How We Know Thomas North Wrote the Plays that Shakespeare Later Adapted

Free, sharable post that summarizes the proofs of North's original authorship

The brilliant Stetson—who is dashing in looks, thought, and name—authors a wide-ranging and important Substack, Holodoxa, for “the intellectually curious generalist,” which I highly recommend. His background is cancer, genetics, the genetics of cancer, and neurodevelopment, but like all lively-minded generalists, he is interested in anything, everything, and, most especially, the consilience of it all put together.

Stetson recently commented on my recent article/podcast (“Is Everyone Once Again Blindly Resisting a Modern Day Intellectual Revolution?”) that I had the opportunity to “specify the argument and present/analyze the available data differently/ comprehensively.” He is certainly right about that. The article that accompanied the podcast merely crammed in pics of tables involving just one particular type of evidence: unique passages, lines, and word-strings shared by North and Shakespeare. But the truth is I have yet to give a clear, comprehensive view of the theory on “All the Mysteries That Remain,” but this will change now. And of course, the most complete explanation of the North theory, complete with all the proofs and analyses appears in my book, Thomas North: The Original Author of Shakespeare Plays.

This summary is divided into five parts. The first is a quick intro on the North theory meant to help overcome initial skepticism, showing the ideas have passed peer review, resulted in discoveries that have shocked the world, do not invoke conspiracy theories, etc. Part two provides an overview of evidence for North’s authorship of Shakespeare’s plays. Part three lists smoking gun proofs of North’s authorship. Then we list the “Conclusion,” followed by Common Questions.

First, let’s suspend disbelief

The following four points all should help alleviate initial skepticism:

As all scholars agree, Shakespeare frequently adapted old plays. Yes, Shakespeare was a literate playwright who worked his quill in all the plays that were attributed to him, but we also know that Shakespeare frequently adapted earlier plays—a fact no scholar denies. Renowned editors and researchers have uncovered evidence for Shakespeare’s use of earlier plays in dozens of cases. Some of this evidence includes impossibly early allusions to seemingly “Shakespearean” plays from the 1560s, 1570s, and 1580s—too early for Shakespeare, who was born in 1564, to have written them. For example, the poet Arthur Brooke references a Romeo and Juliet he had seen on stage in 1562, two years before Shakespeare was born. Similarly, contemporaries of Shakespeare—and literary insiders in the decades after his death—repeatedly described Shakespeare as an adapter of old plays. (Finally, some of North’s plays still exist, including Arden of Faversham and True Tragedy of Richard III.)

Shakespeare scholar, June Schlueter, Professor Emerita of Lafayette College and former editor of the Shakespeare Bulletin, and I have already passed peer review, writing for academic presses, confirming Thomas North wrote early versions of three Shakespeare plays. In 2014, Schlueter and I published evidence in Cambridge’s Shakespeare Survey indicating that Thomas North wrote the original version of Shakespeare’s, Titus Andronicus. In 2021, Schlueter and I published our discovery of North’s travel-diary (and its use in the plays) in Thomas North’s 1555 Travel Journal: From Italy to Shakespeare with Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. The diary described a 20-year-old Thomas’s exotic experiences in Italy—a journey of wondrous events that the playwright would use as a well-spring for the most spectacular and memorable scenes of Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale. As Michael Dobson, Director of the Shakespeare Institute, wrote about the book: “McCarthy and Schlueter’s book will be compulsory reading in its turn for every scholar of these plays, and for anyone interested in Shakespeare’s reading.” And Patrick Buckridge, former Head of School of Humanities, Griffith University, and former co-editor of Queensland Review, wrote:

“McCarthy and Schlueter have once again produced evidence that ought to rock Shakespearean scholarship to its foundations.” —Patrick Buckridge

Those few outside intellects who have carefully studied the North view have been convinced at both the accuracy and significance of the discovery. Investigative journalist and The New York Times bestselling author of The Map Thief, Michael Blanding did a deep dive into our research and ended up writing a book on the North discovery: In Shakespeare's Shadow: A Rogue Scholar's Quest to Reveal the True Source Behind the World's Greatest Plays. In 2022, Blanding published an article on LitHub explaining that any prior questions about North’s authorship of Shakepseare’s source-plays have now all vanished. Blanding has now become our collaborator, and, as shown below, has made a few astonishing North/Shakespeare related discoveries himself. Likewise, the fierce realist, political expert, and author,

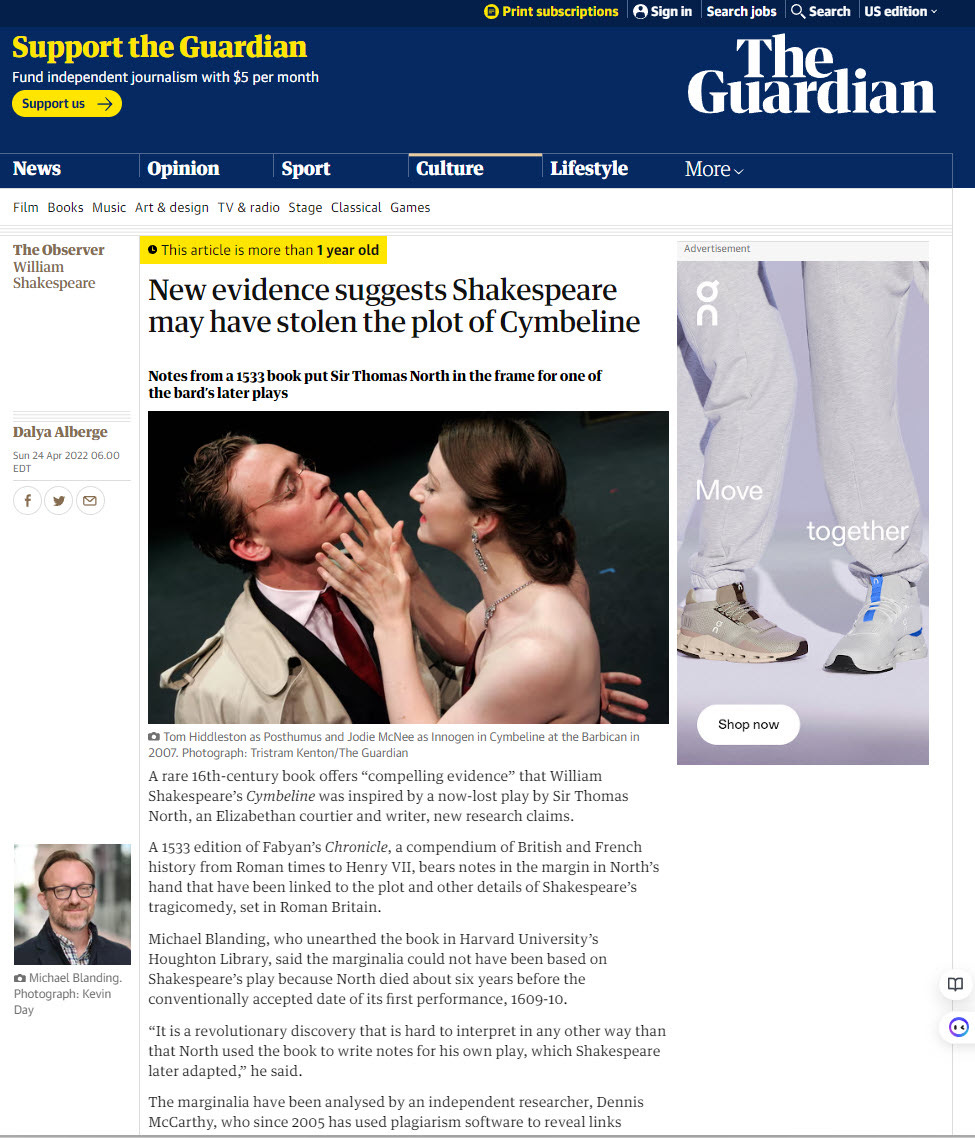

, has also read my book on Thomas North and was kind enough to invite me on his podcast:Knowing North had written Shakespeare’s old plays has led us to discover a treasure-trove of Shakespearean texts that have generated news reports around the world and praise from many top Shakespearean scholars. We have already mentioned Thomas North’s handwritten journal above. In the “Smoking Guns” section below, we discuss Blanding’s discovery of North’s marginal comments in a history book kept at Houghton Library, which turned out to be an outline to Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. News of this discovery made The Guardian:

Also, Schlueter and I published our discovery of a 1576 manuscript on rebellions— A Brief Discourse of Rebellion & Rebels: A Newly Uncovered Manuscript Source For Shakespeare’s Plays, (British Library, 2018)—formerly kept at Thomas’s family estates. George North, a likely cousin of Thomas, wrote the manuscript and made sure to compliment Thomas’s literary abilities in the foreword. Importantly, this handwritten work, with no known copies, was used as a source for eleven Shakespeare plays. News of the find made the front page of The New York Times, The (London) Times, The Telegraph, The Guardian, The Independent, The Daily Mail, The Los Angeles Times, U.S. News, Philadelphia Inquirer, and Slate.com, and generated still other press in France, Italy, Spain, Poland, Austria, Germany, Romania, India, Israel, China and elsewhere around the globe.

The late David Bevington, Professor Emeritus of the University of Chicago, editor of the Norton Anthology of Renaissance Drama, studied our work and wrote:

“New sources for Shakespeare do not turn up every day in the week. This is a truly significant one, that has not heretofore been studied or published. The list of passages in Shakespeare now traced back to this source is an impressive one… This is all a revelation to me, all the more remarkable in that this manuscript has been hidden and unexamined until now.” —David Bevington

One must wonder, if everyone agrees that Shakespeare adapted old plays, and we have passed peer review exposing evidence that North wrote a few of those old plays, then what is the problem?

Well, the problem is, as editors and academics soon found out, we didn’t just have evidence that North wrote a few plays of Shakespeare; we knew he had written essentially all of them. And such a discovery is extremely disruptive. It not only challenges conventional views of Shakespeare and his modus operandi, but upends a significant amount of previous work on the subject.

Yes, scholars knew that Shakespeare frequently adapted old plays, but they mostly ignore that fact when analyzing them. And no one ever suspected that the same person wrote all of the earlier source-plays and even based them on the most significant events of his life. Thus, the North discovery gives new meaning to the plays and places them in an entirely different political and personal context, making essentially all prior editions and collections of the plays inadequate or even obsolete.

How We Know North Wrote the Plays

With the theory of evolution, we not only have general evidence that indicates all organic species have evolved from simpler forms; myriad species also flaunt particular evidence, unique to themselves, helping confirm the veracity of evolution. Studies on the beaks of Galápagos finches; discovery of ring species such as the Ensatina salamanders, DNA studies on dogs and wolves, the fossil records of horses, etc., all provide independent evidence for Darwin’s famous discovery. Similarly, while various discoveries establish North’s involvement with the entirety of the canon, essentially every play includes a particular set of unique facts that also confirm North’s original authorship. Here we briefly summarize evidence for North’s general involvement.

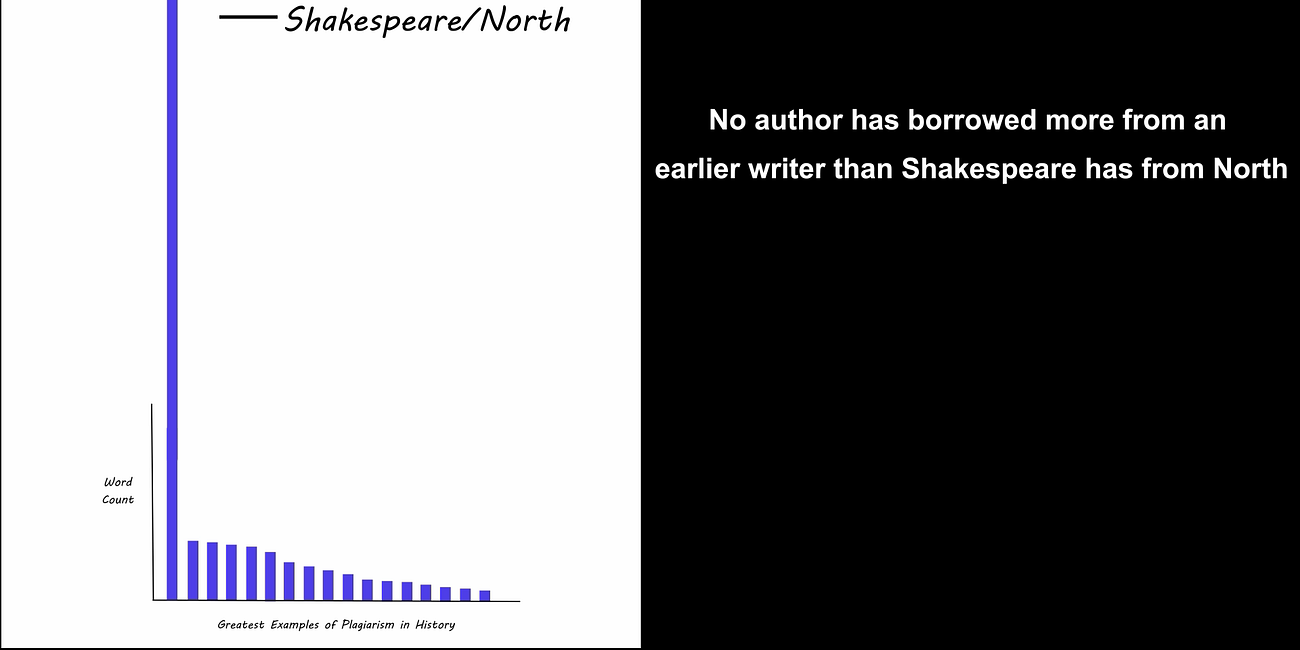

Shakespeare’s plays recycle thousands of lines and passages from North’s writings. When North wrote his plays, he frequently recalled and then recycled many of the stories, images, ideas, speeches, and characters from both his published and unpublished writings. He almost assuredly did this from memory, paraphrasing a passage or scene he had written about before — and in the process he would repeat the same language he used earlier. And many of these recycled passages still remain in Shakespeare’s adaptations. The result is that literally thousands of lines and passages in the Shakespeare canon can be traced back to North’s prose texts. These borrowed passages derive from everything North ever wrote and involve nearly every act of every play — not just the Roman tragedies. And many of the links between the passages cannot be disputed as they include identical lines that no one else in the history of English has used — not at the time and not since. Quite simply, as this video shows, no one has borrowed more from an earlier writer than Shakespeare has from North, and it is not even close.

The Mind Boggling Extent of Shakespeare's Borrowings From Sir Thomas North

·This video provides a just-believe-your-eyes moment. [Reproduced from an earlier post]

For an article (as opposed to a video) that reproduces many of these North/Shakespeare lines and passages, click here. The passages are reproduced in the article that accompanies the podcast, though I do read a list of a few of the shared lines in the podcast. Finally, as for the best way to present and discuss these thousands of North/Shakespeare verbal parallels on Substack, whether in an article, podcast, or video, I am open to suggestions.

Shakespeare’s Plays are Based on Thomas North’s Life. As shown in Thomas North: The Original Author of the Shakespeare Canon, the life and writings of North so persistently dovetail with the works later adapted by William Shakespeare that to follow North’s life in detail is to reconstruct the entire history of the Shakespeare canon, play by play and subplot by subplot. And this does not refer to the occasional coincidence linking some minor life incident with some trivial detail in a play. Every major aspect of North’s life and every shift in his experiences, whether traumatic or joyous, is reflected in the vicissitudes of his oeuvre. Individual plays are like temporary snapshots, capturing myriad peculiarities of his life circumstances, his friends, family, travels, and his involvement in Marian and Elizabethan politics at the time of its penning—while more significant life changes can be traced through more expansive literary periods. Numerous references and allusions heretofore deemed mysterious have now found explanation in North’s life history. Even more stunningly, the most iconic visual play from each play—essentially every set-piece scene—also comes directly from North’s life.

The satirists Ben Jonson, Thomas Nashe, and Thomas Lodge—all of whom are well known to have parodied contemporary playwrights—spoofed a well-traveled, Italianate knight-translator (whom we have identified as North) as the original author of Shakespeare’s plays. Schlueter and I have an article that will be published in 2025 confirming that the satirists were all targeting North and identifying him as the author of early plays later adapted by Shakespeare.

The Jigsaw-Like Chronological Fit of Both North’s Life and Writings with the Source Plays: Using independent evidence, we can firmly establish the date of dozens of early source plays, placing each of these earlier works on a timeline starting in 1556 and extending to 1604. And we can confirm that each play recreates the most significant moments of North’s life and combines them with material from his latest writings, including personal papers.

In other words, North’s plays from a particular period not only reflect what North had just experienced but also what he had just recently translated or written. All of North’s plays follow this same pattern, year after year, decade after decade. The plays overflow with the most important people, stunning visuals, and memorable moments of North’s life during the time he first wrote them—as well as the most remarkable stories and passages he had recently written in his translations or journal. The consilience of this evidence is truly astonishing and trying to dispute it would be like trying to deny the accuracy of every two-piece fit in a completed jigsaw puzzle in which all the pieces meet seamlessly and the image matches the picture on the front of the box.

Smoking Guns, Smoking Cannons, and Smoking Thermo-Nuclear Bombs

1) The playwright used Thomas North’s handwritten travel journal for Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale

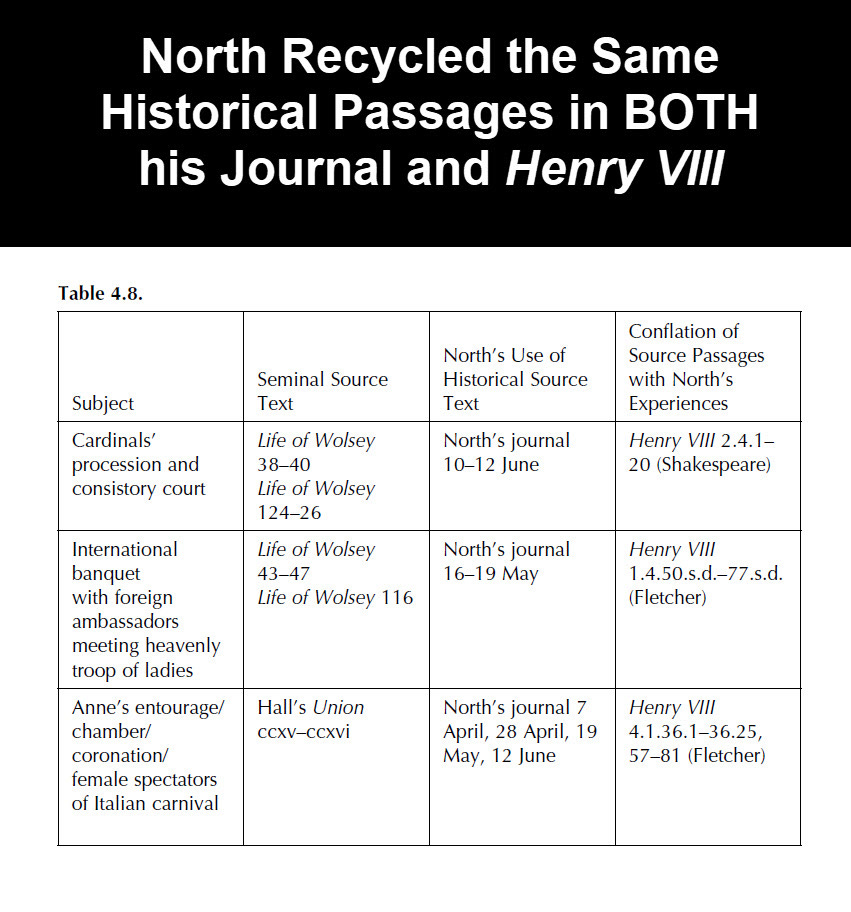

suggested a different type of presentation of data, especially involving parallel passages, and, like the video above, again this video does attempt that. It also serves to prove that North took experiences that he described in his handwritten, unpublished travel-journal and used them in Henry VIII. The video also shows why we may reject as an explanation the supposition that Shakespeare (or Fletcher, Shakespeare’s co-author of Henry VIII) may have gotten hold of North’s journal. For North not only recycled scenes from his journal in Henry VIII, he also took the same historical passages that he used in his journal and reused them in Henry VIII.

Quoting from Thomas North’s 1555 Travel Journal:

The result is that reading various entries throughout the journal gives the surreal impression that North, in 1555, somehow managed to experience the most spectacular events of Shakespeare and Fletcher’s Henry VIII.

Even assuming Shakespeare and Fletcher somehow got hold of the unpublished travelogue—and for some reason wanted to reproduce its visuals—we are stuck with the even more important question of “How?” How, without the use of digital technologies, would either have been able to determine what source passages the young journalist had used for his entries—some of which include a mix of widely separated elements—so that they could then make sure to conflate these same passages in their play? They couldn’t. It was North who had carefully studied these scenes in Cavendish’s Life of Wolsey and Hall’s Union. It was North who, when writing about the fall of Wolsey in the play, conflated the language and visuals of his own journal with the historical events he was staging. And it is North’s play, now lost, that is the missing link between his journal and the Henry VIII play that Shakespeare and Fletcher co-authored in 1613. (52–3)

2) Michael Blanding, North’s Workbook for 1590s plays, and North’s Outline to Cymbeline

Michael Blanding has been a singular force in recreating the North-family library—and especially books in which Thomas wrote comments in the margins. It is Blanding who has painstakingly searched the archives of myriad libraries in the United States and England for 16th-century books that might have the North family bookplate or had been owned by a North family-member. Then if he finds one, he travels to that library, examines it to see if Thomas has written anything in the margins, and, if so, he takes pictures of the pages.

At Cambridge, he found a copy of North’s own personal copy of his Dial of Princes that North purchased in 1591 and then used as a workbook for plays he revising at that time—like Arden of Faversham and The Taming of the Shrew—or that he was crafting for the first time, like Macbeth. We intend to publish on this soon. But, here, Blanding describes what may be his most spectacular discovery:

By far the most significant book I found, however, was the calf-bound book I was examining at Harvard last October—a 1533 copy of Fabyan’s Chronicles. Written by Robert Fabyan, it is a compendium of English history that predates the more familiar Shakespearean sources of Holinshed and Hall. As I turned the pages, I found it full of Thomas North’s marginalia.

I turned excitedly to the reigns of the various Henrys and the Richards to see if North had noted anything included in Shakespeare’s history plays, but was disappointed to find that he had written little on any of those pages. In fact, he seems to have almost exclusively marked the early chapters of the book on Britain’s Roman-era history. I sent the images to McCarthy telling him that I didn’t think there was much here. He wrote me however to say: “It’s all Cymbeline.”

Now, I’d never read Shakespeare’s Cymbeline (and for good reason, as it’s not one of his better plays). The play is set in Britain during Roman times, as Rome is fighting with Britain over the question of paying tribute. Eventually Rome invades the island and is repulsed by a force led by King Cymbeline’s sons Arviragus and Guiderius. None of it is real history; rather, it’s a conflation of a number of historical events from the chronicles.

But McCarthy began excitedly showing me that nearly every one of North’s notes referred to characters and events from the play. In some cases, the language itself was even the same, as when North and Shakespeare both write that Britain paid to Rome “yearly three thousand pounds.” North even writes the name of a British king Cassibelan as “Cassibulan,” a misspelling found nowhere else but Shakespeare’s First Folio.

There are other common elements as well: Both reference a plot by one character to kill a rival by dressing up in his enemy’s clothes; both refer to a battle fought in Scotland by a wall of turfs more than 100 years later; and North even skips 200 pages to make a note about a deathbed vision by English king Edward the Confessor that also shows up in a dream sequence in Cymbeline.

In this article, I discuss in greater detail this discovery of North’s handwritten outline to Cymbeline in a North-family history book.

3) Many Smaller Smoking Guns

While North’s travel journal and his outline to Cymbeline may be considered a smoking cannon and smoking thermonuclear bomb, respectively, we have also found many smaller smoking guns, which we discuss in our books on the subject (especially Thomas North: The Original Author of the Shakespeare Canon). We will continue to publish these individual, single-play related, smoking guns in this Substack.

Conclusion: Are we really just getting lucky?

Adapted from the last chapter of Thomas North:

And, of course, it is not true that if you compare any two corpuses, you will find they uniquely share parallel lines and passages just by coincidence. Of course they will share common phrases, but they will not share unique lines and word-strings. Indeed, consider the analyses of Shakespeare’s writings made by those attempting to prove the Earl of Oxford or Francis Bacon was the secret author of the canon. They have been scouring the writings of their candidates for more than a century, searching for anything distinctively Shakespearean. But they have yet to produce a single uniquely shared Shakespearean phrase. Not one. All the verbal parallels that they have found are commonplace expressions, typically no more than two or three words in length and appearing in dozens or hundreds of other texts from the era. The same is true for another, more recent candidate, Henry Neville.

But North, it seems, could not write three consecutive pages without crafting something distinctively Shakespearean. He could not even scribble notes in the margins of his books without near-quoting (or, at times, pre-quoting) a Shakespearean play. Indeed, in 2021—after the discovery of all these thousands of verbal parallels; after our book on Thomas North’s travel journal outing North as original author of Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale; after Michael Blanding’s front-page article for The New York Times on our discovery of the George North manuscript; and seven years after our Shakespeare Survey paper revealing North as the original author of Titus Andronicus—Blanding found a copy of Fabyan’s Chronicle that had been annotated by North. And North’s marginal comments not only comprise the outline for all the historical elements used in the plot of Cymbeline; it at times near-quotes the play. For example:

North’s marignal note: Cassibulan became tributary to Rome and paid yearly three thousand pounds. The tribute granted 48 or 50 years before Christ

Cymbeline: Cassibulan /… granted Rome a tribute,

Yearly three thousand pounds (3.1.5, 7–8)While the amount of this annual payment was an historical fact, no one other than North or the playwright has ever described the tribute in this precise language in any known, searchable work in the English language. And what is more, both misspell Cassibellan in the same distinctive way—Cassibulan. This marginal note right here—representing just one of a group of North’s notes outlining the historical elements of Cymbeline—found in a book we never knew existed prior to 2021—constitutes a greater number of unique verbal parallels than have ever been discovered by all the Oxfordians, Baconians, and Nevillians combined. This correspondence is even more compelling than the most significant of the Unabomber-Kaczynski verbal parallels. And this is just the latest example among thousands of North-Shakespeare parallels—and more are coming.

The notion that all this could be coincidental and that we are just repeatedly getting lucky is not a serious one. Thomas North was the author of the source-plays that Shakespeare later adapted for the public theater.

Common Questions

The North discovery certainly prompts many questions. Fortunately, they all have simple answers that may be found in the two Substack FAQs on the subject (Part 1 and Part 2). But here are a few quick answers to the most common ones:

Q. Why wouldn’t North publish his own plays? A. Very few plays from North’s era were ever published because they were not performed publicly—but before small noble audiences. (Click here to read more.)

Q. Why wouldn’t North want money and credit for these plays? A. He did get money and credit for them. But most of his rewards came years earlier when he was writing plays for the Earl of Leicester’s theater troupe or when they were first produced before Queen Elizabeth. (Click here to read more.)

Q. Why wouldn’t others have mentioned this or have complained Shakespeare was getting too much credit for North’s old plays? A. They did mention and complain about it. (Click here to read more.)

Q. Why is North’s identity only being discovered now? A. The discovery required 21st-century digital technologies, massive and searchable literary databases, accessibility to North’s prior texts, etc. (Click here to read more.)

But perhaps most importantly, these questions are truly all moot. For the truly troubling question people have is: “How can anyone have the audacity to claim that Shakespeare would adapt older plays!?” But as shocking as it may seem, that is not even a point in dispute. We know Shakespeare’s source plays existed; no source scholar denies this. We know that there were early versions of Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Henry V, Julius Caesar, The Merchant of Venice, etc. So the question is not whether they existed, but, who wrote them? And we now have proof upon proof that the answer is Thomas North.

Dear Mr. McCarthy,

I recently happened to come across your very interesting book and the extremely persuasive technical analysis you provided regarding Shakespeare authorship issues.

As a result, I've just published a long article on the subject, which substantively focuses on your own outstanding work. Here's the link:

https://www.unz.com/runz/american-pravda-who-wrote-shakespeares-plays/

If you're interested in getting in touch with me, I can be reached at Ron@unz.com.

Love this. I feel like I get to discover one of the most historically important breakthroughs ever before everyone else does. Perhaps there’s something of great value to scholars ignoring your arguments that North is the real author of everything after all.