More Frequently Asked Questions About Thomas North and William Shakespeare (Part 2)

Would Shakespeare really get full authorical credit for close adaptations of North's texts? No one denies this actually occurred with the Roman plays

In the previous post, we answered some of the more common questions about the discovery that Shakespeare adapted old plays written by Thomas North. Here are a few more:

Q. Is it really feasible that Shakespeare would get so much acclaim and full authorial credit for plays that were very close adaptations of North’s writings?

A. No one disputes that this is precisely what happened with the Roman plays. Everyone agrees that Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Coriolanus, and Antony and Cleopatra are extremely close adaptations of North’s corresponding chapters in Plutarch’s Lives, subsuming the storyline, characters, and many of North’s passages verbatim. And yet Shakespeare received all the acclaim and got full authorial credit.

The video above shows a small part of Volumnia’s speech to save Rome. As shown below, the full speech was much longer.

Importantly, the extent of Shakespeare’s dependence on North’s Plutarch is unique — far surpassing his use of any other source (indeed, far exceeding any other writer’s borrowings from any other writer.) All of Shakespeare’s other tragedies and the English histories are extremely original plays that were based on (often very loosely based on) historical events or legends, but they were not, like the Roman plays, straight scene-for-scene, speech-for-speech adaptations, filled with verbatim borrowings from the historical, prose source-texts.

Consider as an example the Prince Hal trilogy—1 Henry IV, 2 Henry IV, and Henry V. All of the memorable scenes and speeches—indeed, even many of the major characters—are the pure invention of the playwright. Pistol, Fluellen, MacMorris, Jamy, Nym, Gower, Hostess Quickly, the Boy, Williams, Poins, Gadshill, Peto, Bardolph, Doll Tearsheet, Justice Shallow, Justice Silence, etc. have no historical counterparts. Even Falstaff, who has more lines in 1 Henry IV than any other character, is entirely a product of the playwright’s imagination—as are all of Falstaff’s scenes, speeches, and dialogue. The only time the playwright does closely follow the historical texts is when he wants to impart expository details accurately—as with the listing of the dead at Agincourt or the recitation of the arcane minutiae of Salic Law, neither of which could he just invent. But all the famous scenes and speeches of the Prince Hal plays—the Gadshill robbery, all the tavern scenes, the fight between Fluellen and Pistol, Henry’s wooing of Katherine, Henry’s talks with the soldiers while in disguise, and the immortal “St. Crispin’s Day” and “Once more into the breach” speeches—are inventions of the dramatist.

This is in stark contrast to the Roman plays, in which few such elements of literary consequence are original. There is no major character or scene that does not derive directly from North’s Plutarch’s Lives. Even most of the major speeches are taken from North’s translation nearly verbatim.1

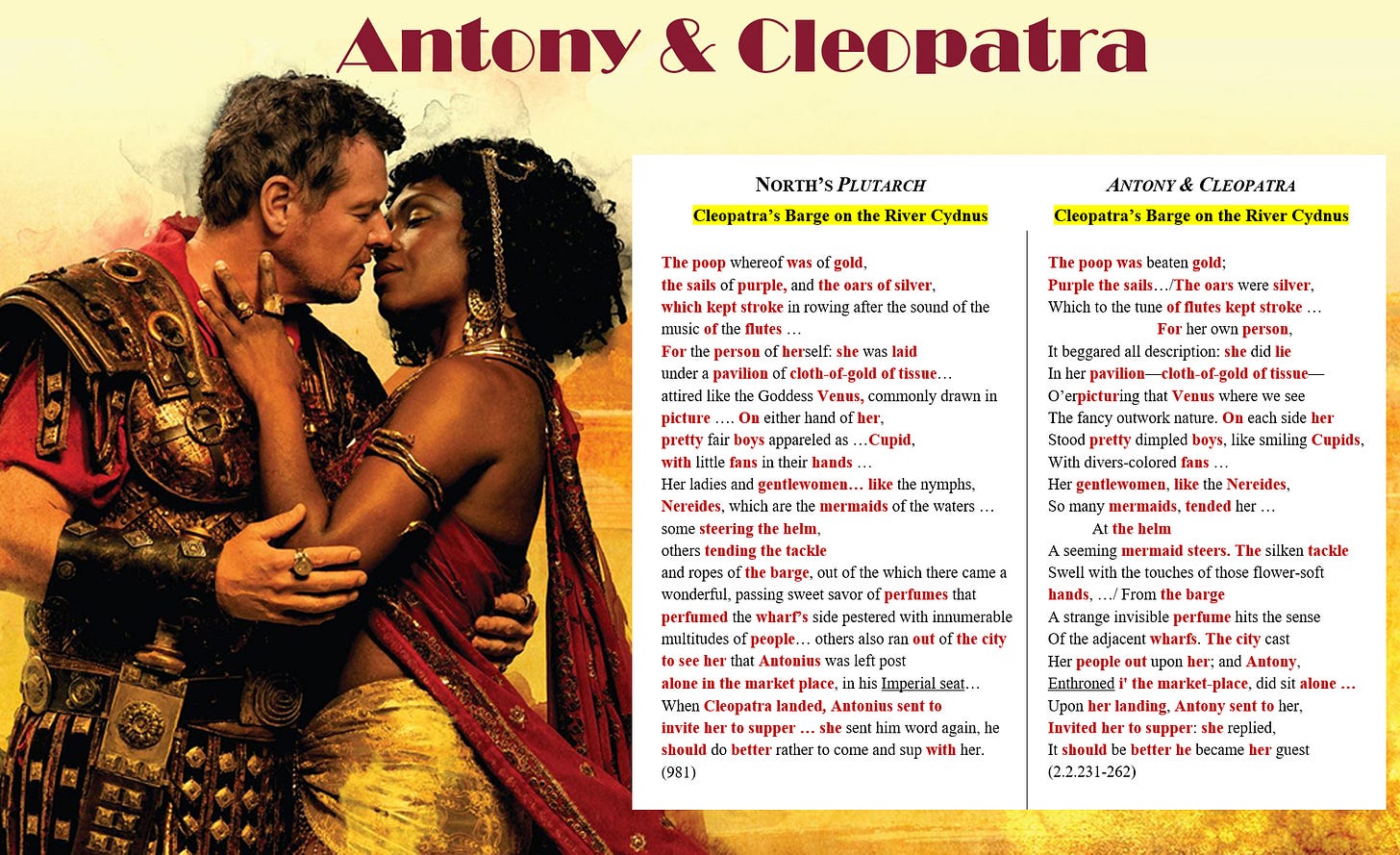

The assassination of Julius Caesar, Caesar’s ghostly visitation to Brutus, Coriolanus’s confrontations with the tribunes, Coriolanus’s meeting with Aufidius, Volumnia’s speech to save Rome, the description of Cleopatra’s voyage up the Cydnus, the suicide-by-asp of Cleopatra, the death of Mark Antony—all of it comes from North.

When scholars first discovered some of these Plutarchan borrowings, they were shocked, and many wholly admitted how strange—even unique—the situation was. As the early twentieth-century professor Walter Alexander Raleigh wrote:

In this as in other cases Holinshed was used by Shakespeare as a kind of mechanical aid to start his imagination on its flight and launch it into its own domain.

With Plutarch the case is far different. The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans was the only supremely great literary work which Shakespeare set himself to fashion into drama. … In Plutarch Shakespeare found some of the most superb passages of the history of the world, great deeds nobly narrated, and great characters worthily drawn. Moreover, his material was already more than half shaped to his hand … Some of the finest pieces of eloquence in the Roman plays are merely Sir Thomas North’s splendid prose strung into blank verse. Shakespeare follows his authority phrase by phrase and word by word … because he knew when to let well alone.2[vii]

To suspend disbelief, one need only turn to Chapter 8 of Thomas North: The Original Author of Shakespeare’s Plays, and peruse the list of 80 Shakespearean passages that have been lifted from North. These correspondences indicate that Antony and Cleopatra, for example, is closer to North’s original chapter on Antony and Cleopatra than, say, the film version of The Silence of the Lambs is to Thomas Harris’s original novel. The same is true with Shakespeare’s Coriolanus. Yet, again, it is only Shakespeare’s name on the title page. (Today, of course, the original author would appear on the title page, along with the clarification that the work is an adaptation. For example, when Ted Tally won an Oscar for The Silence of The Lambs, it was for best adapted screenplay:)

Naturally, I contend that Shakespeare was not borrowing from North’s Plutarch at all, rather he was adapting North’s plays on Coriolanus, Julius Caesar, and Antony and Cleopatra. After all, we know North was writing plays for Leicester’s Men at the time he was working on Plutarch’s Lives, and wouldn’t it have been natural for North to have noticed the dramatic potential of the stories he was writing? The answer to this question becomes more obvious when we discover that the playwright also recycled passages from North’s Dial of Princes in the Roman plays too.

Unfortunately, throughout the 20th century, the natural tendency of professors and students to idealize their intellectual heroes—especially those writers or thinkers who had become the focus of their studies or even careers—led to the downplaying of Shakespeare’s use of North’s Plutarch (along with the minimization of his adaption of old plays). After all, who wants to have devoted their life to an adapter or, gulp, a plagiarist? Soon, academics began to claim that Shakespeare’s borrowings from North were normal for the era—in much the way the townspeople of Hans Christian Andersen’s fable acted like a naked emperor was normal.

Since then, through the use of plagiarism software, we have shown that Shakespeare’s debt to North was far greater than anyone has previously realized, extending far beyond the Roman plays and North’s Plutarch. Shakespeare has actually subsumed thousands of lines and passages from North—with borrowings appearing in essentially every large act of every play and deriving from everything North has has ever written — including his personal papers, his travel-diary, and his marginal notes! Indeed, no one has borrowed more from an earlier writer than Shakespeare has from North, and it is not even close. The second greatest plagiarist in history, whomever you think that may be, has not borrowed one quarter—and likely not one tenth—as many lines and phrases from some particular writer as Shakespeare has from North.3 All attempts to normalize their literary relationship are not really serious—and do little more than expose the stupefying power of preconceived biases and group-dynamics.

To return to the question at hand, we have known for more than a century that Shakespeare would indeed get full credit and even garner worldwide acclaim for what are extremely close adaptations of North’s writings. The only nuance added here is that, in reality, Shakespeare was not plagiarizing North’s translations; he was adapting North’s old plays. And he borrowed more from North than just the Roman plays.

Q. Why didn’t Shakespeare adapt anyone else’s plays and get credit for those?

A. He did. Although this is not well known, other plays such as Locrine, A Yorkshire Tragedy, The London Prodigal, and Sir John Oldcastle were all published with Shakespeare’s name or initials on the title-pages while Shakespeare was living in London. These plays continued to be attributed to Shakespeare for more than a century, and they even appeared in the most official collection of Shakespeare’s plays published in the latter half of the seventeenth century: the Third (1663) and Fourth (1685) Folios. There is no record during this time of anyone questioning their authorship. Today, these plays are considered so inferior or differently styled that they have been removed from the Shakespeare canon. Conventional scholars theorize that publishers conspired to frame Shakespeare for inferior work. In reality, these plays are Shakespeare’s adaptations too. And the only reason they seem so un-Shakespearean is that they were not originally written by North.

Q. Well, aren’t all the source plays lost? And if so, what actually can be said about lost plays?

A. First, some of the source plays are not lost. Chapter 16 in Thomas North: The Original Author of Shakespeare’s Plays, for example, discusses North’s marginal notes related to the extant True Tragedy of Richard III, which, though often garbled, is, in places, a fairly close rendition of North’s original ~1563 version of Richard III. Also, there exists a German translation of North’s source play for Titus Andronicus, and, perhaps, a Dutch translation of what seems to be the source play for Romeo and Juliet. Arden of Faversham is another anonymous play by North that still exists, though it might include some revisions by other playwrights, including Shakespeare.

Also, no play that has been closely adapted is truly lost. Scholars agree that the extant Pericles is not Shakespeare’s original play but has been greatly modified by other writers. But that does not mean Shakespeare’s Pericles has vanished without a trace, or that we can say nothing about the original version, or that Shakespeare’s name should be kept off the title-page. Finally, these source plays have left behind a considerable amount of evidence. This includes fossil passages of North’s in the plays themselves and fossil references to now-missing scenes or lost characters that Shakespeare had eliminated from the extant version.

Q. Why is North’s identity only being discovered now?

A. The discovery required twenty-first-century digital technologies, massive and searchable literary databases, accessibility to North’s prior texts, accessibility to the catalogs of English libraries around the world, plagiarism software, and other modern digital tools—all of which helped uncover important aspects of this story.

But perhaps most importantly, these questions are all moot. For the truly troublesome question that most people have is: “How can anyone have the audacity to claim that Shakespeare would adapt older plays!?” But as shocking as it may seem, that is not even a point in dispute. We know Shakespeare’s source plays existed. No source scholar denies this. We know that there were early versions of Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Henry V, King Lear, Julius Caesar, The Merchant of Venice, etc. So the question is not whether these older plays existed but, merely, who wrote them? And we now have proof upon proof that the answer is Thomas North.

I have been challenged on the accuracy of this statement regarding how few elements of “literary consequence” are original (I had originally written “essentially none.”) Yes, this challenger agrees all characters and all scenes in the Roman plays are from North, but he notes a few of the speeches in Julius Caesar, like Antony’s oration, are mostly original. Also, of course, some beautiful lines have been added to most of the speeches, even those taken from North. But it certainly is a stretch to describe speeches in which one of North’s characters in one of North’s scenes repeats a speech in which over half the lines are North’s as “original.” And the entire point of this paragraph is that these extensive borrowings are clearly unlike Shakespeare’s treatment of other sources, which he does not deny.

Walter Raleigh, Shakespeare (London: Macmillan, 1907), 70–1.

In this video, we provide an analysis of some of the more notorious examples of plagiarism in history, including Kaavya Viswanathan’s, and compare them with Shakespeare’s borrowings from North. Perhaps, the obsessive plagiarist Quentin Rowan may have stolen as many lines from multiple different authors—but still he almost certainly has not recycled as many lines from one particular author as Shakespeare has from North. As Rowan wrote in a confession to his plagiaristic tendencies: “I can only compare it to other kinds of obsession or addictive behavior like gambling or smoking: in that there was no need to do it initially, but once I'd started I couldn't stop and my mind kept finding ways to rationalize the behavior.”

~~Fascinating! Is Thomas North's Plutarch a direct translation of the original work, or does it take significant liberties?~~

Nvm, it seems not based on what you've written!

"He frequently inserted his own language whenever he felt the foreign text needed it,

especially when writing dialogue or speeches."

This is one of the most shocking revelations in my life! I find it hilarious now that people always speak about how Shakespeare lived such an ordinary life, when he was not, in fact, the author of his works. Thomas North was a soldier who lived a full life just like his close contemporaries Lope de Vega and Miguel de Cervantes.