human selection), consider a toy poodle, a dachshund, and a wolf as examples of how much a species can indeed transform in just a few thousand years. And these great changes were brought about simply by sustained selection acting on existing variation. The only difference between directed evolution of dogs and the natural evolution of wild species is not whether selection operates, but who does the selecting—humans in one case, the environment in the other.

Also—and this cannot be stressed enough—the selective pressures imposed by the environment are neither persistently mild nor merely random or chaotic. Events such as desertification, glaciation, sea level rise, or the sudden arrival of new predators can impose brutally strong selection for thousands or even millions of years, producing highly predictable outcomes. After all, what is the difference between a dog breeder selecting for a thick, woolly coat to survive cold climates and the Last Glacial Maximum doing the same? This harsh planet relentlessly rewards traits that work—deeper roots in drought, speed or camouflage under predation, resistance to disease—and just as relentlessly eliminates those that do not.

Finally, there is no brake—no invisible wall—that arbitrarily halts adaptation after some prescribed amount of change. Small variations accumulate without limit. Generation after generation, those increments compound, and what begin as modest differences become profound transformations. When populations of the same species are separated by an earthly barrier—a mountain, a sea, a desert—they diverge: first into distinct varieties or subspecies, and eventually into separate species. And precisely what this process predicts is exactly what we find. Everywhere, without exception.

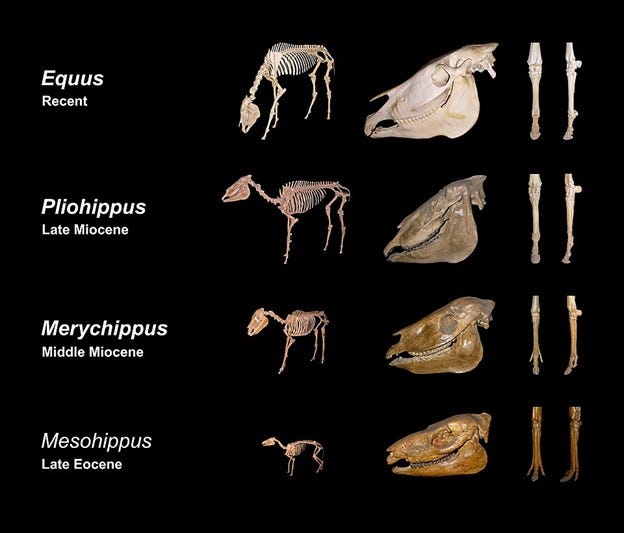

How does Probability Zero challenge this? It doesn’t. How could it? The book is first and foremost what I like to call an end-around. It does not present a systematic attack on the facts just presented—or, for that matter, any of the vast body of empirical evidence that confirms evolution. It sidesteps entirely the biogeographical patterns that trace a continuous, unbroken organic thread that runs through all regions of the world, with the most closely related species living near each other and organic differences accruing with distance; the nested hierarchies revealed by comparative anatomy and genetics; the fossil record’s ordered succession of transitional forms (see pic); directly observed evolution in laboratories and natural populations; the frequency of certain beneficial traits (and their associated genes) in human populations, etc.

Probability Zero, instead, attempts to fire a mathematical magic bullet that finds some tiny gap within this armored fort of facts and takes down Darwin’s theory once and for all. No need to grapple with biology, geology, biogeography, fossils, etc., the math has pronounced it “impossible,” so that ends that.

Probability Zero advances two principal mathematical arguments intended to show that the probability of evolution is—as its title suggests—effectively zero. One centers on the roughly 20 million mutations that have become fixed (that is, now occur in 100% of the population) in the human lineage since our last common ancestor with chimpanzees roughly 9 million years ago. Chimpanzees have experienced a comparable number of fixed mutations.

Day argues that this is impossible given the expected number of mutations arising each generation and the probability that any particular neutral mutation reaches fixation—approximately 1 in 20,000, based on estimates of ancestral human population size. Beneficial mutations do have much higher fixation probabilities, but the vast majority of these ~20 million substitutions are neutral. As Day writes (emphasis added):

The human genome experiences approximately 100 new mutations per individual per generation. With an effective population of 10,000—a common estimate for ancestral human populations—that’s roughly 1 million new mutations entering the population per generation, or about 50,000 per year. Over 9 million years, the human lineage needed to fix 20 million mutations.

That’s approximately 2.2 successful fixations per year. If 50,000 mutations arise per year and 2.2 need to succeed, the required success rate would be one in 23,000, or 0.004%. But what is the actual probability of fixation under Kimura’s model? For a neutral mutation, and Neo-Darwinists themselves insist that the vast majority of mutations are neutral, the probability of eventual fixation is 1/(2N), where N is the effective population size. For N = 10,000, that’s 1 in 20,000. This probability already accounts for the fact that most mutations are lost to genetic drift in the early generations; it is the total probability that a new neutral mutation, appearing in a single individual, will eventually spread to the entire population. ….

Now we can calculate.

For the human lineage, the probability of 20 million independent fixation events each succeeding with probability 1 in 20,000 is:

(1/20,000)20,000,000 = 10−86,000,000

For the chimpanzee lineage, the calculation is the same—they also need 20 million successful fixations: (1/20,000)20,000,000 = 10−86,000,000

Since these are independent events—the human lineage fixing its mutations has no effect on the chimpanzee lineage fixing its mutations—we multiply the probabilities to get the combined probability of the complete divergence:

10−86,000,000 ⋅ 10−86,000,000 = 10−172,000,000

To put this number in perspective: the number of atoms in the observable universe is approximately 1080. The number of seconds since the Big Bang is approximately 1017. The probability we have just calculated is not merely small—it is smaller than any quantity that has physical meaning. It is, for all practical and theoretical purposes, zero.

Probability Zero then includes pages describing how vanishingly small this chance is, cheekily labeling the denominator number, “One Darwillion.”

“The Verdict The divergence of humans and chimpanzees from a common ancestor by means of random mutation, natural selection, and genetic drift is not improbable. It is not unlikely. It is not a close call that could go either way depending on how you interpret the evidence.

It is mathematically impossible.

The probability is one in one Darwillion. That’s not a number that allows for doubt. That’s not a number that invites further research to investigate the question. That’s not a number that should induce the optimistic to ask: “so what you’re saying is there’s a chance?” That’s a number that closes the door on the Modern Synthesis permanently, definitively, and irrevocably.

Here is the problem: What Vox Day calculated—(1/20,000)20,000,000 —are the odds that a particular group or a pre-specified list of 20 million mutations (or 20 million mutations in a row) would all become fixed. In other words, his calculation would only be accurate if the human race experienced only 20 million mutations in total over the last 9 million years—and every one of them then became fixed. And, yes, hitting a lottery (with odds 1/20,000) 20 million times in a row would indeed essentially be probability zero.

But our evolutionary history does not require that an exact group of 20 million mutations become fixed—only that some 20 million out of an enormous pool of candidate mutations become fixed.

Here’s the correct analysis. Using Vox Day’s numbers, in a population of 10,000 humans, we would expect, on average, 50,000 new mutations per year. And over the course of 9 million years, this means we would expect:

50,000 x 9 million = 450 billion new mutations altogether.

So out of 450 billion mutations, how many mutations may we expect to achieve fixation? Well, as Vox Day noted, each mutation has a probability of 1/20,000 in becoming fixed.

450 billion x 1/20,000 = 22.5 million fixed mutations.

And that is a pretty close approximation to the 20 million fixed mutations that have been observed. Change the assumptions1 and the estimate moves. But under Vox’s own assumptions, the result is the opposite of “probability zero”: it’s basically what you’d predict

Probability Zero’s other major mathematical proof against evolution involves a laboratory experiment on E. Coli bacteria. Quoting:

The fastest laboratory observed rate of mutational fixation comes from a 2009 study published in Nature, which sequenced 19 whole genomes of Escherichia coli bacteria and detected 25 mutations that were fixed over 40,000 generations. This yields an average of 1,600 generations per fixed mutation.”

And since Vox Day thinks this is the fastest possible rate of mutation fixation, he believes that places a concrete ceiling on the number of fixed mutations we should expect to occur over the 450,000 generations of humans since the chimp/human divide:

“The math is not hard. 450,000 generations divided by 1,600 generations per mutation equals 281.25 total fixed mutations.

And 281 is less than the 20,000,000 required.

A lot less. And that, in a nutshell, is the Mathematical Impossibility of The Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection, or, if like a good scientist you prefer jargon-friendly acronyms, MITTENS.”

Unfortunately, this analysis is flawed from the jump: E. coli does not exhibit the highest mutation rate per generation; in fact, it has one of the lowest—orders of magnitude lower than humans when measured on a per-genome, per-generation basis. One major reason is genome size. The human nuclear genome contains approximately 3.1 billion base pairs, roughly 690 times larger than the compact E. coli genome of about 4.6 million base pairs. Since human beings have so much more DNA to copy, there’s inevitably more typos. Every newborn averages 60 to 100 de novo mutations. In contrast, E. Coli produces an exact, mutation-free clone over 99.9% of the time, with one mutation occurring every 1000-2400 divisions.2

Indeed, the very research paper that Vox Day uses stresses this point, explaining why it is not even unreasonable to expect “that no synonymous mutations fixed in the first 20,000 generations.”3 This, again, is due to the small genome size and mutation rate of E. Coli.

As clear, the expected rate of fixed mutations has to be determined according to the particular circumstances of the population in question—its genome size, mutation rate, population size, etc. And as shown above, that calculation has been done for humans—and the observed 20 million fixed mutations are not surprising.

Finally, the author’s confusion likely lies in the fact that evolutionary theorists often speak informally of the speed of evolution in organisms used in lab tests—whether bacteria, fruit flies, etc. But that refers to the brief time in which these organisms can produce many generations—for example, the 40,000 generations in roughly 20 years for the E coli bacteria. But that doesn’t mean they experience a high rate of fixed mutations per generation. In fact, it’s just the opposite.

Coda: An Ode to Biogeography and Evolution (From Here Be Dragons)

The British geneticist J.B.S. Haldane once famously said that he would give up the theory of evolution if a fossil rabbit were found in the Precambrian. Haldane’s quote shows, in an understated way, just how constraining the predictions of the evolutionary view really are. The theory requires the general emergence of organic complexity from simpler systems in a relatively predictable way—single-celled organisms, multicellular creatures, then aquatic vertebrates, all followed by the first lung-fish-like creatures that crawled onto the land. This, in turn, had to precede the appearance of primitive four-legged terrestrial vertebrates and their eventual division into amphibians, reptiles and mammals. Only after the first appearance of mammals could we expect to see the emergence of primitive fossil rabbit forms and finally modern rabbits. That the chronological order of fossils, implied by stratigraphic layering and reconfirmed by radiometric dating, should so precisely match the chronological order necessitated by evolution can be no coincidence.

Just as evolutionary processes require a continuous genetic flow through time, with no inexplicable disjunctions, those same processes also require a continuous genetic flow through space. For a botanical metaphor that may help enliven this perspective, we may imagine, instead of the tree of life drawn alone on a blank page, an intricate system of creeping ivy steadily extending and branching over the surface of the globe, tracing with its myriad stems the divergent lines of descent through continents and oceans. Two of the stems of this unifying global ivy, corresponding to a couple of primitive marsupial lines, would extend into Australia and divide into nearly 200 branches representing kangaroos, koalas, bandicoots, and all the pouched animals down under. In South America, we could trace a lone stem for Darwin’s finches running from the coast into the Galápagos Archipelago and there splitting into thirteen branches that extend among the different islands. As all the stems and branches of this symbolic plant must remain whole and return to the same root, we can get an idea of what is and is not biogeographically feasible, helping provide distributional analogues to that impossible Precambrian rabbit.

To cite a few examples, biogeographers could say, with similar Haldane-like boldness, that we would give up the theory of evolution if anyone discovered giraffes in Hawaii or fossil kangaroos in Spain or another group of Galápagan iguanas in Lithuania, each of which would represent an unacceptable spatial disjunction – a rend in the evolutionary creeping ivy that would be every bit as problematic as the temporal disjunction described by Haldane. As with the chronological order of fossils, the continuous genetic flow of evolution so constrains the possible locations of plants and animals and allows so many opportunities for falsification that we may disregard any theory that cannot explain why organic distributions, all over the globe, should so persistently conform to such a faultless hereditary structure. The fact is that no theory other than evolution can describe how the creeping ivy of organic descent could so envelop the planet yet always remain whole. …

As he traveled around the world, Darwin was able to observe this same geographical current of organic relationships, running from region to region. Today, such patterns are obvious to those who know to look for them: They confront us frequently and perpetually throughout the normal course of our lives, helping distinguish biogeography from nearly all other subjects. Most of us do not typically encounter fossils or observe the workings of embryology or come across many of the other well-known indications of evolution. Nor do we often meet with reminders of the efficacy of other scientific theories, say, plate tectonics or the molecular theory of gases or Maxwell’s theory of the electromagnetic field. Most scientific models and principles follow from facts that require specialized knowledge and have been determined through careful investigation. But the distributional consequences of evolution are visible to practically everyone just through casual observation. Darwin noted in his summarial chapter in Origin of Species that some of the biogeographical facts he detailed “must have struck every traveler.” But consider the effect such observations would have on those already familiar with his arguments. No evidence will ever fetch the true believers, but the probative value of distributions may at least help enlighten a few now bewildered by the intelligent design debate. To people familiar with biogeography, every visit to a national park or vacation in the Caribbean or hike in the mountains will continue to provide new and vibrant testimony to the Darwinian bond between life and Earth. The theory of evolution thus no longer remains distant and abstract; it becomes integrated into one’s world-view in the same visceral way that the mechanics of anatomy become a part of a surgeon.

As the facts of heredity demand, all organisms on this planet are physically linked through a material stream of genes that has flowed without interruption for billions of years from a single ancestral source. Those who truly grasp this enjoy a world decorated by striking floristic and faunal patterns, all serving to illuminate the secret behind life and the grandeur of Darwin’s discovery. Those who deny evolution move through a fractured and irrational biotic world, devoid of organic relation and marked only by chaos and dim miracles. We should endeavor to close this gap. Biogeography, once a secret delicacy enjoyed only by geniuses, must now be elevated from its current obscurity and placed alongside literature and history as an indispensable component of a truly enlightened education.

This probability refers to neutral mutations, which do indeed describe the vast majority of mutations. However, beneficial mutations can, of course, spread across a population much faster than neutral ones.

For example, Sébastien Wielgoss, et al., write: “The resulting estimate of the point-mutation rate is 8.9 × 10−11 per bp per generation (Tukey’s jackknife 95% confidence interval, 4.0–14 × 10−11 per bp per generation). This estimate corresponds to a total genomic rate of 0.00041 per generation given the ancestral genome size of 4.6 × 106 bp.” See Sébastien Wielgoss, et al., “Mutation Rate Inferred From Synonymous Substitutions in a Long-Term Evolution Experiment With Escherichia coli,” Genes|Genomes|Genetics (2011), 1(3), 183–6.

Jeffrey E. Barrick, et al., “Genome evolution and adaptation in a long-term experiment with Escherichia coli,” Nature (2009), 461, 1243–1247.

I appreciate your critique of Probability Zero, Mr. McCarthy. I'll link to your post tomorrow morning and give everyone a day to contemplate your points for themselves before responding to it on Tuesday.

This is very interesting, and like Vox said. The first genuine attempt at a critique, smart. Not the usual "reddit-tier" garbage.

I'll give my short impression on the subject, I'm thinking Evolution is right in the aspect of noticing the patterns. The thing it gets wrong is the mechanism. Evolution by natural selection is wrong, but Evolution by other means? that's a different subject.

Anyhow this has been a good read and I'm definitely bookmarking the back an forth to keep reading in the future. Honestly, this exchange between you guys might merit a book in itself