Thomas North's Sister Commited the Murder of the 16th-Century (& She's the Basis for Lady Macbeth)

The majority--yes, the majority--of the most famous scenes in the Shakespeare canon come from North's life or writings

This would become the crime of the century—the most notorious murder of a private citizen in the Tudor era

On a snowy Saturday night on St. Valentine’s Day, 1551, Thomas Arden sat at a parlor table across from Thomas Mosby, a backgammon board between them. Alice, Arden’s wife, prepared their supper and cleaned the room, but she still seemed agitated. She had at first tried to stop Mosby from entering the house. She argued that Mosby liked to hang with a rough crowd, and, worse, neighbors were gossiping that she and Mosby were having an affair. She furiously demanded that he leave their home and never return. Mosby agreed, but Arden pleaded for calm. “Alice, bid him welcome,” Arden said. “He and I are friends.”

It was not a surprise that Faversham locals were whispering. Alice had actually known the dark and handsome Mosby before she had met her husband. Mosby was a household servant—a live-in tailor—for Alice’s wealthy step-father, and the 14-pound pressing iron that was tied to his waistband indicated he still worked for her family in that occupation. When Alice was a teenager, she and Mosby resided at the same estates, and Alice would still see Mosby whenever she visited her family on holidays. Also, Mosby would occasionally travel to the Arden home in Faversham to visit his sister, Susan, another long-time servant of Alice’s family. Susan was also in the house, doing chores, as Arden and Mosby played backgammon.

“What shall we play for?” asked Arden.

“Three games for a French crown, sir, and please you,” Mosby responded.

“Content.” Arden started rolling.

Despite Arden’s welcoming of Mosby, he was a jealous and controlling husband. He too had at times suspected that Mosby and his wife were having an affair or at least that they were romantically involved at some point in the past. But he often ignored or suppressed those feelings—perhaps because he didn’t want to believe it or perhaps because he wanted to avoid any difficulties with Alice’s powerful family. Also, Alice had repeatedly convinced Arden that she never had feelings for her family servant, and now it even seemed as if she hated him. Didn’t she just insult Mosby and demand that he leave? All this helped to put Arden’s mind at ease.

As the two men played, Alice quietly unlocked the closet door behind her husband, and a large man—an ex-soldier and criminal known only by the name Black Will—stepped from its shadows. He held a thick rope-like towel taut between his hands. Mosby could see the shadowy hulk behind Arden but remained expressionless, still feigning interest in the backgammon game. He then rolled the dice.

“Ah, Master Arden, now I can take you,” Mosby said, not taking his gaze from Arden. The comment was an obvious cue to Black Will, who lunged from the darkness and wrapped the rope around Arden’s neck. He violently yanked him backward, pulling Arden onto the floor on top of himself. Arden struggled but was helpless: “Mosby … Alice,” Arden said, terrified and pleading. “What will you do?” Black Will, still strangling his victim, said to him, “Nothing but take you up, sir, nothing else.”

Mosby took the flat iron from his waistband and smashed Arden’s head, causing his limp body to slide off Black Will. The men thought they had killed him, but Alice, holding a large kitchen knife, heard her husband make a guttural moan: “Groans thou?” Alice asked, straddling Arden. “Nay, then … take this for hindering Mosby’s love and mine.” She stabbed him again and again as blood pumped and splashed around the room.

This would become the crime of the century—the most notorious murder of a private citizen in the Tudor era. The slaying became so infamous that Holinshed’s Chronicles, the somber and definitive Elizabethan source of English history, devoted five full pages to the case, discussing its events in detail. This is far more than the tome allocated to most matters of state or any other domestic crime, which typically got a sentence or two. John Stowe, the historian writing for Holinshed, explained this focus by referring to the “horribleness” of the act in which Arden was “most cruelly murdered and slain by the procurement of his own wife.”1 Richard Helgerson also contends that “the Arden story’s continuing hold on the imagination of successive generations, both in and out of Faversham” was due in part to the fascination with the villainess.2 Alice’s betrayal would eventually become the subject of a puppet show, a broadside ballad, a novel, an opera, a ballet, a nursery rhyme, and even an anonymous play—Arden of Faversham—first published in 1592. The dialogue and description of the murder above is largely taken from that play. Arden’s large Tudor house still stands in Faversham and has become a tourist attraction.

This was also one of the earliest events that fully captured Thomas North’s attention, disrupting the serenity of his childhood and almost certainly rattling his very sense of the world. The murder took place a few months before he turned 16, but the reason it affected the young Thomas so viscerally is not the extraordinary public interest generated by the crime. In fact, most of this attention, including Holinshed’s historical account, would not come till decades afterward. Nor did North find it so affecting simply because of the peculiarly “Shakespearean” elements of the tale, centered, as it was, on jealousy, treachery, lust, murder, and a fitting recompense for those who succumb to unbridled passions and darker impulses.

No, the reason we know that this crime comprised the most staggering moment of his young life is that Alice Arden—the best-known murderess of the sixteenth century—was Thomas North’s half-sister, Mosby was a North family servant, and the estates where they had met and both resided were North’s family manors of Kirtling Hall and the Charterhouse. Young Thomas personally knew everyone involved in the crime.

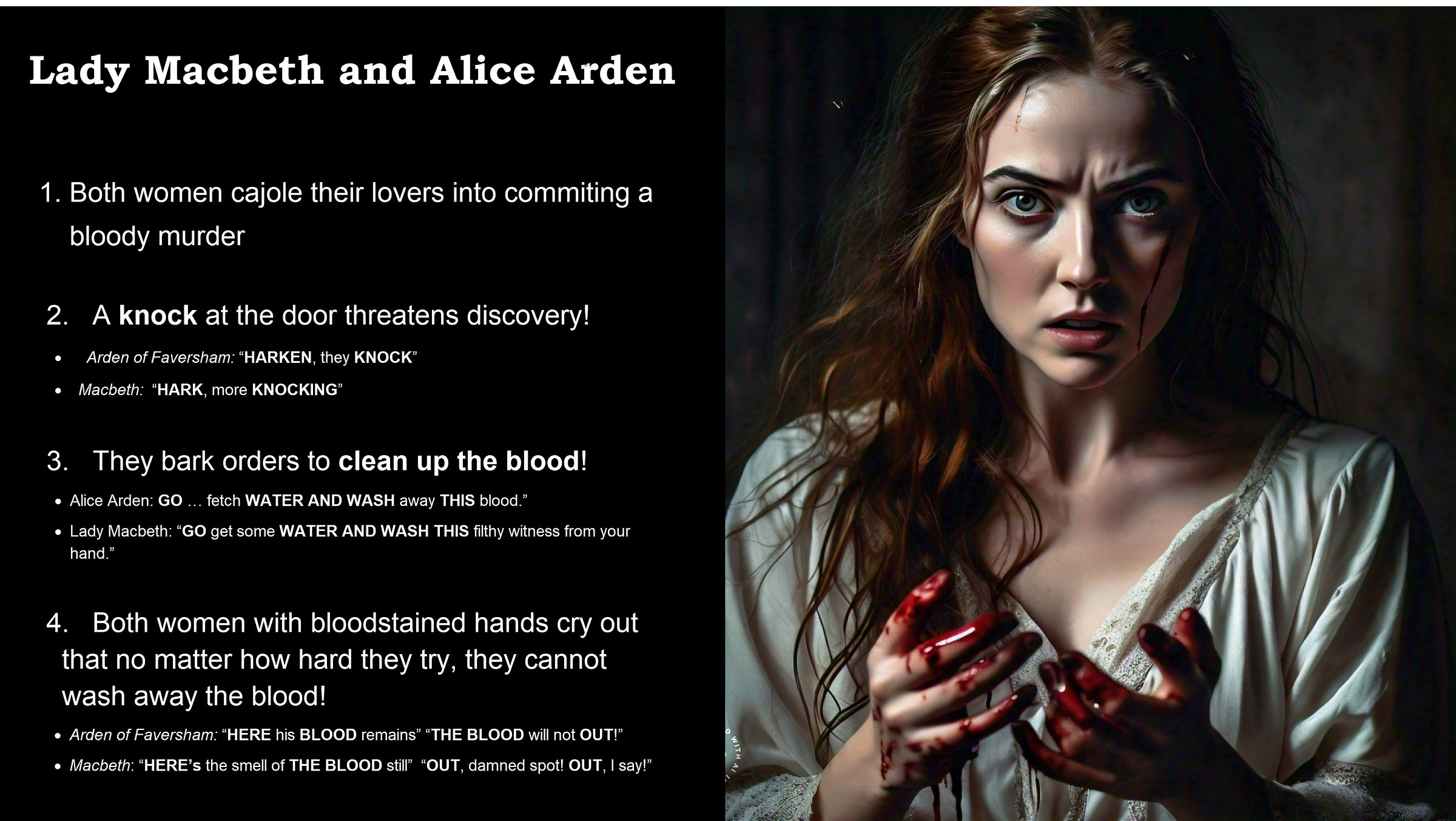

Lady Macbeth and Alice Arden

Arden of Faversham, the tragedy written about the murder, holds a special fascination for Shakespeare scholars because, along with Edward III, it is one of only two extra-canonical dramas that many have argued should be credited to Shakespeare on the grounds of quality and style alone. The first known claim of Shakespeare’s authorship dates back to 1770 when the Faversham historian Edward Jacob commented on its ingenious and distinctive features in a preface to a reprint of the tragedy.3 Since then, numerous scholars have discussed its “Shakespearean” qualities, including the skillful unraveling of plot, the depth of characterization, and many passages, phrases, and scenes that appear to be echoed in the Shakespeare canon. As the renowned literatus Algernon Swinburne remarked, “Either this play is the young Shakespeare’s first tragic masterpiece, or there was a writer unknown to us then alive and at work for the stage who excelled him as a tragic dramatist. …” He then referred to the play as “the possible work of no man’s youthful hand but Shakespeare’s.”4 Shakespeare biographer Sidney Lee agreed: while “there is no external evidence in favour of Shakespeare’s authorship,” its “dramatic energy is of a quality not to be discerned in the work of any contemporary whose writings are extant.”5 And Marion Bodwell Smith recorded numerous images and passages found in Arden that recall similar elements in the early plays of Shakespeare.6

Extending this argument, Bryan Aubrey focused on the Shakespearean qualities of Alice Arden herself, placing her on the same pedestal as Shakespeare’s most significant of female roles and, especially, Lady Macbeth.7 Similarly, Hardin Craig refers to the “moving tragedy” as “a masterpiece of psychological interpretation, which foreshadows Macbeth.”8 This comparison even dates back to the nineteenth century, when two German editors, Karl Warnke and Ludwig Proescholdt, were among the first to depict Alice as “a predecessor of Lady Macbeth.”9

In recent years, MacDonald P. Jackson and Arthur F. Kinney have independently used literary search engines to help aid in attribution, connecting many of the lines and passages in Arden of Faversham to similar lines and passages in the Shakespeare canon.10 Numerous editors and scholars have found these various analyses so persuasive that Shakespeare’s authorship of the work has now become the mainstream view, and in 2016 The New Oxford Shakespeare included Arden of Faversham in its collection of Shakespeare plays.

In Arden of Faversham, right after Black Will and Mosby drag Arden’s body into a side office, there is a knock at the front of the house: “Harken, they knock,” Susan says. “What, shall I let them in?”

Alice, brazen as she was, had purposefully invited guests for dinner that night, two visiting grocers from London, and was hoping to use them as an alibi. She had concocted a plan with her neighbor Greene, a man cheated out of land by Arden and a willing accomplice to the murder, to come over during dinner and claim he just saw Arden walking nearby on the former abbey grounds near the St. Valentine’s Day fair. This was now part of the Ardens’ property, but he had leased out many acres for the festivities. This is also where they intended to leave the body, suggesting some out-of-town ruffians attending the fair had committed the murder and done so while Alice and Mosby were having dinner with the two grocers and after Greene arrived. But the guests came to Arden’s house earlier than expected.

Alice immediately takes control: “Mosby, go thou and bear them company. And, Susan, fetch water and wash away this blood.”

Mosby does as told, ushering the guests into a reception room while the women try to wash away the evidence of the crime in the kitchen and parlor. But it is more difficult than expected:

“The blood cleaveth to the ground and will not out,” says Susan.

“But with my nails I’ll scrape away the blood,” says Alice. “The more I strive, the more the blood appears!”

When Mosby returns, he asks Alice if all is well. “Ay, well, if Arden were alive again,” she responds. “In vain we strive, for here his blood remains.” Alice’s inability to wash away all the blood would eventually lead to the uncovering of their crime.

The connection between this passage and the imagery and language in Macbeth is difficult to miss. Right after Macbeth stabs King Duncan in his sleep, Lady Macbeth and her husband find themselves in precisely the same situation as Alice and Mosby. Blood is everywhere, and there is a surprising knock at the door:

Lady Macbeth: Go get some water

And wash this filthy witness from your hand. …

[… Knock within.]

Macbeth: Whence is that knocking?

How is’t with me, when every noise appalls me?

What hands are here? Ha! They pluck out mine eyes.

Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood

Clean from my hand? …

[Knock within.]

Lady Macbeth: I hear a knocking

At the south entry. Retire we to our chamber.

A little water clears us of this deed.

How easy is it, then! Your constancy

Hath left you unattended.

[Knock.] Hark! more knocking. …

Macbeth: Wake Duncan with thy knocking! I would thou couldst!(2.2.50–1, 61–5, 69–73)

This, in turn, anticipates one of the most famous scenes in the canon: the walking nightmare of Lady Macbeth as she dreams about the murder and finds it impossible to wash away the imagined blood off her hands:

Out, damned spot! Out, I say! …

Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him? … What, will these hands ne’er be clean? …

Here’s the smell of the blood still. All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand (5.1.34, 38–9, 43–4, 50–2).

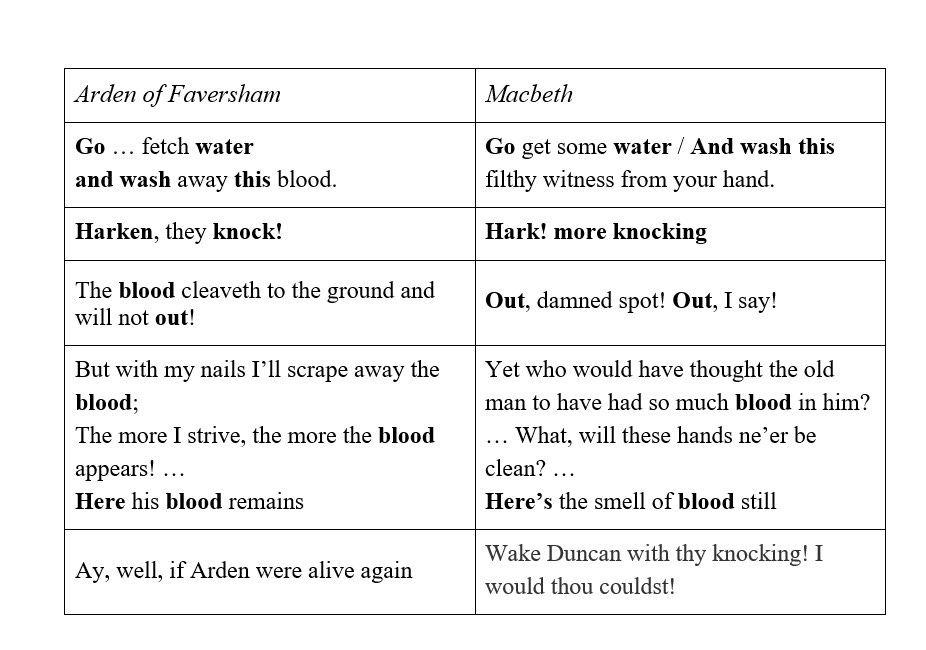

The following table lists the plot correspondences between Arden’s murder of in Arden of Faversham and Duncan’s murder in Macbeth. (Importantly, the table here is not meant to show compelling verbal parallels—but just confirm that the one murder was based on the other. For verbal parallels, see above.)

The plot parallels are numerous. Both women, fierce of temperament and masters at manipulation, have pressed their lovers into the brutal murder of an inconvenient man. Lady Macbeth has urged her husband, and Alice Arden has pushed Mosby. In each play, a knocking at the door threatens the guilty couple with possible discovery and is underscored by a similar line: Harken, they knock / Hark! more knocking. At the end of each scene, the killer wishes that the murder never happened and the victim were still alive.

But the character parallels between the femme fatales—and particularly those regarding their interactions with blood—are what is most compelling. Directly after the murder, as the visitors knock, both women bark orders to clean up the blood: “Go … fetch water and wash away this blood,” says Alice. “Go get some water / And wash this filthy witness from your hand,” says Lady Macbeth. Both women, then, with blood on their hands, suffer an attack of conscience and fear of discovery, and both cry that they cannot wash away the blood. In each case, blood becomes a supernatural accuser, refusing to disappear no matter how much the women scrub. “Here his blood remains,” laments Alice. “Here’s the smell of the blood still,” says Lady Macbeth. And the complaint that the blood “will not out!” in Arden becomes Lady Macbeth’s “Out, damned spot! Out, I say!”

Here we have our first glimpse of how North’s personal experiences shaped the canon, providing him with the subject not only of one of his first plays but also of a famous Shakespearean scene. For it is a remarkable fact that the accusatory significance of blood is actually a genuine aspect of the Arden case. It was, indeed, the very life force of Arden—his blood that Alice could not wash away—that condemned her. And the young North made sure to stress the symbolic significance of this detail in his first tragedy. Later in Arden of Faversham, when the investigators bring Alice to Arden’s body and ask her to confess, it is his blood that moves her: “The more I sound his name,” says Alice, “the more he bleeds / This blood condemns me, and in gushing forth / Speaks as it falls and asks me why I did it.” She then confesses.

Here, then, is the evolutionary history of one of the most famous scenes in the canon—Lady Macbeth’s fearful cries over her eternally bloodstained hands. And we can trace its intellectual development from a forensic fact that condemned Thomas’s half-sister, to the young playwright’s first probing of the incriminating and conscience-staining nature of blood in his dramatization of the Arden murder, to its final, accomplished realization in Lady Macbeth’s guilt-ridden lament.

Stunningly, most — yes, MOST — of Shakespeare’s renowned set-piece scenes derive from Thomas North’s life or writings. And as shown here, this includes one of the most iconic images in the history of English literature.

Coda

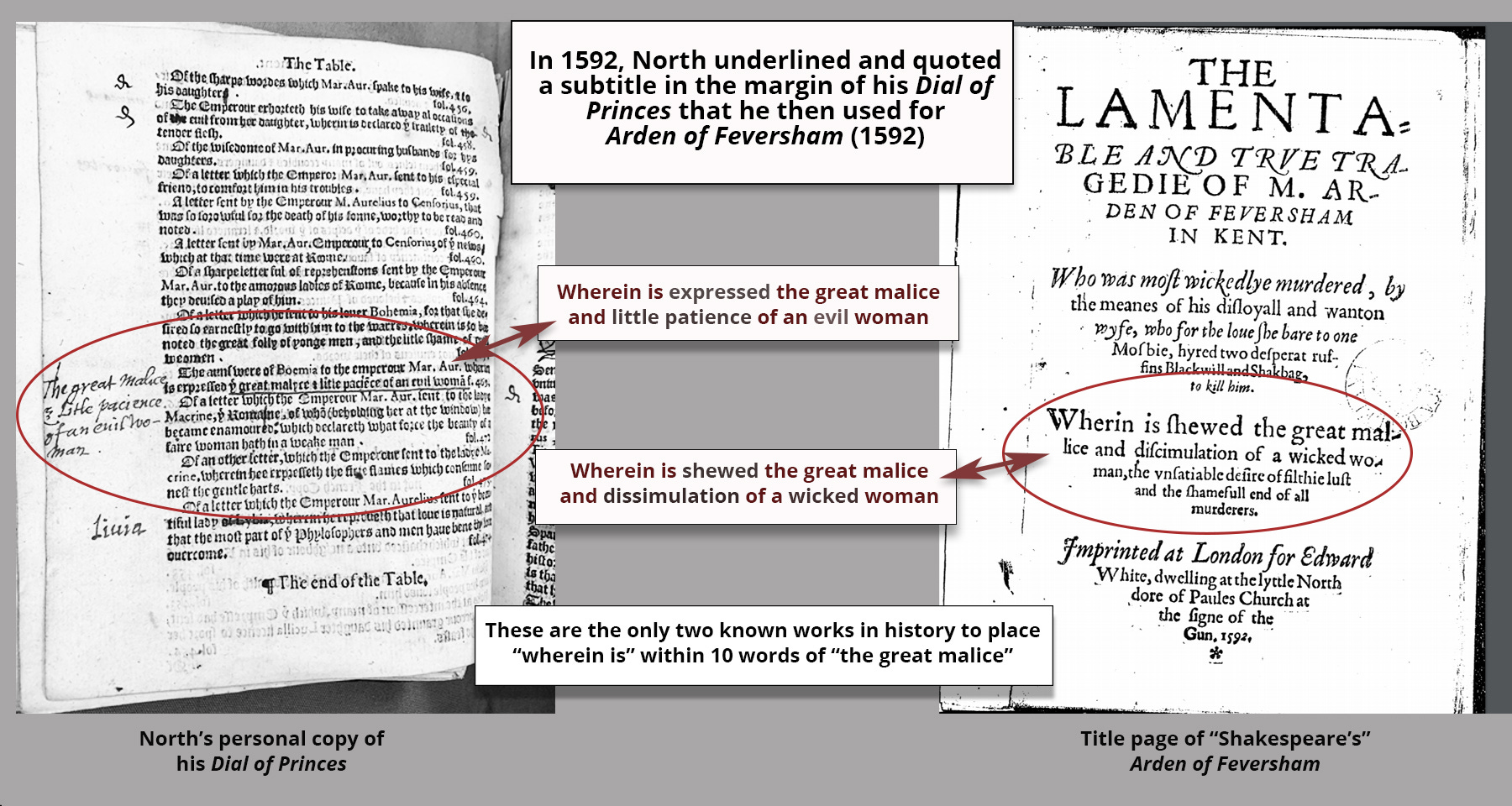

Still, the most compelling evidence that North was the author of the tragedy about his half-sister — as well as Macbeth—are the astonishing and compelling unique verbal parallels. In the Substack article here, I list more than 100 compelling parallel linking passages linking Arden of Faversham to North’s writings especially his Dial of Princes. And in the next few days, I will also publish a short video on Lady Macbeth and Alice Arden that will include a description of Thomas’s own copy of his Dial of Princes, filled with his marginal notes, that he used as a 1591-2 as a work-book for plays that he was then crafting or for the public theaters—including Macbeth and Arden of Faversham.

In the pic above, we show that, in 1592, North underlined and then wrote out a subtitle from his Dial of Princes that he then used as the subtitle for the tragedy on his half-sister, which would be published for the first time later that year:

Dial: Wherein is expressed the great malice and little patience of an evil woman (755)

Arden: Wherein is shewed the great malice and dissimulation of a wicked woman (1)

As indicated in this Google pic, no one in the searchable history of the English language has used the phrase “wherein is” within 10 words of “the great malice” except for Thomas North in his Dial of Princes (in a subtitle that he then underlined and quoted in marginal notes) and the playwright of Arden of Faversham, which is a tragedy about his half-sister’s murder of his brother-in-law with a family servant:

Importantly, it is, of course, not true that if you compare any two corpuses, you will find they uniquely share parallel lines and passages just by coincidence. Of course they will share common phrases, but they will not share unique lines and word-strings. Indeed, consider the analyses of Shakespeare’s writings made by those attempting to prove the Earl of Oxford or Francis Bacon was the secret author of the canon. They have been scouring the writings of their candidates for more than a century, searching for anything distinctively Shakespearean. But they have yet to produce a single uniquely shared Shakespearean phrase. Not one. All the verbal parallels that they have found are commonplace expressions, typically no more than two or three words in length and appearing in dozens or hundreds of other texts from the era. The same is true for another, more recent candidate, Henry Neville.

I did note above that scholars have indeed found many compelling lines and phrases linking Arden of Faversham with plays in the Shakespeare canon, but the only reason for that is that North wrote both.

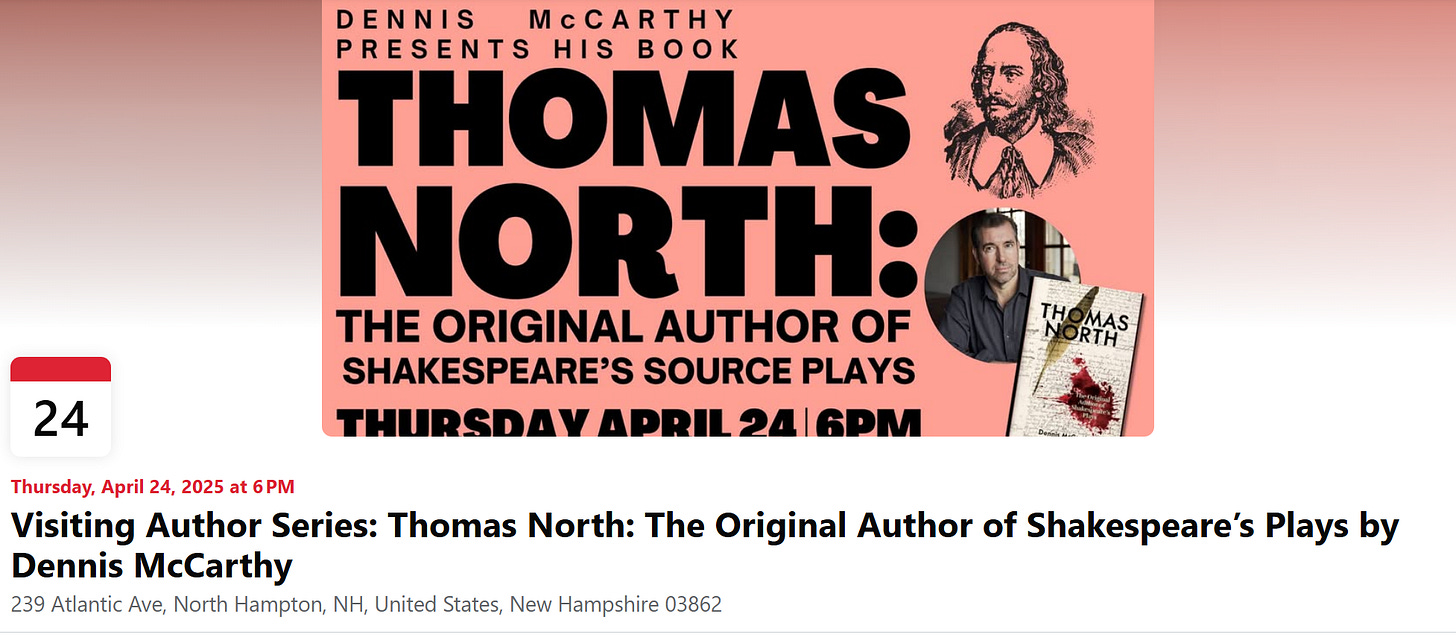

Finally, on Thursday, April 24, 6 PM, I’m going to give a brief and (hopefully) fun talk on “Thomas North: The Original Author of Shakespeare’s Plays” at North Hampton Public Library in NH. I will also be selling /signing books, and answering any questions. Also, one of the things I will discuss is the Arden murder and its use in Macbeth

John Stowe, The First Volume of the Chronicles of England Scotland and Ireland … Faithfully Gathered and Set Forth by Raphael Holinshed (London: 1577), 1703. Holinshed’s Chronicles compiled the work from many different historians—including John Stowe. And we know Stowe was the primary author for Holinshed’s account of Arden because Stowe’s manuscript notes on the murder are extant, and Holinshed’s discussion often follows these notes word for word.

Richard Helgerson, Adulterous Alliances: Home, State, and History in Early Modern European Drama and Painting (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 18.

Edward Jacob, preface to The Lamentable and True Tragedie of M. Arden, of Feversham, in Kent … (Feversham: Re-printed verbatim by J. & J. March, For Stephen Doorne …, 1770), iii–vi. See also Jacob’s History of the Town and Port of Faversham, in the County of Kent (London: J. March, 1774).

Algernon Charles Swinburne, A Study of Shakespeare (London: Chatto & Windus, 1880), 136, 141.

Sidney Lee, A Life of William Shakespeare, 2nd ed. (1898; New York: Macmillan, 1916), 140.

Marion Bodwell Smith, Marlowe’s Imagery and the Marlowe Canon (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1940), 125–8.

Bryan Aubrey, “Critical Essay on Arden of Faversham,” Drama for Students (Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2007): 24:35–8; 38.

Hardin Craig, “The Literature of the English Renaissance: 1485–1660,” A History of English Literature (New York: Collier Books, 1962), 2:82.

Arden of Feversham, rev. ed., Pseudo-Shakespearian Plays, ed. Karl Warnke and Ludwig Proescholdt (Halle: Max Niemeyer, 1888), 5:xxiv.

For a 2006 article in Shakespeare Quarterly, MacDonald P. Jackson used the Literature Online Database to uncover many Shakespearean phrases and certain literary devices, which, he believes, “overwhelmingly support” Shakespeare’s “authorship of the quarrel scene.” In 2010, he reinforced this analysis with a study of rare phrases, again concluding that Shakespeare was the author of various passages. MacDonald P. Jackson, “Shakespeare and the Quarrel Scene in Arden of Faversham,” Shakespeare Quarterly 57.3 (2006): 249–93; “Parallels and Poetry: Shakespeare, Kyd, and Arden of Faversham,” Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England 23 (2010): 17–33. In 2014, Jackson published the most comprehensive collection and proof of Shakespeare’s authorship in a full-length book on the subject: MacDonald P. Jackson, Determining the Shakespeare Canon: “Arden of Faversham” and “A Lover’s Complaint” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Arthur F. Kinney also approached the play using “computational stylistics,” concluding that “Arden of Faversham is a collaboration; Shakespeare was one of the authors; and his part is concentrated in the middle section of the play.” See Arthur F. Kinney, “Authoring Arden of Faversham,” Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship, ed. Hugh Craig and Arthur F. Kinney (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 78–99; 99.

The North connection to the Arden story is still the most persuasive piece of your authorship thesis.

Absolutely amazing! Will the Brits ever accept that a frisbee-playing Yankee solved this entire mystery?! :D