Response to Vox Day & Evolution-Skeptics

Birds & dinosaurs, prehistoric beardogs, the wondrous Chinese racoon dog, proof of speciation, answers to comments on my "Probability Zero" post, and more

My prior post on Vox Day’s Probability Zero: The Mathematical Impossibility of Evolution by Natural Selection has evidently stirred the intelligent-design pot. Not only has Day, himself, responded—but many of his followers have offered a flood of pointed — and often thoughtful — objections. What follows is a sprawling, multi-layered response to both Day and the most substantive critiques raised by his supporters.

In this article, I present a proof of the origin of new species, further confirmation of evolution by natural selection, an explanation of the dinosaurian ancestry of birds, and a look at a remarkable salamander ring species. I also offer a final rebuttal to Vox Day’s central claims. As you proceed, keep an eye out for vicious beardogs, horrifying dogbears, and the shockingly-strange East Asian raccoon dogs — which will all make sense by the end.

Again, evolution is simply the gradual transformation of organisms through changes that accumulate over generations. Put another way, it is the process by which genes become more or less common in a population over time. When a trait spreads because it improves survival or reproduction—while individuals lacking that trait tend to die more often or leave fewer viable offspring—that process is called natural selection.

In general, most evolution-skeptics, when presented with certain evidence, accept certain obvious examples of evolution by natural selection (e.g., the proliferation of lactose tolerance among Northern Europeans or the development of antibiotic resistance). Indeed, many declare it trivially true—and they are right.

Many, like Vox Day, also appear to accept the basics of the evolutionary story for the origins of the roughly eighteen species of finches and the land and marine iguanas on Galápagos. They agree that the finches all derive from a single ancestral finch population that became marooned on the archipelago—and that this population then diversified into 18 varieties on its various islands. A similar story occurs for the land and marine iguanas.

The evolution-skeptics’ inflection point is speciation. They deny that evolutionary processes can lead to speciation. So they stress that the spread of genes for lactose tolerance did not create a new species—and they even marginalize the Galápagos examples by (incorrectly) declaring that all the finches (and iguanas) are the same species. In effect, they accept what we might call microevolution and agree that natural selection can generate wildly different varieties or subspecies. What they reject is that these changes can continue to accumulate, producing greater differentiations and ultimately distinct species. That is, they deny what we might call macroevolution.

Still, a mistaken assumption underlies much of this skepticism. They imagine evolution must proceed through giant, morphological leaps, suddenly and dramatically producing entirely new species. Thus, my response will confirm two points:

1) All evolution is microevolution, and there have been essentially no dramatic jumps.

2) This process of microevolution can result (and has resulted) in new species.

In my evolution post, I provided the example of toy poodles and dachshunds deriving from wolves to show that species are not, as was almost universally believed prior to 1859, entirely immutable. They have not all existed in their present form since they first came to be. Instead, as clear, a single ancestral population can, through a process of selection, differentiate into multiple varieties. Here are a few typical responses:

[free donut aspect ratio writes:]

You use the example of dogs, but I don’t think that does anything to support your position. It’s the same thing, dogs are all still dogs, they can all produce fertile offspring and moreover they can even do so with wolves.

[Avalanche writes:]

Yet NONE of those wolf descendants EVER “evolved” in a cat or a fish or a horse. ALL of the phenotypic modifications you call “evolution” are extensions or blunting of already existing genes! …

No “earthly barrier – a mountain, a sea, a desert” has EVER changed one animal form into an entirely DIFFERENT form!

In fact, we are not as far apart as they suppose. I also agree that evolution is, in almost every case, largely what Avalanche describes as “extensions or blunting of already existing genes” (with additional mutations layered in, which we can address later)—and that we do not observe one biological “form” abruptly giving birth to an entirely different one. Obviously, no fish has ever birthed puppies—and no poodle has ever laid fish eggs.

But the point of the dog example is to establish a very narrow claim: that animals are remarkably plastic and that even small, incremental changes can nonetheless yield dramatic transformations of a “form.” We can see this plainly when we compare the fur, coloration, size, facial structure, and behavior of a Pekingese with that of a wolf.

Now, Avalanche says all these canid types are really the same “form,” and, similarly, “Free donut” asserts that “dogs are still dogs.” But in the same sense, aren’t coyotes also “dogs”? Aren’t they also just the same “form”? And jackals too? And foxes?

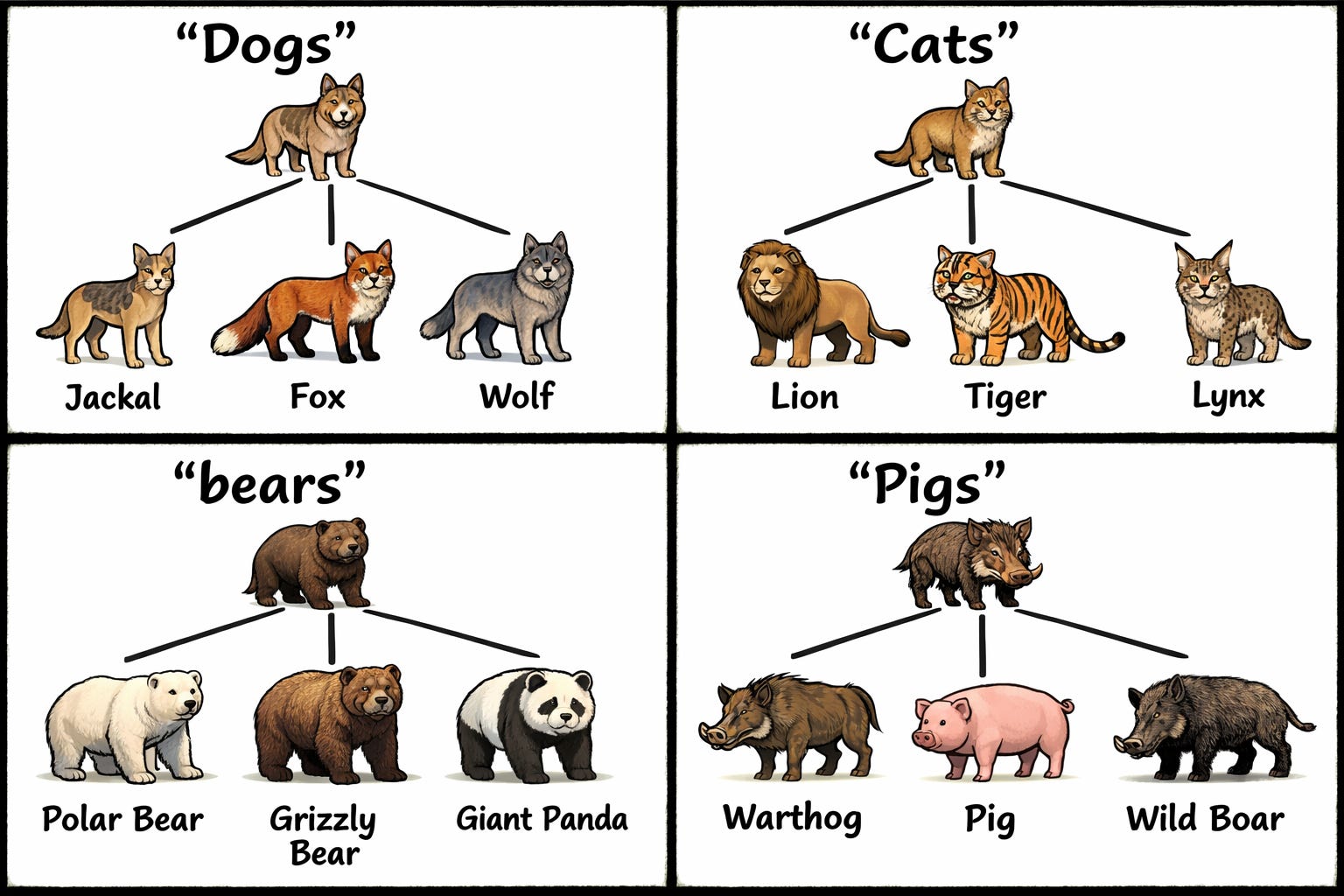

In his response to my island-evolution comic, Vox Day argued that the Galápagos finches—dark ground finches, warbler finches, etc—are all related, just as the land and marine iguanas are. And, again, we can also say these are all the same “form.” Dogs are still dogs; finches are still finches; iguanas are still iguanas. And, of course, we can also make a similar claim with the following illustration of evolutionary trees: bears are still bears; cats are still cats; pigs are still pigs.

So just as we now understand that a wide variety of dog breeds all descend from a wolf ancestor, we should also be able to see how all canids (dogs) derive from an ancestral canid species; how all ursids (bears) derive from an ancestral ursid species; how all felids (cats) derive from an ancestral felid species; and likewise how all suids (pigs) derive from an ancestral suid species. At the very least, we should be able to see how this can occur without invoking some sudden, inexplicable leap. This picture shows precisely what evolutionary theory proposes regarding the origin of species. There are no jumps. It’s micoevolution all the way down.

All the world’s bears don’t show an “entirely DIFFERENT form;” and you just have mostly “extensions … of already existing genes.” We don’t see new organs popping out of nowhere, just the tiniest of modifications acting over many thousands of generations on disjunct populations of already existent forms.

Certainly, if you can understand how a Pekingnese and a Great Dane are related and descend from a common ancestor, it should not seem implausible that a lion and a cougar—or a wolf and a coyote—or a grizzly bear and a polar bear—are likewise related and share common ancestry. If one objects that these, unlike dogs, are not the same species, well, polar bears and grizzly bears can mate and produce fertile offspring, as can lions and tigers. (We will address speciation below.)

Fossil Record

If it is now clear that differentiations of many mammalian species can occur without any fantastic morphological jumps or changes in form, do we have evidence for the fact that this did, in fact, happen? Yes. As expected, fossils from tens of millions of years ago contain no examples of panda bears, grizzlies, lions, wolves, or any of the modern mammals that dominate today’s ecosystems. Instead, we find more primitive ancestral forms—early bear-like carnivorans, cat-like predators, and dog-like hunters that share only the broad structural traits of their modern descendants. Over long stretches of time, those generalized lineages split, adapted to new environments, and accumulated refinements, eventually giving rise to the distinct bears, felines, and canines we recognize today.

The absence of modern species deep in the past is exactly what we should expect if today’s mammals are the end products of long, branching histories rather than creatures that appeared fully formed.

Moreover, both genetic evidence and the fossil record indicate that the closest living relatives of the dog family are bears and raccoons. The fossil record also documents the existence of “beardogs” (Amphicyonidae)—not direct ancestors of either group, but close relatives to both canids and ursids. The name Amphicyon literally means “ambiguous dog.” Distinct from these were the so-called “dog-bears” (Hemicyon, meaning “half-dog”), which formed an ancient branch within the bear family (Ursidae).

Avalanche objects that we do not see dogs turn into cats, but dogs and cats are not especially close relatives. Dogs are far more closely related to bears and raccoons—and, strikingly, we have seen canids evolve into animals that look remarkably raccoon-like. Consider the following two pictures: these are actually not raccoons, but the common raccoon dog, a canid native to East Asia.

The common raccoon dog is the only canid that hibernates and can climb trees, much like a raccoon. This shows that even if we just accept “the blunting and extensions of already existent genes” (to use Avalanche’s phrase), we can still find remarkable behavioral and phenotypic transformations in which you get a dog turning into something very raccoon-like.

Kevin Schumacher writes: This elaborates on Micro-evolution which are built upon three micro-evolution premises(upon which Creation, Intelligent Design proponents agree as you correctly noted), but it does not address Macro-evolution and which commits the fallacy of proving too much, e.g., we have transitional fossils along the evolutionary path from Mesohippus to Equus (the modern horse), therefore horses can eventually become birds.

Let me respond directly here: Keven, if you accept that Equus evolved from Mesohippus, then you already accept Darwinian evolution in its essentials. You accept, as the fossil record and all other evidence demand, that the mammals living today were not always on Earth but descended from more primitive mammalian ancestors.

You also write of “horses turning to birds,” but, according to evolution, that would be impossible and require a major, sideways jump. Birds did not evolve from horses; they actually evolved from dinosaurs, which, as we see in the next comment, “free donut aspect ratio” thinks is even more ridiculous than horses turning into birds:

“free donut aspect ratio”:

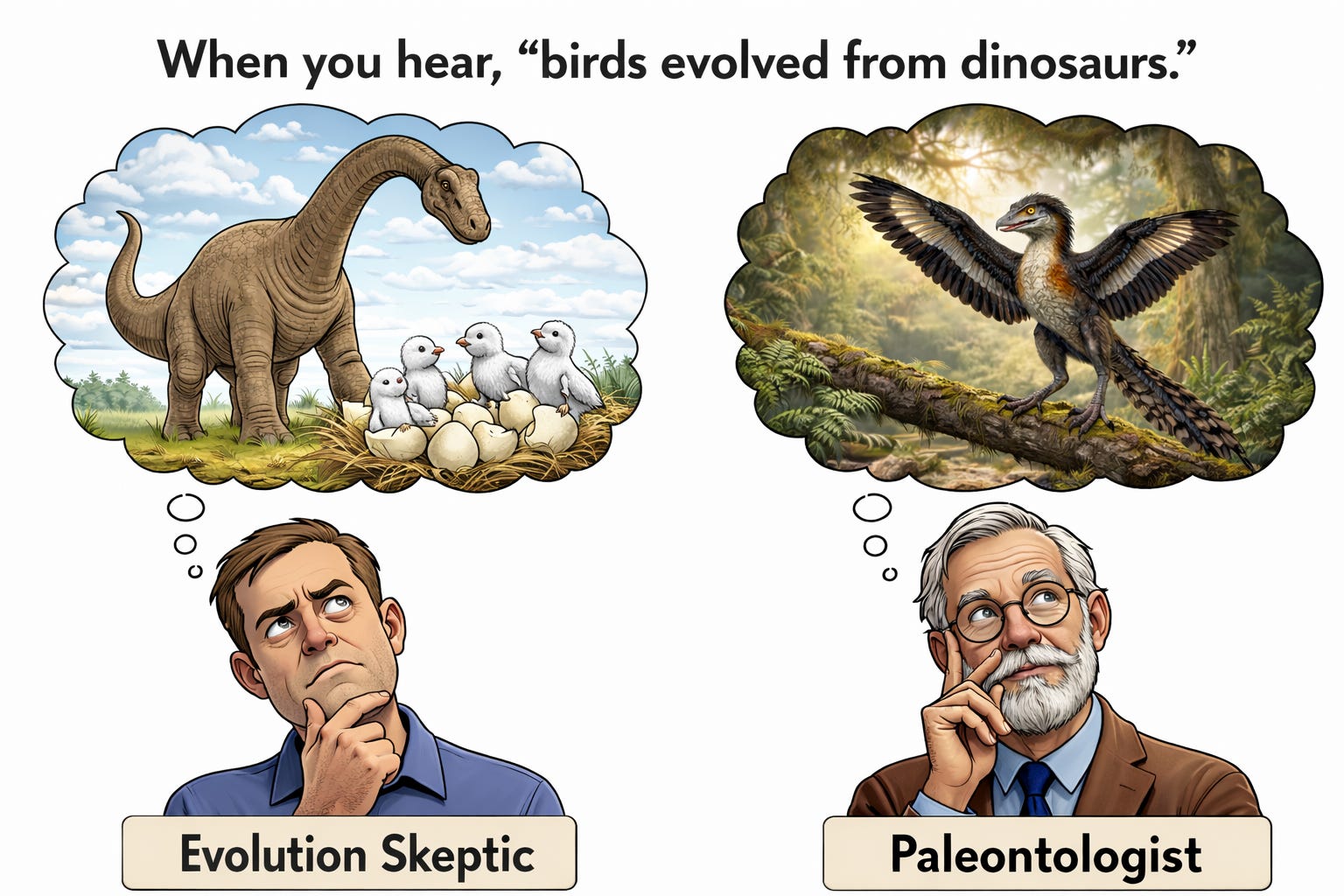

but evolutionary theory does believe that dinosaurs eventually became birds, so that doesn’t seem like a strawman. That is if anything more far-fetched since horses and birds are at least both warm-blooded.

Of course, when evolutionary theorists note that birds evolved from dinosaurs, they don’t mean doves suddenly hatched from the eggs of a sauropod. Instead, they contend that birds evolved from three-toed, tree-climbing theropods, whose scale-like skin filaments had evolved after many thousands of generations into longer and longer feathers. In other words, they contend birds evolved from Archaeopteryx-like theropods—not from a sauropod or a Stegasaurus.

In the cartoon above, the paleontologist is picturing an Archaeopteryx, which was a close relative to the ancestor of all modern birds that combines bird-like and dinosaur-like features. On the bird side, it possessed fully modern flight feathers, a furcula (wishbone), and a lightweight body. On the dinosaur side, it still had teeth, a long bony tail composed of many vertebrae, three separate clawed fingers on each wing, a theropod-style pelvis and shoulder girdle, and feet that are essentially those of small predatory dinosaurs. It can literally be called a dino/bird.

If you compare the claws of a cassowary …

with those of a theropod dinosaur, you will notice many similarities:

Theropod (left)

Toes are thicker and more cylindrical

Claws are slightly deeper and more laterally compressed

Foot looks optimized for gripping prey and weight-bearing

Rear toe (hallux) would be small, elevated, or absent in most theropods

Cassowary (right)

Toes are a bit longer and more flexible

Claws slightly narrower and more curved

Skin texture often shows finer scaling

Has a fully reversed hallux (rear toe) for grasping

Again, evolution consists of extremely minor changes occurring in populations over many generations. It’s microevolution all the way down.

Speciation

As noted, the major concern of evolution-skeptics is speciation.

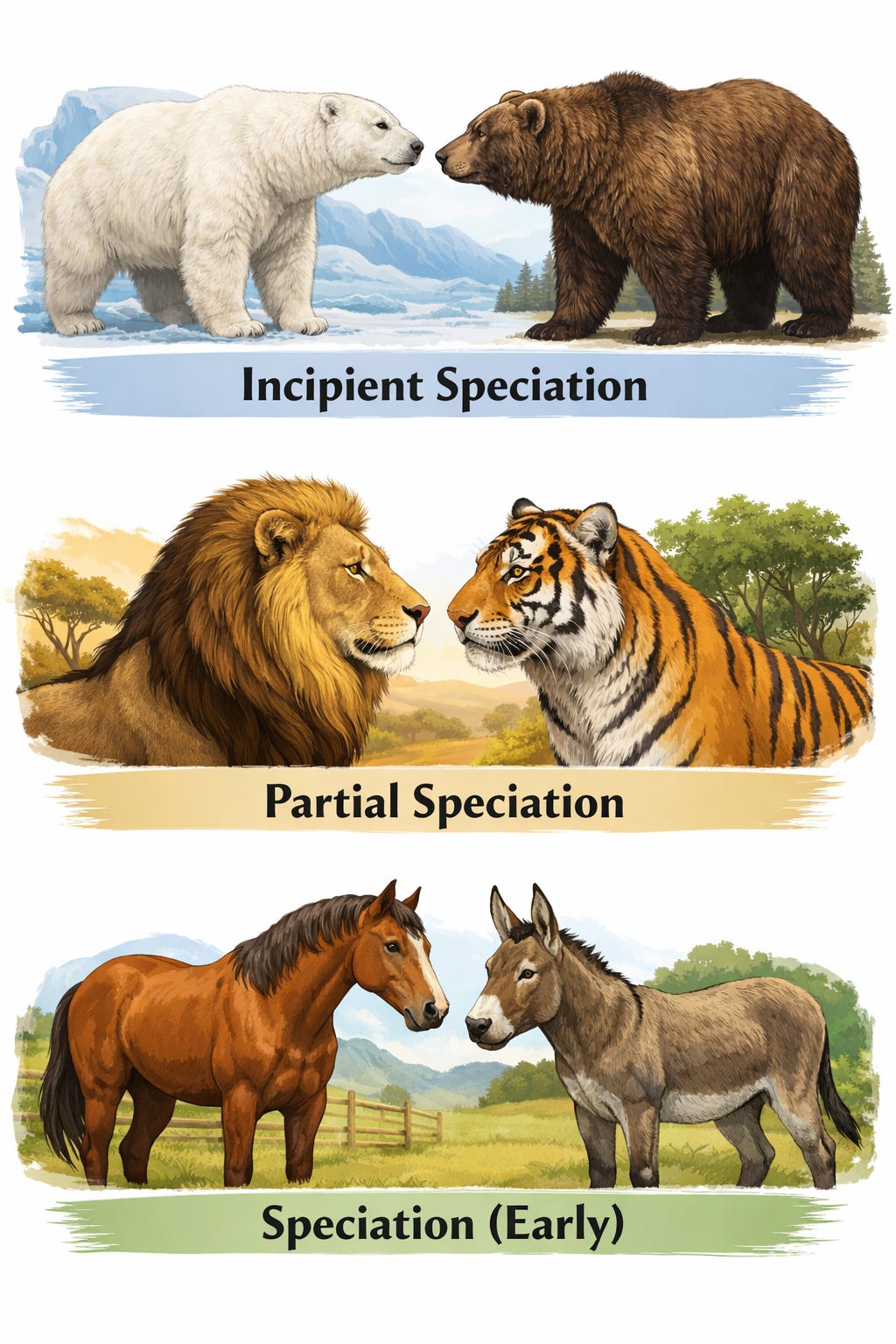

Importantly, speciation is not a single dramatic event but a gradual process that unfolds as populations within a species become divided and increasingly isolated. As these separated groups accumulate differences, they grow progressively less reproductively compatible, and their hybrids become steadily less viable over time.

Single Species: In close-knit populations, individuals freely interbreed, and genes flow throughout the group. Thus, any new mutation—good, bad, or neutral—can spread across the entire population because mating constantly mixes genetic material.

Divided Populations of the Same Species: The first step toward speciation occurs when gene flow is reduced or interrupted—as can happen when a population ends up stranded on a new island or some geographical barrier (mountain range, river, desert, etc.) forms within the range of a species, separating them into two or more populations. Once this separation occurs, even imperfectly, the populations begin to evolve independently, responding at times to very different selective pressures. Also, importantly, they stop sharing random changes that occur in the genomes, which are known as mutations. This moment—when gene flow drops—is the true starting point of speciation.

Incipient Speciation: Early on, the two populations are still genetically very similar. They can usually still interbreed if they meet, and their offspring are viable and often fertile. This stage is called incipient speciation. Reproductive isolation exists, but it is weak and often indirect. Polar bears and grizzly bears illustrate this stage. They diverged relatively recently, occupy different ecological niches, and rarely meet in the wild. But when they do, they can produce viable hybrids. That compatibility tells us the genetic separation is still shallow.

Partial Speciation with Incomplete Isolation: With continued separation, differences accumulate across the genome. Each population acquires new mutations on every chromosome, generation after generation, none of which are shared. Genetic drift and selection gradually alter gene regulation, protein interactions, and development. At this partial speciation stage, hybrids may still form but often show reduced fitness or fertility. Selection then favors avoiding hybridization altogether, strengthening reproductive barriers. Lions and tigers fall near this stage: hybridization is possible, but fertility problems—especially in males—reflect growing genetic incompatibilities.

Full Speciation: Over longer periods, chromosomal changes such as inversions, fusions, or translocations can prevent proper chromosome pairing during meiosis. This leads to sterility or inviability even when mating occurs, effectively halting gene flow. The classic example is the horse and donkey: they can produce a mule, but the mule is almost always sterile. At this point, speciation is complete—reproduction may occur, but it no longer has evolutionary consequences.

The unifying principle is time. Once populations stop exchanging genes, each lineage accumulates its own genetic history. Over thousands to millions of years, these differences inevitably build until successful reproduction is no longer possible.

Again, none of this should be surprising, let alone seem impossible. Steady differentiations in the DNA of divided populations ensure that, over time, they become less and less compatible.

Proof of Speciation

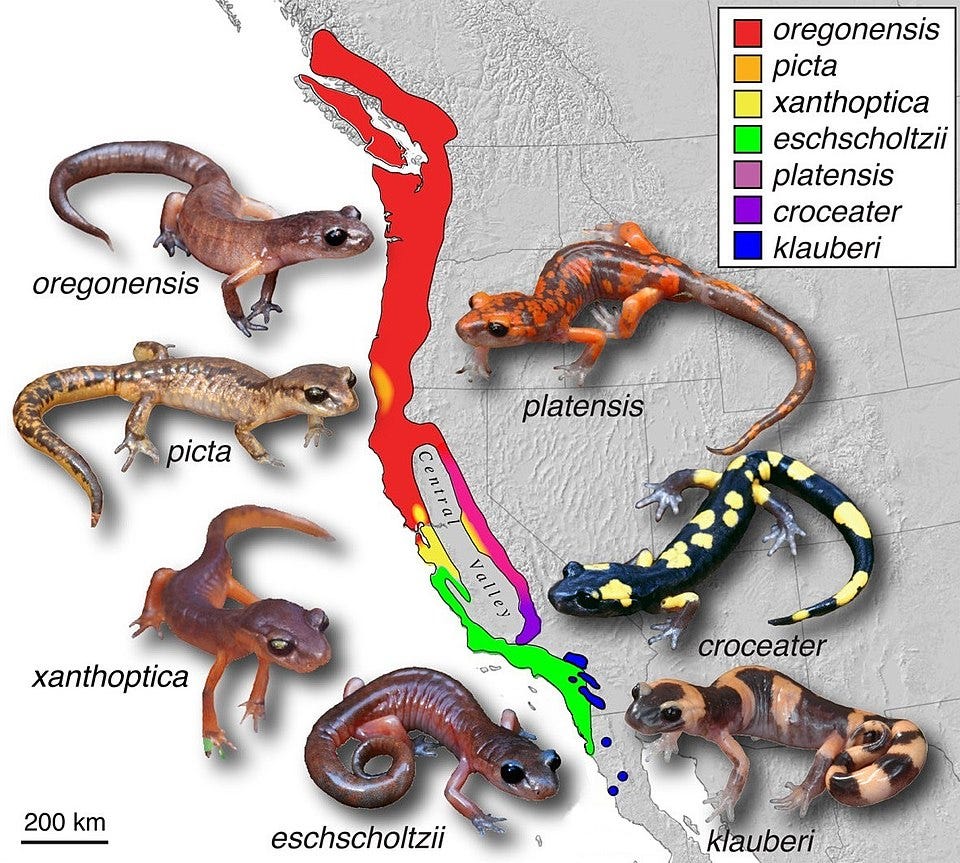

A spectacular example of an organic bond moving through space that consistently leads to greater and greater reproductive incompatibility should help clarify this process of speciation. Those who hike or tour along western North America, if looking for it, will notice certain species giving way to similar species in nearby regions—just as Charles Darwin had observed in South America. The Giant Sequoias of Western Sierra Nevada and the Coast Redwoods of California provide one example. But the biologist David B. Wake of U.C. Berkeley has discovered a far more interesting case involving the small Ensatina salamander that inhabits Southern California.

Basically, an ancestral population of this salamander began at the northern most point of the San Joaquin valley and then continued to spread along two different southward paths, one along the western edge of the valley, the other along the eastern edge. As the center of the valley was too hot and dry for the amphibians, the eastern and western populations never intermingled and started evolving to different selective pressures. Along the western side, the salamanders become more reddish, matching the color of a local, poisonous newt that many predators know to avoid. Along the eastern side, the salamanders developed dark splotches, some with yellow spots, both of which helped provide camouflage. These two strands of salamanders then met up again at the southern part of the valley.

And here’s the thing: While all the pairs of neighboring populations continue to mate as you encircle the valley, the genetic differences eventually become so great that the two salamander populations at the southern edge no longer successfully interbreed. They have become reproductively isolated and meet the criteria for designation as separate species according to the biological species concept.1

The history of the salamanders may seem unique, but, ignoring the strangeness of the distributional ring, it is a relatively standard evolutionary tale. The reproductive separation of the east and west valley salamanders have resulted, through natural selection, in the diversification into two species. The only reason this example seems so particularly compelling is that so many of the intermediary forms have done us the favor of surviving. The groups were also nice enough to bring the two most divergent end-products of evolution back together again in the same place for a direct comparison.

Some people who deny evolution like to point to gaps in the fossil record, claiming no evidence suggests one species can evolve into another. When we find fossils that are either ancestral or directly intermediate between two forms—and, today, our museums brim with countless such fossils—the common retort is that gaps now exist between this intermediary and the existing species. Since we will never have fossils of every successive generation of a particular organism for tens of millions of years, one can always claim gaps. With the salamanders, however, we have no significant gaps. Each of the salamander subspecies can interbreed successfully with its closest neighbor -- until we get to the two divergent groups at the southern end of the valley. The salamanders display small genetic changes, occurring through space, shaped by natural selection, resulting eventually in the development of two distinct species. While the evidence for evolution in the fossil record is overwhelming, it is biogeography that provides proof positive of the mutability of species.

Response to Vox Day

“Ahh,” says the evolution-skeptic, “I don’t care about fossils or biogeography or stories about salamanders or moths. Vox Day has proved mathematically that it can’t happen, so I don’t even have to think about any of this.”

First, Vox Day’s central argument in Probability Zero concerns neutral mutation fixation rates, which says nothing about natural selection and is largely orthogonal to most of what we have been discussing. Even if Motoo Kimura’s neutral theory—and the equations Vox Day disputes—were entirely mistaken, that would not overturn Darwinian evolution, nor would it undermine any of the empirical facts or conclusions considered so far. Vox Day himself effectively concedes as much in his response:

And in the interest of perfect clarity, note this: Dennis McCarthy’s critique of Probability Zero is not, in any way, a defense of evolution by natural selection. Nor can it be cited as a defense of speciation or Darwinism at all, because neutral theory has as about as much to do with Darwin as the Book of Genesis

Actually, my full post response (like this one) did indeed defend evolution by natural selection. And the only reason I veered from the subject of Darwinism at all was to address Vox Day’s main mathematical arguments—and it is Day’s main arguments that are not relevant to Darwinism or evolution by natural selection. And this is true despite what Day frequently implies, what his readers persistently infer, and what the subtitle of Probability Zero plainly states.

Secondly, as I showed, his two main analyses were both flawed. He contended that it was essentially impossible, given the circumstances of mutation rates, population size, fixation-probability, etc., for the human lineage to have acquired 20 million fixed mutations in the nine million years since humans and chimpanzees last shared an ancestor.

In my response, I used Vox Day’s numbers, noting that in a population of 10,000 humans, we would expect, on average, 50,000 new mutations per year—which is roughly 1,000,000 new mutations per generation. And over the course of 9 million years (or 450,000 generations), we would expect:

50,000 x 9 million = 450 billion new mutations altogether.

So out of 450 billion mutations, how many mutations may we expect to achieve fixation? Well, as Vox Day noted, each mutation has a probability of 1/20,000 in becoming fixed.

450 billion x 1/20,000 = 22.5 million fixed mutations.

And that is a pretty close approximation to the 20 million fixed mutations that have been observed. Change the assumptions, and the estimate moves. But under Vox’s own assumptions, the result is the opposite of “probability zero”: it’s basically what you’d predict.

In Vox Day’s response, after a few paragraphs of feints, he writes that: “it’s technically correct, but misses the point.” The point he contends I missed is that I didn’t take into account how long a mutation takes to become fixed. Quoting:

Because if McCarthy had understood that he was utilizing Kimura’s fixation model in his critique, then he would known to have taken into account that the expected time to fixation of a neutral mutation is approximately 4Nₑ generations, which is around 40,000 generations for an effective population size of 10,000.

He is right that I did ignore it, but I did so because it wasn’t part of his calculations. And introducing this rate doesn’t change the results much—and does so only to my benefit. So in the first generation after the chimpanzee/human split, there were 1,000,000 new mutations—1/20,000 of which may be expected to reach fixation—or 50 fixed mutations per generation. But we should not expect these 50 mutations to fix immediately, but after 40,000 generations. 50 more mutations from the 2nd generation should fix around the 40,001st generation. And so on.

Since hominids have had 450,000 generations, all mutations would have had time to fix except for those mutations occurring in the last 40,000 generations. What is more, the human race has been widely dispersed for tens of thousands of years, with some populations living in constant isolation, necessarily preventing them from sharing mutations with the rest of the world. So let’s subtract out the last 50,000 generations, which leaves us with 400,000 generations.

400,000 generations x 50 fixed mutations per generation = 20 million fixed mutations.

We can also calucate this another way: 400,000 generations x 1,000,000 new mutations per generation = 400 billion new mutations altogether. Each new mutation has a probability of 1/20,000 in becoming fixed, so:

400 billion mutations x 1/20,000 = 20 million fixed mutations.

And that equals the 20 million fixed mutations that have been observed. Change the assumptions, and the estimate moves. But under Vox’s own assumptions, the result is the opposite of “probability zero”: it’s what you’d predict. [New edit 2/3/2026: These are using Day’s numbers, and they are close enough. Double-checking on Google AI, latest research suggests 17.5 million single-nucleotide differences along the human line, and the split was 6-7 million years or 300,000 to 350,00 generations ago. This again works out to about 50 fixed mutations per generation.]

In his other argument, Vox Day applies the mutational fixation rate of bacteria to humans, noting it doesn’t work. There aren’t enough generations. I responded that this is expected as bacteria and humans have very different mutation rates per individual and so very different fixed-mutation rates per generation. Day responds:

McCarthy is correct that humans have a higher per-genome mutation rate than E. coli—roughly 60-100 de novo mutations per human generation versus roughly one mutation per 1000-2400 bacterial divisions. But this observation is irrelevant. Once again, he’s confusing mutation with fixation.

I didn’t cite the E. coli study for its mutation rate but for its fixation rate: 25 mutations fixed in 40,000 generations, yielding an average of 1,600 generations per fixed mutation. These 25 mutations were not fixed sequentially—they fixed in parallel. So the 1,600-generation rate already takes parallel fixation into account.

I stressed the extraordinarily low number of mutations-per-generation of bacteria to explain the extraordinarily low number of mutational-fixations-per-generation of bacteria. When there are fewer mutations available to fix, then you end up with fewer fixed mutations. Bacteria in the experiment averaged one fixed mutation for every 1600 generations. Our hominid ancestors averaged 50 fixed mutations per generation. If you apply bacteria mutation-fixation rates to hominids, you get incorrect results. If you apply hominid mutation-fixation rates to hominids, you get the correct results. 50 fixed mutations per generation x 400,000 generations = 20 million fixed mutations.

Vox Day continues: “No one has ever observed any human or even mammalian fixation faster than 1,600 generations.

Vox Day here appears to be referring to the expected time it takes a single neutral mutation to reach fixation, which as shown above is 40,000 generations for our ancestral line after the chimp-split. But that is not the same as the amount of expected number of fixed mutations per generation, which as we showed above is 50 fixed mutations per generation. For the past 9 million years, all mutations for 400,000 generations have had time to fix, leading to 20 million fixed mutations.

Also, Day starts discussing beneficial mutations, and in regional mammalian populations, beneficial mutations can, under severe selective pressures, sweep to fixation across the entire population in only tens or hundreds of generations. Numerous lab and field studies confirm this (e.g., Steiner, C. C., Weber, J. N., & Hoekstra, H. E. (2007). Adaptive variation in beach mice produced by two interacting pigmentation genes. PLoS Biology 5(9): e219.)

Common sense also confirms this. If a particular environment is killing off every individual that lacks a given trait, then within a short time, every surviving member of that population will possess it.

Vox Day continues: Even if we very generously extrapolate from the existing CCR5-delta32 mutation that underwent the most intense selection pressure ever observed, the fastest we could get, in theory, is 2,278 generations, and even that fixation will never happen because the absence of the Black Death means there is no longer any selection pressure or fitness advantage being granted by that specific mutation.

Vox Day defines fixed as occurring in 100% of the human race everywhere around the globe and now refers to beneficial mutations appearing in humans within the last thousand years. But evolutionary theory predicts that no mutation, whether neutral or beneficial, that has arisen in the last 50,000 years or so can reach and spread throughout all populations on the planet. The reason is that over that time—and especially over the last 10,000 years—human populations have become fragmented and geographically isolated in places such as New Guinea, Australia, Tasmania, the Andaman Islands, the Pacific islands, and the Americas.

Most people of these regions have had effectively zero genetic contact with the rest of the world until very recently, if at all. Under such conditions, it has been impossible for any single mutation—whether neutral or beneficial—to reach fixation across the entire human species. The genes that helped some Europeans survive the Black Death in the 1300s, for example, could never have also raced across the Americas (neither group even knew each other existed at this time), let alone reach the Hewa people of New Guinea, who would not see a white person until 1975.

Instead, the roughly 20 million fixed genetic differences between humans and chimpanzees accumulated during the millions of years when ancestral hominid populations were relatively small, geographically concentrated, and tightly interconnected by gene flow.

Given this, the rapid rise of lactase persistence in Northern Europe between roughly 8,000 and 3,000 years ago is especially revealing. Although Northern Europeans already numbered in the millions, they still constituted a far more cohesive, interbreeding population than humanity as a whole. This makes them a much better proxy for the small, interconnected ancestral populations in which essentially all human fixations occurred. The near-fixation of lactase persistence across this region within a few thousand years demonstrates just how quickly a strongly beneficial mutation can spread through such a population.

Biologists quarrel over whether these salamanders represent a pure example of what is known in biogeography as a ring species—that is, a species that continues to exhibit slight changes as you travel around the circle until you finally come to a point in the loop where the populations have effectively become two different species. Purists point out that, by definition, a ring species refers to a species whose gene flow has never been interrupted, and it seems like some of the salamander subspecies had, at some point, experienced separation from their neighbors, accelerating genetic differentiation. Regardless, it still remains a clear example of evolution by natural selection and speciation.

That's a well-informed argument, Dennis. Nicely done. As before, I'll link to this today and give everyone a day to comment upon this here before I provide my response.

And once more, I am extremely grateful to you for presenting this argument, as your beach mouse study has opened a door that should prove fascinating for everyone on both sides of this discussion.

First few paragraphs already show Dennis still hasn't understood the real scientific question. He opens with yet more strawmen fallacies, confusing evolution with neodarwinism, skeptics of neodarwinism with skeptics of evolution, species with subspecies, and more.

Last week we saw Dennis didn't know that the original lactose tolerance and peppered moth stories fell apart years ago. He didn't know most of his examples weren't even about new species. And of course he misrepresented Vox's argument. It was a complete and highly embarrassing disaster.

Neodarwinists and creationists are equally naive and unscientific. Neodarwinism has become a cult defending a naked emperor, and Dennis cannot escape this cult because a large part of his own identity, life and work are tied up with this cult. It's sad, but we cannot change it.

Better spend some more time on Shakespeare.